Illustration was the first way to render clothing in artworks, advertising and publication before the rise of fashion photography and a focus on the new took hold in the 1950s and 1960s. In the early 20th century, fashion illustration was key to the fashion press: inspirational and evocative at the same time, the medium walked the fine line between design and art. By the mid-20th century however, fashion photography had become the dominant medium.

Fashion photography met the needs of a brand’s marketing department, and photographic editorials appealed to consumers as photographers could take an image and have it quickly available to the public. With the arrival of social media — and the smartphone — images from fashion shows were appearing instantly. Paradoxically, this has helped revive fashion and dress illustration, as drawn images show different artistic expressions. In a world of continuous scrolling through photographs, illustrations stand out as a striking alternative.

Before fashion photography took over, fashion and dress illustration was an art form. While portraiture often rendered people in their finest garments, artists such as Georges Barbier, Erte, Rene Gruau and Barbara Hulanicki focused instead on dress and clothing, showing fine details, drapery and decoration.

Fashion design can also double as fashion illustration, with designers’ sketches showing not only the design idea, but detail, colour and garment movement and draping.

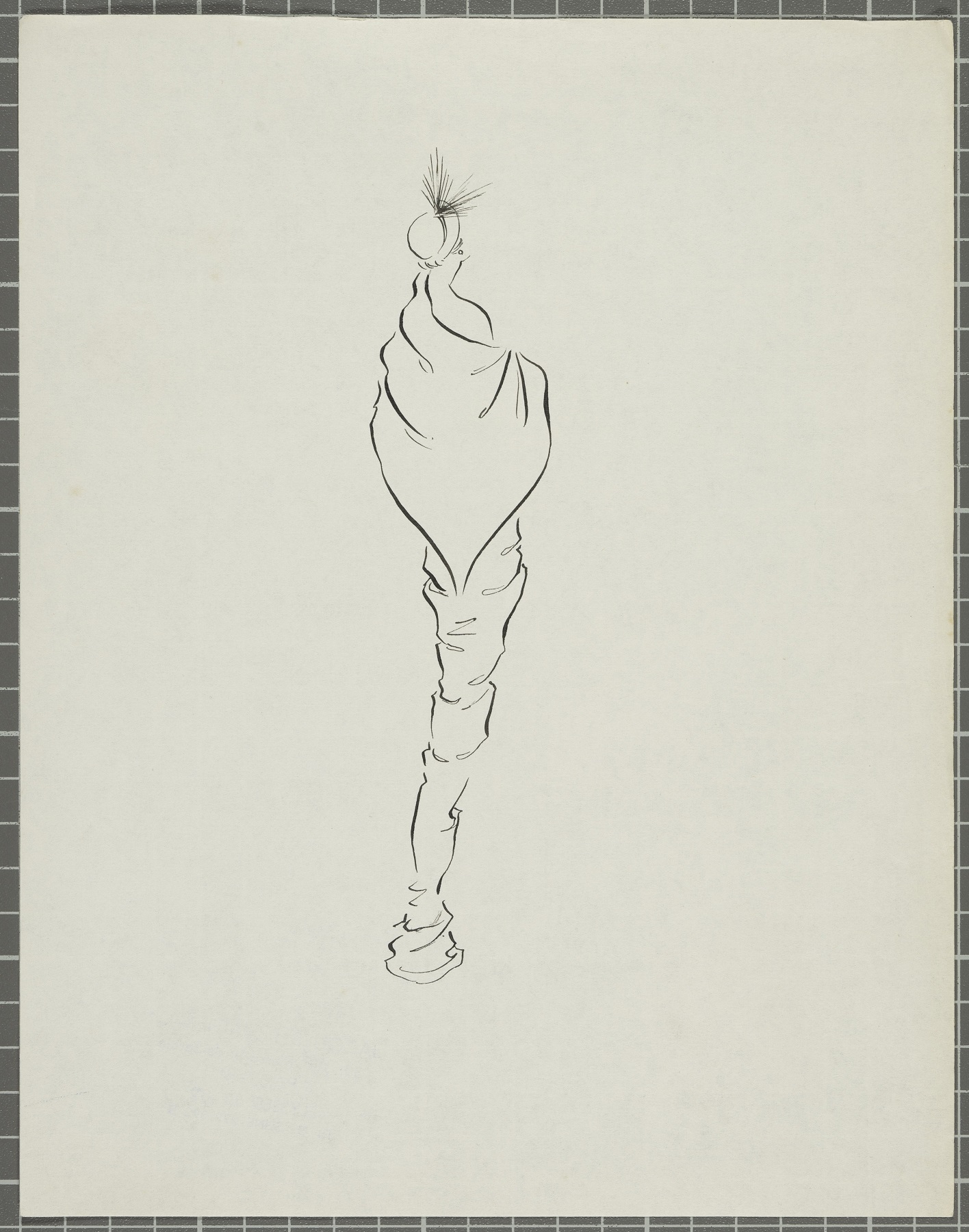

Some, however, use minimal detail with only outlines to suggest a garment. Design illustrations like this are held at Hocken Collections, in the records of Avice Bowbyes (1901-1992), former head of the University of Otago’s clothing department in the faculty of home science between 1929-1961.

During her second sabbatical to the L’Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisenne (a couture "school" in Paris) in the mid-1950s, she acquired a press pass to view French designers’ new collections. Bowbyes’ papers include invitations from these shows, as well as photographs and line drawings of different garments from both the Jacques Fath and Schiaparelli collections.

The line drawings have a dramatic flair that is not captured in photographic images. In particular, the Fath drawings are simple and show only the dress silhouette in minimal lines, but also look complete. The illustrations are not detailed, but the viewer can imagine what finished garments would look like.

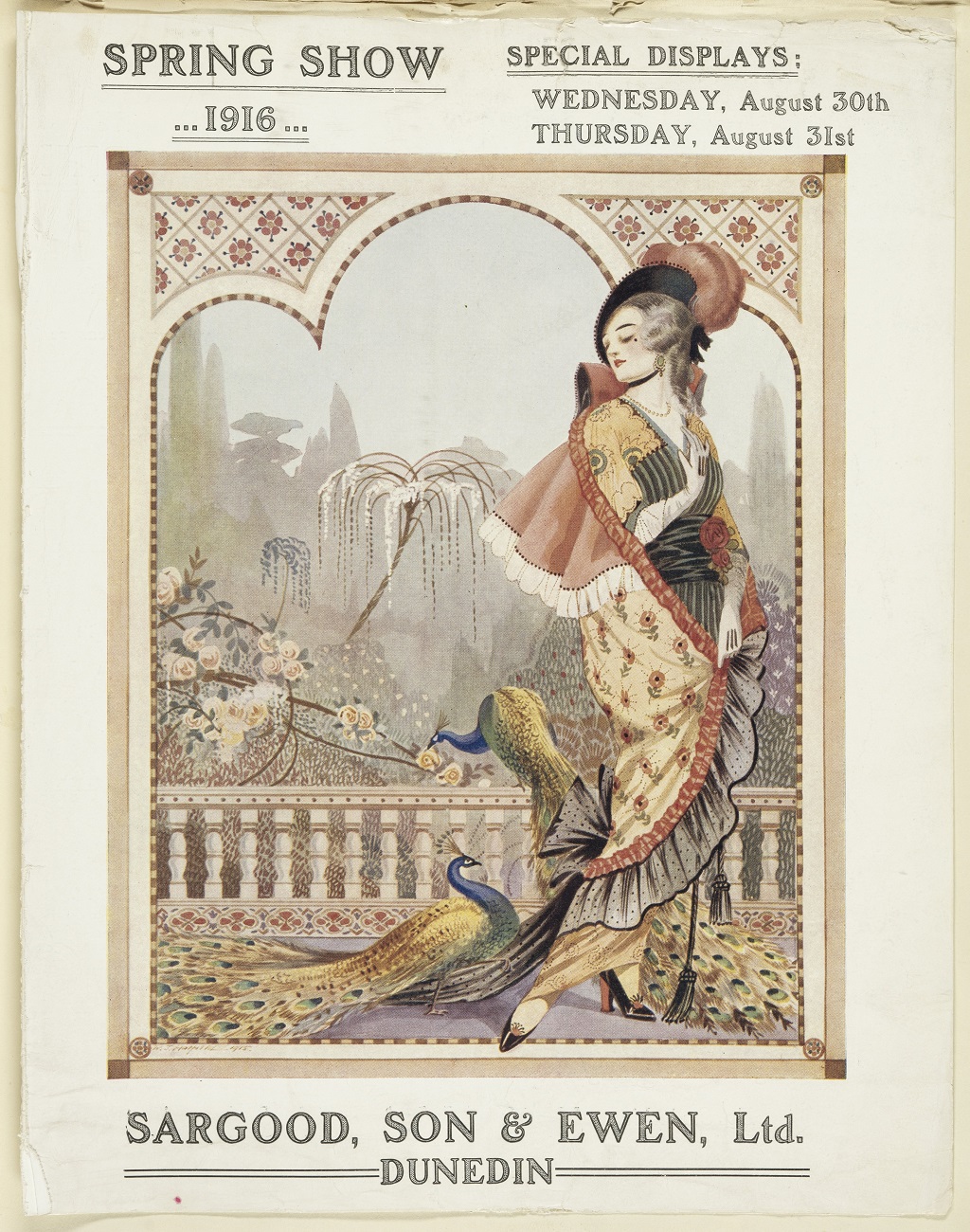

Retailers used illustrations to advertise merchandise in print. Smaller stores used external advertising agencies and art departments, but larger stores had internal advertising departments with full-time commercial artists or copywriters. Companies such as Sargood, Son & Ewen (local manufacturers of clothing and footwear between 1861-1873) used illustration to advertise fashion and dress on a number of their brochures, cards and company invitations to fashion shows. The records of Sargood, Son & Ewen held in Hocken’s archives provide evidence of these advertisements and invitations showcasing textiles, apparel, shoes and accessories.

In contrast to the Fath design illustration, the brochures of fashion shows for 1915 and 1916 feature fully coloured, detailed illustrations of women wearing decorative gowns in the contemporary fashion. The 1916 Spring Show brochure is especially striking. The illustrated garment is highly detailed down to the floral pattern and trim on the cape, the contrasting pattern on the dress itself, the plumage on the hat and the heeled shoes.

Sharing the foreground are two peacocks, their colourful plumage surrounding and merging with the gown.

These and further examples of fashion and dress illustration are available for viewing at Hocken Collections.

To visit

- Hocken Collections is open Tuesday-Saturday, 10am-5pm. Public stack tours are available on Thursday mornings at 11am. Inquiries (03)479-8868 or www.otago.ac.nz/library/hocken

Amanda Mills is Hocken liaison librarian and curator of music and AV collections.