As often as not, they’ll simply call the Otago Peninsula settlement "the kāik".

That’s the Kai Tahu pronunciation of "kāinga" — which becomes kāika, in the southern dialect — combined with a dropping of the final vowel.

It’s been that way for many generations now, Ngāi Tāhu language programme Kotahi Mano Kāika kaiwhakahaere (manager) Ōtākou Rūnaka member Paulette Tamati-Elliffe says.

"It’s just that clipping of the vowel."

It’s a feature of a living language, it changes as it is used, she says.

"And it’s not just particular to Ōtākou, there are many kāik around Te Waipounamu, across the iwi — Kāi Tahu — but kāik just simply means kāika, which is a place of settlement, a home."

The earliest of these is captured in the stories of Rākaihautu, which tell of the exploration and settlement of Te Waipounamu, the history of Waitaha.

"We had these migrations down from Te Ika-a-Māui, from the North Island, but Waitaha were the first arrivals, followed closely by Kati Mamoe and then the last migrations of Kāti Kuri, Kāi Tuhaitara — who would be known as Kāi Tahu," Tamati-Elliffe says.

"And so that’s who we are today, we’re an amalgamation of all those ancient bloodlines, those whakapapa."

The kāik, Ōtākou, today is a Māori reserve, established as a place to bring together ngā mōrehu, those who had survived the challenges of the 19th century, Tamati-Elliffe says.

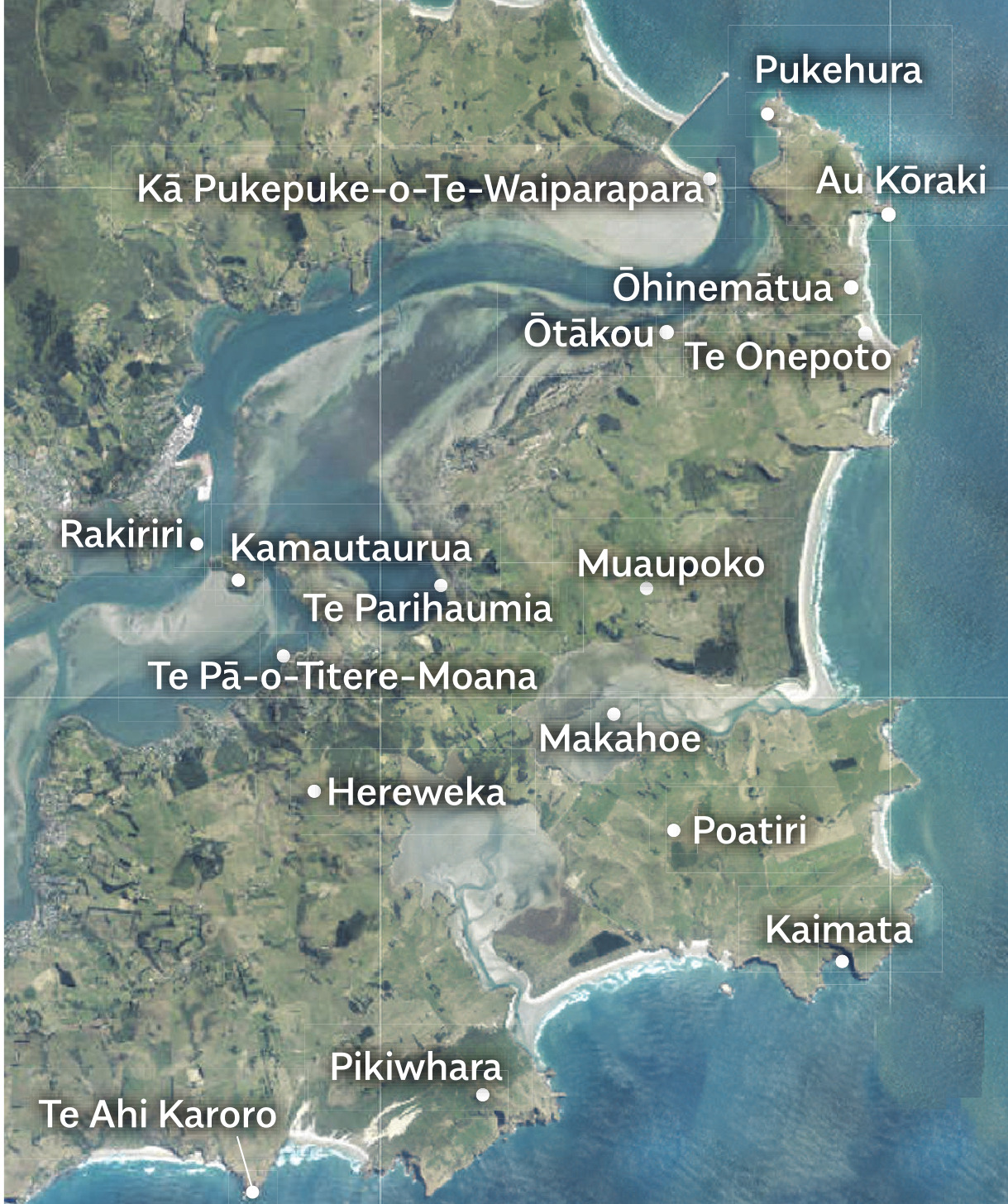

Back when it was one of many settlements, there was a village in every cove, every bay, she says. The peninsula had a lot of advantages. Kai moana and tuna, eels, were plentiful and when the peninsula was clad in native bush there would have been an abundance of manu, birds. It was a good place from which to keep watch, see who was coming and going, it was easy to defend and an easy place from which to launch waka, whether you were going north or south. And it was handy to the inland trails too.

"So, yeah, it was just nice, you know. We found the best sheltered spots, with their own microclimates, that served our people well for generations."

As such, Muaupoko, Otago Peninsula, carries a multitude of names, many intrinsically connected to the area’s history.

Tamati-Elliffe, who is also a member of the New Zealand Geographic Board, issues a note of caution about that one though, Muaupoko. It’s the subject of ongoing research as the sources for it are principally European, and transcriptions of Māori by early Europeans have been known to carry errors, unaccustomed as the Pākehā ear was to the pronunciation of te reo.

As Kā Huru Manu, the online Ngāi Tahu Atlas tells the story, Muaupoko was created by the demi-god Tū-te-rakiwhanoa.

When Aoraki and his three brothers — Rakirua, Rakiroa and Rarakiroa — arrived from the heavens to visit Papatūānuku, their return voyage went drastically wrong, the waka crashing into the ocean, forming what would later be known as the South Island (its earliest name was "Te Waka o Aoraki"). Aoraki and his brothers climbed to the highest side of the waka, where they turned into mountains. When Tū-te-rakiwhanoa discovered the wrecked waka, he decided to reshape it for human habitation, carving out many of the island’s geographical features, including Muaupoko.

Another name with ancient origins is Pukekura, now more commonly known as Taiaroa Head — renamed for Te Mātenga Taiaroa, a rangatira who, among other things, helped to see off the southern raids of Te Rauparaha and Ngāti Toa.

However, the original name, Pukekura, is linked by waiata to the traditions of Māui, Tamati-Elliffe says.

Other names on the peninsula have more recent origins, the detail of which remains well known.

Harbour Cone, Hereweka, is one.

Paulette Tamati-Elliffe’s son Tumai Cassidy takes up the story, which revolves around a warrior of legendary status, called Tarewai — but starts with another, Waitai, the first of Ngāi Tahu’s ancestors to reach Otago.

Waitai had ventured south from Kaikōura with a party of warriors.

"He was upset with his relations so he decided to take his anger out by raising a party of warriors and heading south and fighting anyone and everyone who came across their path."

He ultimately ended up in Te Rua o te Moko, Southland, where he fought with Kati Mamoe and was killed, Cassidy says.

Just four people survived from his party, two staying down south and two returning to Kaikōura.

"Waitai was a pretty important ancestor, he set up the pa of Pukekura, as he was moving south, and so there were people still there living at that pa when he was killed."

When word reached Kaikōura that Waitai had died, his nephew Te Ruahikihiki, a leading Ngāi Tahu chief at that time, called for a warrior to revenge his uncle’s death.

"According to our history, Tarewai was eight feet tall, muscley as, and he had with him a patu, war club, called Kakoauau."

When Tarewai arrived at the peninsula, he first met with his relations at the Ngāi Tahu pa, which was just a stone’s throw away from a Kati Mamoe pa.

"Kati Mamoe saw this massive warrior arrive and they thought ‘there’s no way that we’re going to be able to beat this fella in combat’. So they had to come up with a different way to try to defeat him and his warriors."

Their strategy was to call for an end to the conflict between the two tribes, to stop fighting each other and settle the peace. One way of doing that in those times was for the people to come together to build a whare, build a house.

So, the two tribes, Ngāi Tahu and Kati Mamoe decided they’d build a house near The Pyramids, in Ōkia

"On their smoko they decided to see who was the strongest of the two tribes. And so they start to wrestle, the warriors start to wrestle, one on one."

But as they wrestled, a Kati Mamoe warrior would drag a Ngāi Tahu warrior behind a flax bush where four of his mates were waiting, and they would take them out.

"All of Tarewai’s warriors were taken out one by one and Tarewai was left, last man standing."

According to the legend, he was pinned to the ground with two men on each arm and two men on each leg. Then they used his own patu to begin to slice his stomach open, from the chest down.

Fortunately for Tarewai, at that time there was a party of people travelling across the hills and and they called out to the Kati Mamoe warriors, which distracted them for a second and that’s when Tarewai leaped up, ran across the beach and jumped into Makahoe, or Papanui inlet as it is known today.

"He swims up Papanui inlet and he reaches a mountain, he climbs up to the top of that mountain and there was a cave, which used to be on that mountain.

"When he was in that cave he took from his belt a piece of harakeke and he made a snare and he caught a bird known as the weka, caught it and he was able to snare it and so he used the fat or collected the fat of the weka and he lit a fire and heated up some rocks. And so he used the fat of the weka and these glowing hot rocks to seal, cauterise his stomach back together."

As he was doing that, the patupaiarehe — the fairy guardians of the forest — helped to heal him in the night.

"And so that mountain from that day on was known as Hereweka, which means to snare weka — which is related to the story of Tarewai."

Having recovered, Tarewai wanted to be reunited with his mere, his patu, Kakoauau.

"So, he goes down to the Kati Mamoe village in the night, takes out one of the guards, goes and sits down by the fire and everyone’s eyes are blinded by the light of the fire and they don’t recognise who he is.

"So, he asks about the patu of the warrior Tarewai and one of the men brings it out, it goes around the circle, around the fire, gets into his hands and then he leaps up and he says, ‘Nāia te toa o Tarewai, kei a ia anō tōna patu’. Here is the brave warrior Tarewai, I have reclaimed my patu."

He quickly accounts for the warriors seated around the fire but is chased by others back to Pukekura, across Taki Haruru, the beach below the heads.

The tale of Hereweka is typical of the way in which the land was populated with names, to recall events or describe features, Cassidy says.

"There is lots and lots of knowledge that is stored within a placename. It gives you an insight into what those landscapes looked like, who was living there in those places, and for us it is our connection to our ancestors."

There are stories that stretches back 40 generations, he says.

And because places are named for ancestors, when those names are corrupted it does not sit well with mana whenua.

"We would not trample upon the names of others in that way."

Tamati-Elliffe agrees.

"Those names ground us in who we are, in our identity, they remind us of our ancestors of the past. It’s all about whakapapa for us, so it is not just a place name it’s a beacon, it’s a marker of identity. It connects us to our past."

As a result of that close connection with the whenua, there is a sense of grieving for the modification of landscapes that has not served us well as humans, she says.

But current generations are much more aware of the changes that are happening and want to reconnect and restore that symbiotic relationship with our taiao, with our environment, she says.

"It may just be a place name to somebody but for us it is whakapapa, it is connection. To be able to have those acknowledged and to have them resounding again on the lips of our people, is so important for us and our identity and our wellbeing."