Tayla Mokotupu sticks close, holding Shelley Harris’ hand tight, a shy smile playing across her young face as she listens to Mum’s words.

In front of the pair is Halfway Bush School’s vegetable garden. Three large planter boxes overflowing with herbs, silverbeet, lettuce, potatoes, edible flowers ... and rhubarb, lots of rhubarb.

Mother and daughter are here at the Dunedin hill-suburb school to have their photographs taken. And to take home a basket of soil-grown, leafy produce — the makings of a tasty, nutritious meal.

Harris is talking about the cost of buying groceries.

She does not consider her family is badly off. But she has certainly noticed the price of most items going up at supermarkets.

"Definitely. Bread, milk ... everything," Harris says.

"And to be honest, I think we’re getting less for more. A loaf of bread seems smaller these days."

She knows "a lot of people" who are having trouble making ends meet, including her adult daughter and her grandchild.

"They’re struggling to afford rent and food."

It is not right, Harris says.

She has heard of the Commerce Commission’s inquiry into New Zealand’s supermarket system, particularly its report of million-dollar-a-day profits, and feels strongly that something is wrong.

"I think it’s disgusting. There are people that we’ve helped because they can’t make ends meet. The profits should be going to help those who are struggling."

The signs our food system is broken are all around us.

The Commerce Commission’s final report into New Zealand’s $22 billion supermarket industry, the heart of this country’s food system, found plenty wrong.

Exemplifying that finding, an Otago woman has reported slashing 35% off her grocery bill by ordering groceries online from Australia.

Many considered the commission’s recommendations on changes to the sector sadly limp.

National Maori Authority chair Matthew Tukaki was typical, calling the recommendations "disappointing". Tukaki had wanted the commission to consider the forced sale of the big players’ smaller stores, Four Square and Fresh Choice, to prise open the door for a new contender.

Instead, the report called for a mandatory code of conduct for the sector.

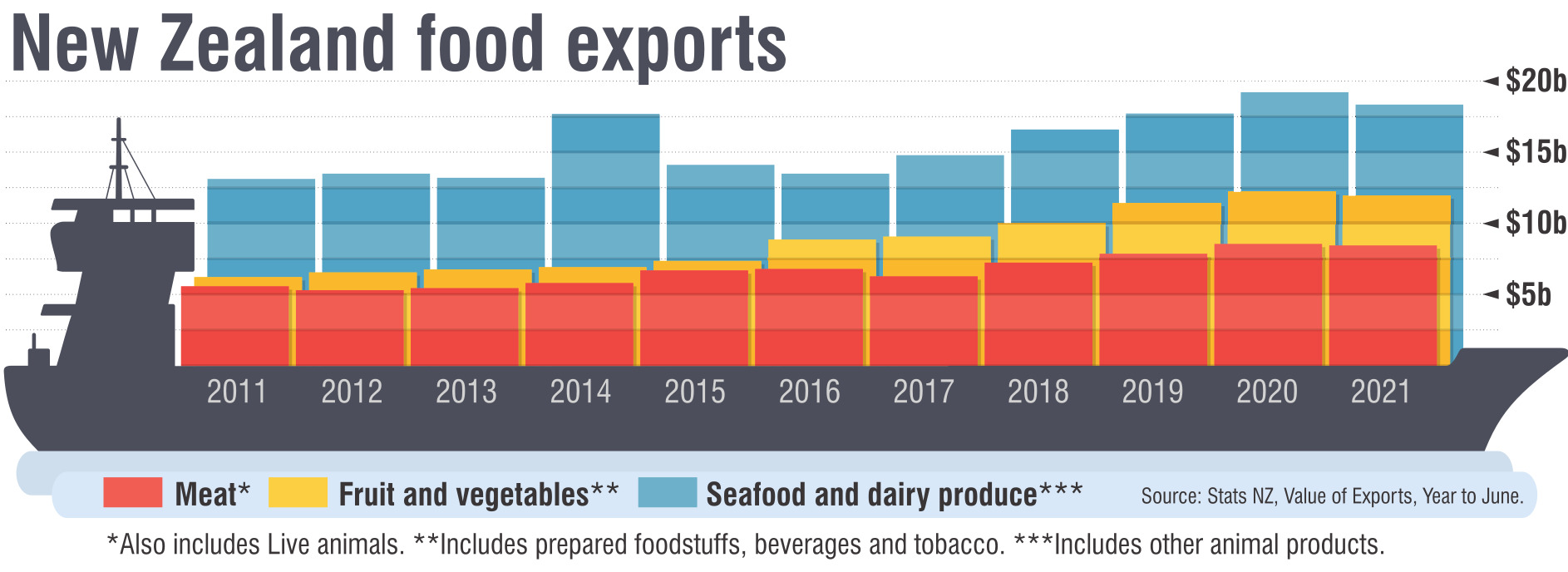

This at a time when the highest annual food price increase in a decade, 7.6%, has only added to what is fast becoming a cost of living crisis. Fruit and vegetable prices have gone up 18% during the past year. The country’s foodbanks are reporting unprecedented demand, in some cases 300% up on a year ago, including many more clients from home-owning households with two incomes struggling to pay mortgages and buy food.

"They're just completely unable to deal with the scale of the need that's out there," Prof Hugh Campbell says of the food banks.

"The rise of food banks is an awful thing to witness in a country which is such an abundant food producer," the University of Otago sociologist specialising in food and agriculture says.

The impact of our faltering food system is also evident in our health and our environment, Prof Alan Renwick, of Lincoln University, says.

"We have the third highest adult obesity rate in the OECD, at an estimated cost of $2billion in healthcare services each year," Prof Renwick, an agricultural economist, says.

"Our agricultural sector accounts for nearly half of our greenhouse gas emissions, and has been associated with declining water quality and biodiversity loss."

It is not a solely domestic problem. Our food system is just one swinging chair on a creaking global ferris wheel.

New Zealand produces enough food to feed 40 million people. But 90% of it is exported, making us "the most extreme export-oriented nation in the world", Prof Campbell says.

Those exports include $16 billion worth of dairy, $3.9 billion of sheep meat and $3.7 billion of beef each year.

As a result, we might not be producing enough vegetables to provide five servings a day for our population of five million, Auckland University of Technology emeritus professor of nutrition Elaine Rush says.

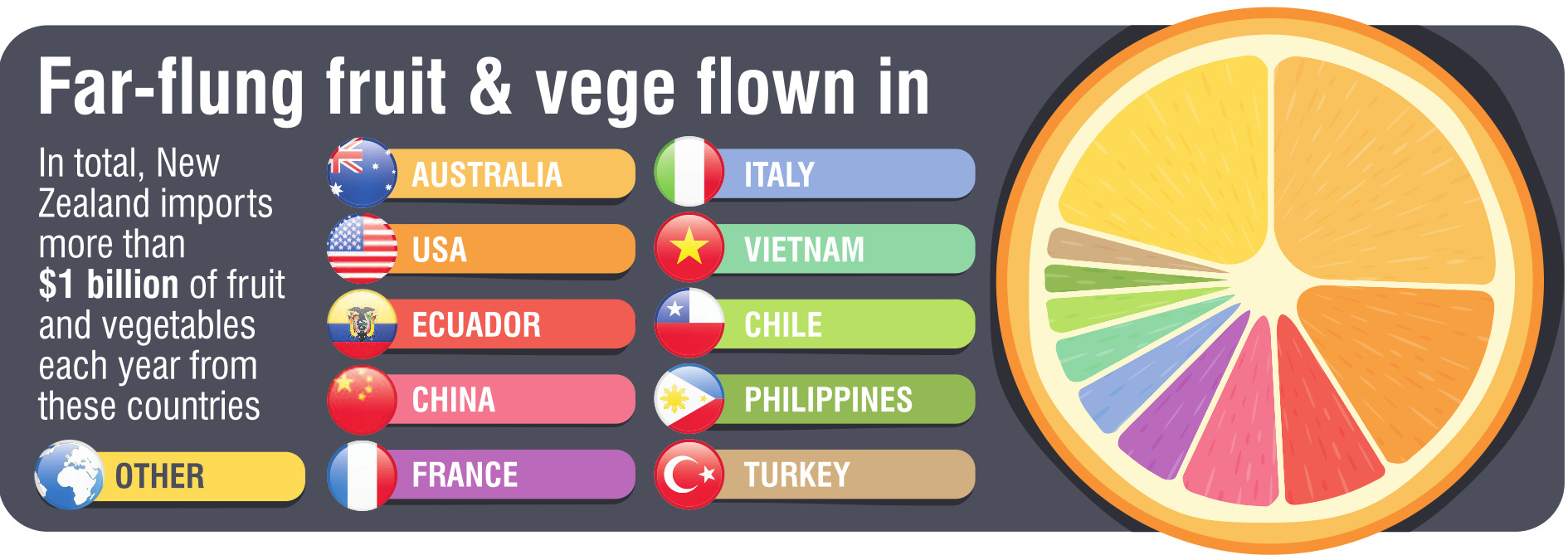

And while we export mostly high-nutrient foods, in addition to importing fruit and vegetables we bring in a lot of nutritionally dubious foods high in carbohydrates and sugars.

"We’re fat, famished or starved in a land of plenty," Prof Rush says.

"A country that can produce more than enough high-quality food should feed its own first."

Internationally, the whole edifice appears at breaking point. Although enough food is produced worldwide to feed everyone, 811 million people do not have enough food. An estimated 44 million of the great unfed are at risk of sliding into famine, the most extreme form of hunger, the United Nations (UN) reports.

This is being exacerbated by the Covid-19 global pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Normally, Russia and Ukraine produce 30% of global wheat exports and are the source of half of the wheat distributed by the UN World Food Programme.

Deputy Prime Minister Grant Robertson has stated it plainly.

"This genuinely is a global problem," Robertson told Radio New Zealand when asked about Kiwis’ dramatically increasing grocery bills.

"We've got supply chain constraints. China's got lockdown, so they're closing their ports."

Prof Campbell can add to that explanation.

He says the global food system fiasco has indeed put New Zealand in a particular pickle, but one with special features of its own making.

New Zealand, he says, has been "one of the most vigorous supporters" of free trade in agricultural products worldwide.

Until four decades ago, it was accepted worldwide that agriculture should be under each country’s control, not included in free trade deals lest it undermine food security.

But in 1985, a year after New Zealand began its decades-long neoliberal free market experiment, agriculture was included for the first time.

It was a decade before that seminal change came to fruition, birthed as the World Trade Organisation’s first global free trade agreement. With it came huge changes. Since then, Prof Campbell says, the only other free trade deal to really deliver for New Zealand, for better or worse, has been the one with China, signed in 2006 and activated two years later.

"It just went crazy," Prof Campbell recalls.

"From the moment it was signed — and it became clear that the China market was opening up for us, and that we would have this very brief moment of being the only Western country exporting tariff-free into China — the money began rushing into dairying."

One significant effect of that focus on a narrow band of high volume export products has been a reliance on importing other foods.

"So much of that food that's getting imported, is channelled in through the big corporate retailers," Prof Campbell says.

"If we had more food staying onshore, the opportunity for more local or medium-sized food producers and manufacturers in New Zealand would increase."

In essence, Prof Campbell is saying that New Zealand’s tunnel-visioned commitment to primary produce-based, free trade-enabled, export-driven growth has given Kiwis a broken food system in which big players make exorbitant profits, consumers struggle to afford food too often imported from overseas and foodbanks cannot meet demand from an increasing number of people in severe hardship — all in a country that grows enough food to feed eight times its population.

In that sense, supermarkets are just the visible cash cows atop the crumbling national and global food system iceberg; those queueing up at food banks, the choking coal mine canaries.

But right now, New Zealand has no back-up plan, Prof Campbell says.

"We haven't had the long-term policy discussions about what appropriate agricultural land use looks like in New Zealand.

"So we're stuck in need of a Plan B."

Unsurprisingly, Prof Campbell, who has been looking at these issues for years, has a suggestion.

When it comes to food, New Zealand needs to export less and import less, he says.

This would have ecological, political and economic benefits.

"Ecologically, it's better to be consuming closer to where you're producing."

This enables consumers to better know the work conditions their food is produced under, any animal welfare issues and environmental impacts.

"You can't say that about all the food we import. You can claim that is the case, but you can't really know."

Growing more food here would also help focus political attention on food system issues, he says.

"The more that's happening onshore, the more politically empowered that group gets and the less likely they are to be exploited by large corporate actors."

And while some economists might disagree with him, Prof Campbell believes more food grown and consumed here would give an economic boost to more New Zealanders.

"My opinion is that a greater distribution of income-generating potential across small and medium-sized food production, manufacturing and retailing in New Zealand is more resilient and distributes the value of that food dollar better around a great number of people, rather than simply having it tied up with corporate food exporters."

Dr Niki Bould and her fellow partners at Ahika Consulting have proven it can be done, in theory.

The Otago-based, community well-being specialists led a 2016 project to see whether the region could sustainably supply its own food needs. The aim of the Ministry of Primary Industries-funded research was to promote more resilient, locally-focused food systems in New Zealand.

The Otago Food Economy study found the region would only need to use one-fifth of its land area to produce all the food it needs to be self-sufficient, Dr Bould says.

The report noted Otago produces significant volumes of dairy products and red meat, "reflecting the export-focused nature of New Zealand primary production".

In the case of Dunedin, the city could reduce its dairy production by 85% and still meet local demand, freeing up land for other agricultural activity.

"There are strong opportunities to diversify production away from the core export commodity products ... to vegetables and fruit, enabling stronger self-sufficiency," the report states.

"The opportunity cost associated with changing land use to less profitable food production is the biggest and most obvious impediment to such a transition."

That was six years ago. Ongoing and escalating turmoil in the global food system could tip the balance in favour of shorter, local supply chains.

Otago Farmers’ Market, and others like it, have been a successful expression of that vision.

The momentum is growing.

Our Food Network Dunedin, for example, runs projects such as the Neighbourhood Food Harvest to promote local production, distribution and consumption of food.

The Dunedin City Council has been running workshops to examine the local food ecosystem, identify what is broken and find ways to fix it.

The council has also part-funded Our Food Network’s part-time school garden facilitator Kathryn Davie who helps the pupils of three low decile schools grow and cook their own fruit and vegetables.

Davie readily admits the school garden project is one of many similar endeavours throughout the region and around the world. It shows the need to re-connect with locally produced food is widely felt, she says.

"If we want to reclaim our food system, we need to make sure the knowledge is planted in the next generation," Davie says.

"The kids are always excited ... They really have that joy of sharing food."

Not taking significant steps is not an option, Prof Campbell says.

"If we don’t, it’s only going to get worse. Because the global food system is vulnerable to the escalating cost of fossil fuels.

"We need to decarbonise, encourage small local food enterprises to get bigger and develop a New Zealand food culture".

Tayla Mokotupu does not know she is the future.

Talking with her Mum about the vegetables they will take home for tea, she does not think about being part of an attempt to explore a better, urgently needed alternative to our broken food system.

She simply knows that she now enjoys planting seeds and watching them sprout, that she loves the idea of growing food and bringing it home to eat, and that she quite likes the taste of custard with sweet, tangy, freshly-stewed rhubarb.

Comments

Fairyland.

In the 1950s people grew much of their veggies in their back yards. Almost every weekend my father was planting and tending to veggies, as were the neighbours on both sides and over the back. During the week mum, and the other mums were weeding, perhaps a day a week, as did I and my school friends by the time we were 10.

The greengrocers were for bananas, oranges, and a winter sack of potatoes and a box of winter keeper apples.

Mums spent weeks preserving seasonal fruits ... with jars filling cupboards, and exchanges of delicacies, sauces, and conserves.

We ate a lot of mutton, corned beef, and oxtail casseroles ...

At my supermarket I see seasonal fresh fruit and veggie slop backwards and forwards over the Tasman, and the freezer chests are filled with produce world wide.

The world has moved on. The 1/4 acre section with the back half committed to vegetables has gone. Fathers do other things at weekends. Mums have careers. We expect oranges, bananas, avocados, raisins, dates, and more exotic stuffs to be part of our regular diet ...

Excellent content but terrible headline. People here need to know more about the Dunedin City Council's efforts regarding this serious problem, which is just going to get worse.