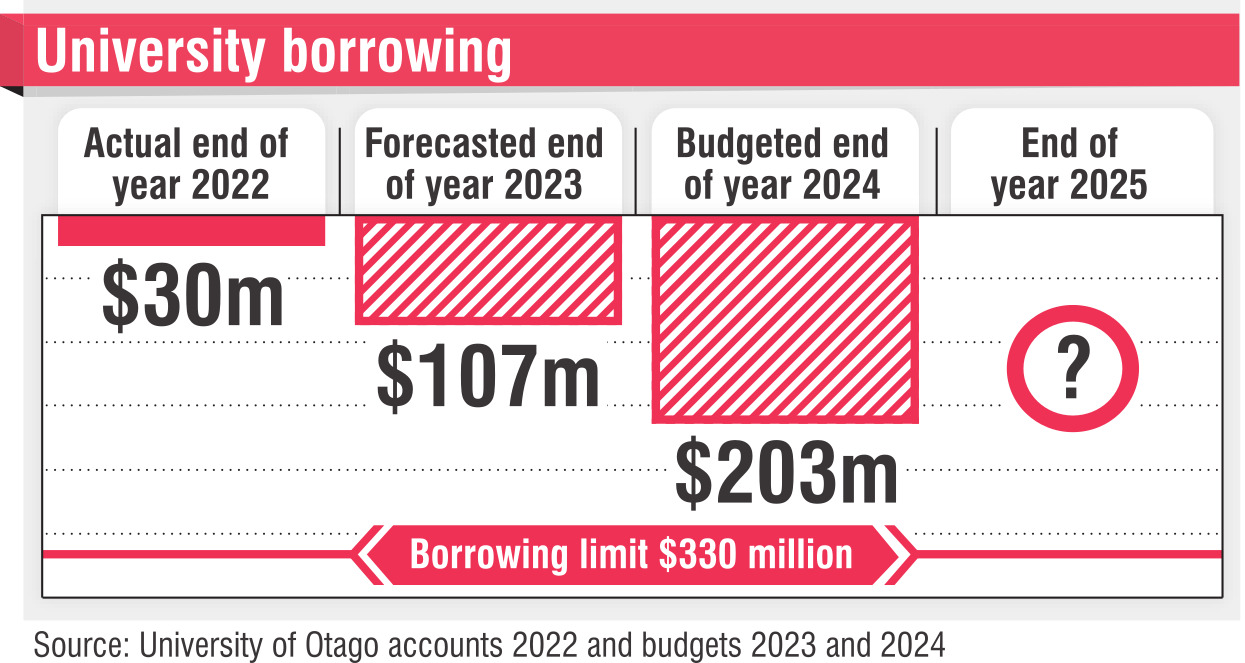

An analysis of the university’s finances in today’s Otago Daily Times reveals the university’s debt limit is looming into view as it borrows hundreds of millions for building works and incurs runaway operating expenditure, well above income.

When asked what kind of financial management legacy she would leave the next vice-chancellor, who is being appointed, acting vice-chancellor Prof Helen Nicholson told the ODT "I moved quickly and decisively to address the financial issues before us".

"My aim has been to stabilise the situation and make the key changes required so that the new vice-chancellor can take up the reins with the vast majority of that work already done."

She announced in April last year a plan to shave $60 million permanently off the university’s operating budget deficit to break even last year, but said it could not be done within 2023.

It would be pieced together from permanent savings made over a longer period and include significant staff cuts.

However, ODT analysis reveals much of the savings achieved last year and planned for this year are not the permanent savings Prof Nicholson is seeking.

Temporary savings include asset sales, reducing scholarships and not filling vacant positions for a while.

Without planned savings that sit in this year’s operating budget, the gap between expenditure and income is even bigger than last year — $63m to breakeven, and about $86m to turn the level of surplus advised by the Tertiary Education Commission.

It would have nearly topped $100m if the government had not provided a $10.5m bailout.

The university is planning to fill only about half the shortfall required to breakeven. It plans to end this year with a $28.9m deficit, predicated on achieving savings of nearly $35m within the year, from asset sales and a savings target.

Running costs are higher than income and increasing faster. Staff costs alone are expected to rise by more than $16m this year, dwarfing the savings achieved by last year’s voluntary redundancies, which are only expected to save $9m this year.

A well-informed source who wished to remain anonymous said "things are getting worse — the cuts would have needed to be deeper in the first instance to have impact and help the long-term viability of the university".

It is planning a further $178.6m expenditure on capital expenditure in 2025, likely requiring further borrowing.

Its borrowing limit is $330m plus a further $70m that it has agreed, with the Tertiary Education Commission, to hold back for liquidity reasons.

When asked about the risk of the university hitting $330m borrowing and having to dip into its last-ditch $70m, Prof Nicholson said "I am comfortable this risk is being appropriately managed".

The university had "headroom" because of the additional $70m and had "a significant ability to slow capital expenditure if required".

The university had also considered, in its planning, "a raft of factors" that had changed, including the $10.5m bailout by the government, the trajectory of international enrolment recovery and high levels of success in some grant bid rounds.

It was "changing tactics, not strategy", to drive towards its original goal of a $60m permanent saving to its bottom line, which it still hoped would be achieved by next year, along with a break even position and the promise of a surplus in 2026, she said.

Some borrowing is also planned to be paid off through a depreciation line on the operating budget.

Its fall into troubled waters was because of "no long-term forewarning of the particular combination of pressures that led to a financial situation of the magnitude we have faced", she said.

She blamed higher inflation which had "caught out ... organisations in many sectors".

"It was the impact of this that generated a situation of the magnitude we faced at the start of the year."