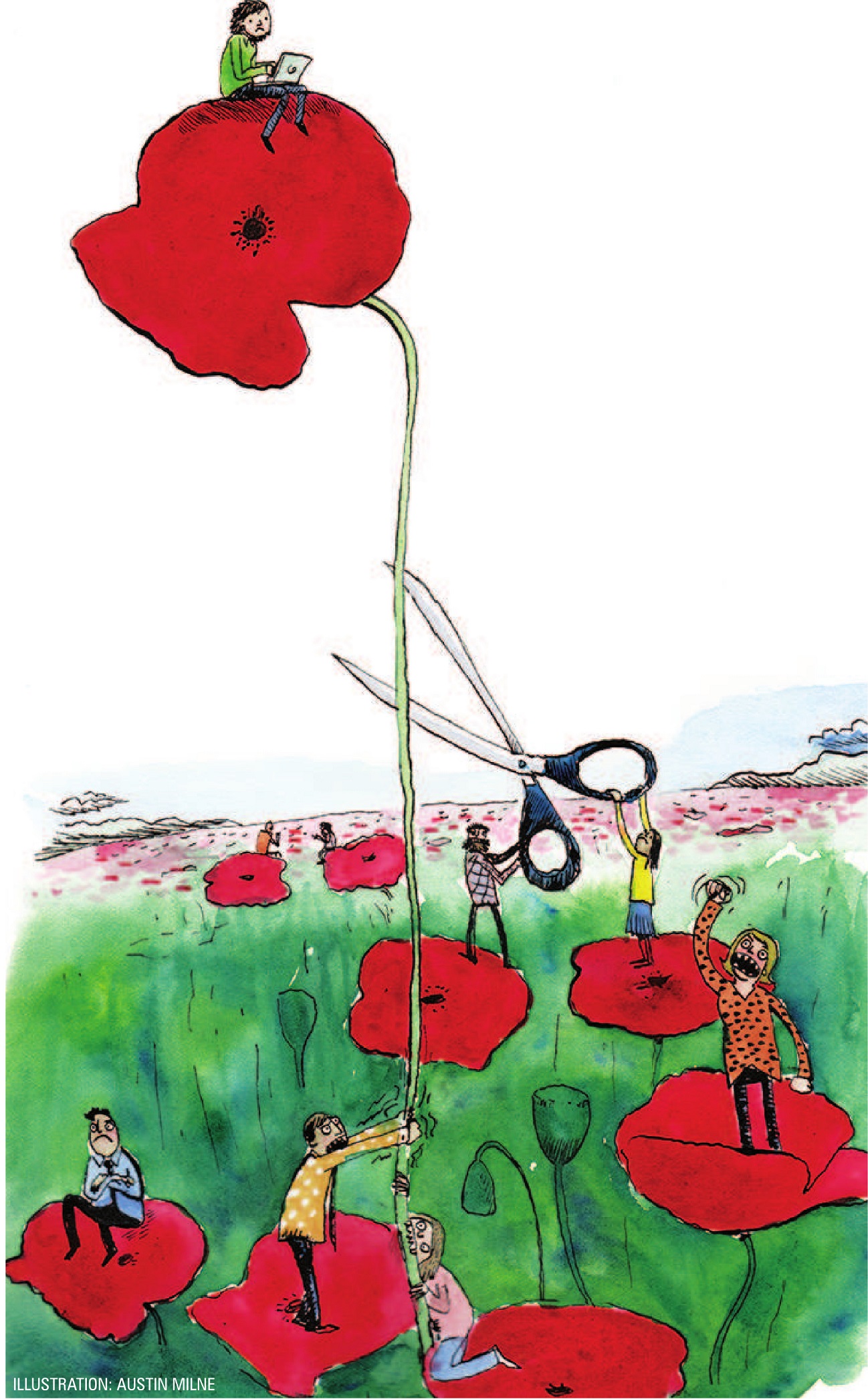

Tall Poppy Syndrome (TPS) is a phenomenon synonymous with New Zealand’s culture.

That tendency to begrudge, resent or mock people of success, talent or status, or play down one’s own achievements, went back to the country’s egalitarianism — or "don’t stand out from the crowd", as Dunedin academic Jo Kirkwood says.

She first became fascinated with the topic while completing her PhD around motivations for becoming an entrepreneur.

TPS unexpectedly kept cropping up during interviews and it led to her undertaking research on it, focused on the experience of entrepreneurs in New Zealand.

The findings, back in 2015, showed many entrepreneurs experienced TPS to the point that it impacted how they ran their businesses and affected them personally.

Now Prof Kirkwood, from Otago Polytechnic, and Rod McNaughton, from the University of Auckland, have completed another study on TPS and the severity of the responses — which even included death threats — have taken her by surprise.

The drive for this year’s survey was two-fold; at the end of 2021, the TPS debate intensified following the tragic death of a young entrepreneur.

The Government also urged Kiwis to "be kind" in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, yet many could not return home due to the quarantine system, setting up a "them and us" scenario which some commentators interpreted as TPS, the report said.

The pair wanted to understand more about how people experienced TPS and uncover what, if anything, could be done about it.

There had been limited research on the topic in New Zealand to date and it could not be estimated how widespread it was.

There were 297 respondents, ranging in age from 18 to over 65, and 76% were women. They were primarily employees (46%), entrepreneur/business owners (21%) and contractor/sole traders (15%).

Ninety percent of respondents believed TPS existed, which was not surprising given people self-selected for the study, and that figure was probably higher than it would be in a representative sample, Prof Kirkwood said.

There were comments of TPS impacting self-confidence and increasing self-doubt, adverse effects on mental health, feelings of deflation, isolation, anxiety, stress, depression and even suicidal thoughts.

For some participants, the impact caused them to disengage, feeling that withdrawal was the only option, or stepping out of the public eye.

Others wrote of lost opportunities, limited sharing and celebrating their success, or facing negativity.

Some accepted TPS as being present in New Zealand and used it as motivation to succeed even further.

Many participants wrote about the perception of success in New Zealand being more negative than positive.

That theme included observations that success was seen as unfavourable, has a stigma and was not encouraged.

What also worried Prof Kirkwood was that people were "opting out".

"People in a really great position to be role models and be able to help people, give them a hand up, are going to say ‘why would you?"’ she said.

There were several examples where people felt they could not call it out, due to power dynamics, so they left their jobs. That was a massive loss, she said.

In more than 40% of cases, respondents experienced TPS through in-person conversations, with social media a distant second. The perpetrators were colleagues, followed by people who did not know them and friends.

That, for Prof Kirkwood, was one of the biggest surprises — "it’s right on your doorstep" — rather than from the so-called faceless keyboard warriors on social media.

But that, she believed, offered an opportunity to address the issue; the ability to have a conversation with the perpetrators about the journey to success — the highs and lows, lessons and failures.

More than half of the respondents who believed TPS existed also believed it could be reduced. They believed progress could be made in three main areas — societal change was needed, education was key, and all types of success should be celebrated.

Some participants felt TPS should be acknowledged as existing in New Zealand and should be "called out" when observed, while some thought it should accepted as part of New Zealand’s culture and work around it. Others wrote about using it as motivation to continue striving for success.

While the culture around TPS could not be changed overnight, Prof Kirkwood said there were some things that could be done to change the conversation to a more positive one.

As hard as it was to change the conversation, it needed to happen at grassroots level and such behaviour needed to be called out.

Individuals needed to look at what they could do; it was about helping each other and celebrating even small successes.

While there were only so many people who could become All Blacks or Black Ferns, go to the Olympics or become astronauts or Prime Ministers, the report said many successes were not limited to a select few, and the "success pie" could be grown.

"There are fewer limits on how many people can succeed if we take a comprehensive view of success and focus on each individual’s definition of success.

"One person being successful does not necessarily mean another fails. For example, in applying for a job, one person might feel success by getting an interview, and another when they were offered the position."

Prof Kirkwood said there were a few people doing work in the TPS area; social development programme E Tu Tangata was doing good work tackling the topic in schools.

She believed there now needed to be a large study to identify if TPS was widespread across New Zealand. It should represent the population in terms of gender and ethnicity.