"He didn’t talk about it," Matthias says.

But Luafutu did begin to tell his story in a book he wrote while in Rolleston prison. Matthias gave that book A Boy Called Broke to his theatre teacher Tom McCrory 20 years ago when he dropped out of Toi Whakaari New Zealand Drama School as an explanation for his decision.

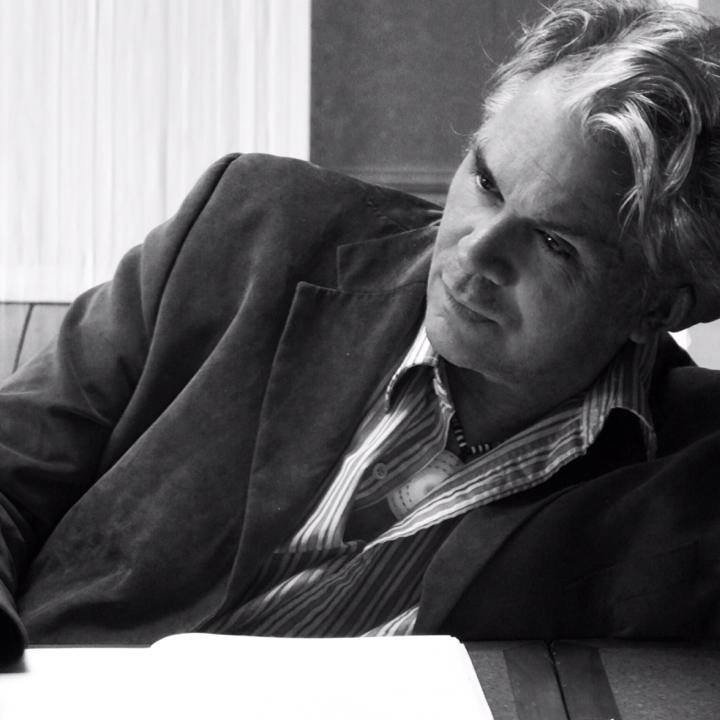

"It was a blow that he decided to leave," says McCrory. "He was a remarkably talented actor."

Years later McCrory, who always had a sense of unfinished business about that experience, got the book off his shelf and re-read it.

"I thought ‘wow, there is an incredible story in this book’."

He got in touch with Matthias about using it as the basis of a production for his and wife, director Nina Nawalowalo’s Conch Theatre Company — the result was The White Guitar. It featured Luafutu and his two sons Matthias and Malo (otherwise known as rapper Scribe) telling the family’s story of immigrating to New Zealand for a better life and the reality of hardship and loss through violence, drug addiction, prison and gangs.

"It was a landmark production in New Zealand theatre, telling three men’s intergenerational story from 1958 when his father arrived from Samoa to the 2011 earthquakes in Christchurch," McCrory says.

A small part of the play told of Luafutu’s time as a State ward in a boys home. He was 11 when he was sent to Owairaka Boys home and later to Kohitere, a boys training centre that was one of the main subjects of the recent Royal Commission of Inquiry into abuse in state care.

That story has been expanded to become the basis for A Boy Called Piano after McCrory and Nawalowalo, who before the Royal Commission, were struck by the injustice and lack of voice many survivors of abuse in state care had and wanted to do something to contribute to the conversation they believed the nation needed to have.

"Our medium is theatre. We didn’t know what would come from it, we just had this sense that it was a very important story that needed to be told."

"For him to make the journey is an extreme act of courage. As we learnt with White Guitar, placing the story in the public eye has all sorts of consequences, some we can predict, some we cannot.

"Fa’amoana has incredible courage, had a sense for some reason he had lived to tell tale but many of his friends not lived to tell tale, they had died living a life of hurt and suffering or are serving long sentences in prison."

Luafutu and McCrory collaborated on the script to A Boy Called Piano. Based in Auckland in 1963 it tells the story of three 11-year-old boys meeting in the cells of Family Court. Two are Maori, one is Samoan — Wheels, Piwi and a boy called Piano. They are made wards of the state and taken to Owairaka Boys Home and it tells of their experiences during the next few months.

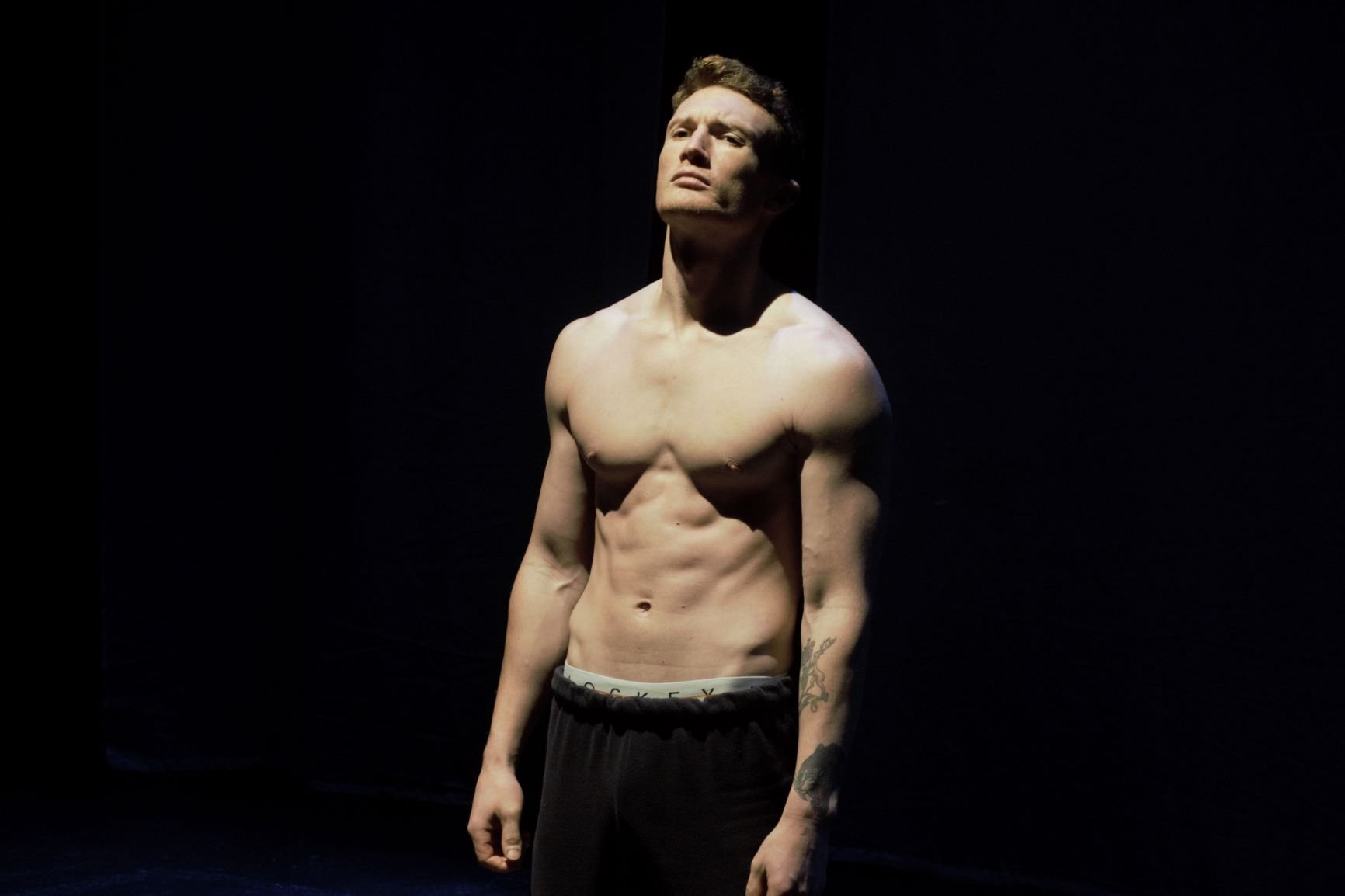

In this play, as well as Matthias and his father are Aaron McGregor, Rob Ringiao-Lloyd and returning to the stage Ole Maiava.

"It is a combination, a very physical style of storytelling. The actors play multiple characters. The real focus is about the light rather [than the] darkness, the connection of three boys through culture, through language, through music. It’s how these boys survive and their relationship which in real life lasted until death."

Working so closely with their family and putting its story out in such a public domain has not always been easy.

Matthias’ father had not talked about his time as a state ward and the only things Matthias knew of those institutions was what he heard from older inmates while in prison himself.

In 2019 Conch held a development season at BATS Theatre in Wellington and with funding from Performing Arts New Zealand (PANZ) was about to hit the road on a national tour when the Covid-19 pandemic hit cancelling the tour.

To keep those involved in employment Nawalowalo "side-stepped", and with the support of PANZ, the team involved adapted the play for radio and recorded it in partnership with Radio New Zealand.

By this time she also knew she also wanted to make a short film about Luafutu’s journey but it soon became apparent that it had the potential to be a full-length documentary if they could secure funding. Earlier members of the Royal Commission of Inquiry had seen the play and were "incredibly moved by it". Struggling to get Maori and Pasifika peoples to come forward to the tribunal they were keen to partner with Conch.

This allowed Nawalowalo to be able to mix interviews, dramatised scenes and underwater imagery into a documentary seen in New Zealand recently at the New Zealand International Film Festival. It also won an award at the Montreal Film Festival.

With Covid now retreating PANZ has again agreed to fund a national tour of the play bringing the team back together again. Parts of the documentary have been woven into the play to complement the performance of the actors and live music by pianist Mark Vanilau (Dave Dobbyn’s pianist for many years) who plays a baby grand on stage.

For McCrory the piano is another character in the play often expressing the "voice" of the mother.

"The play starts with "the first time I heard the piano I was still in the womb, my mother plays in church", the voice of the piano is the first thing we hear in the play. The sound effects come from the piano. It is [a] character in [that] it comes and speaks to the children," McCrory says.

"As an actor, it is so soulful, his music we work off it. It is one of my favourite characters in play."

Matthias says initially working on the plays was quite hard especially as it forced him to look at things from his father’s point of view.

"Dad says arts are a way of release. With each performance we are able to bring up things and being in a safe environment are able to leave it there on stage. So it’s not so much hard anymore."

The social justice elements of the plays are what drew Matthias back to the stage, something he has wanted to do for some time.

"Anything else wasn’t singing out to me, this kind of work, social change I’d do it for anyone, the story just happens to be my fathers, it’s brought us closer as a family."

It has also dawned on him, even more so after the documentary, how precious the time has been for his family and the Conch team.

He now realised what his father had been living with for so many years.

"It’s been enlightening to understand it. In my dad I see a different man, our relationship is totally different, it’s beautiful. Forgiveness has been a big part of it. I haven’t been the perfect son so I had to ask forgiveness too."

"Watching him in his winter years have some summer days has made it easier for me."

The show is coming to Dunedin as part of the ODT Dunedin Arts Festival and it is the first time Conch has presented one of its works in the South Island.

"We’re very excited to share our work and connect with [the] dunedin community," McCrory says.

They will hold a question and answer session after the show so the audience can share their thoughts and experiences if they wish.

"That desire and need of audience to share, is what I love about the piece. There’s something about listening to someone else’s story that makes you feel very deeply about your own. It’s not just Maori and Pasifika, it’s about family, about children, survival, about our history as a country.

These hurts must be faced, whether it’s personal history or national history, it is no good for anyone to avoid. The purpose of telling this story is about healing."

To see:

A Boy Called Piano, Regent Theatre October 13 and Oamaru Opera House, October 15, part of the ODT Dunedin Arts Festival.