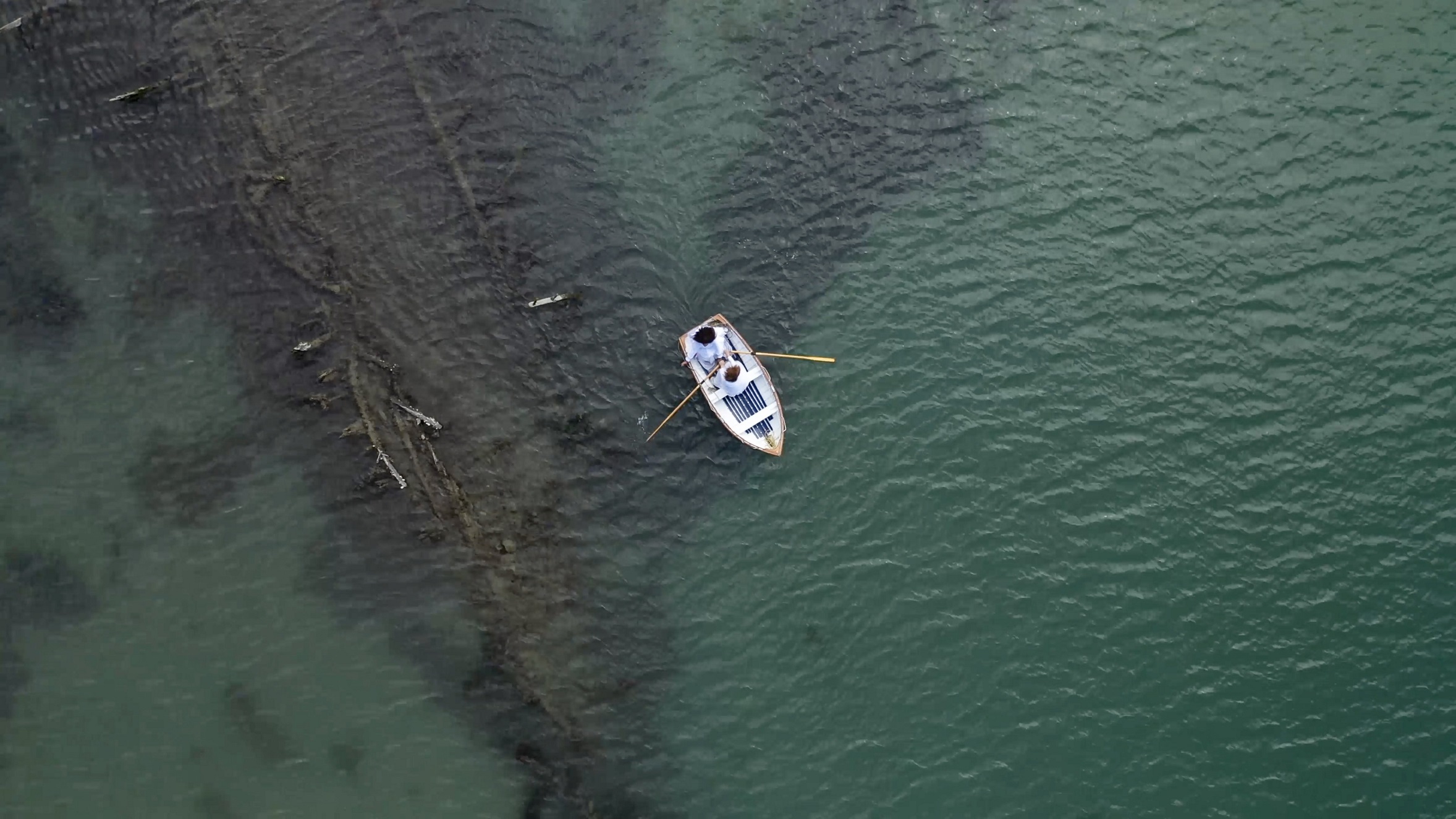

Being able to see and row out to the wrecked remains of the Don Juan is still incredibly surreal for Jasmine Togo-Brisby.

In 1863 the schooner took the first Pacific Islanders from their home islands to live and work in Queensland, Australia. Many were forced or coerced to work as labourers on Australian plantations in a practice sometimes known as "blackbirding".

They included Togo-Brisby’s great-great grandparents, who were taken from Vanuatu as children.

"That was the one that triggered the influx of this as a trade; the Pacific became a highway for slave traders."

For Togo-Brisby to discover the Don Juan in Deborah Bay, where it was grounded due to its unseaworthy condition nearly 30 years after it arrived in Otago as the Rosalia in 1874, conjured up all sorts of feelings.

"I had never conjured up the thought it possible. To find that it is still around and you can go and look at it is just surreal. I just assumed it had disappeared, but to find it still exists here in Aotearoa just a short flight away from me is quite remarkable."

Togo-Brisby discovered its existence on a short trip to Dunedin in 2017, but it was not until she received the Tautai artist residency at Dunedin School of Art in 2019 that she began to research and investigate it. Being in the city meant she had easy access to archives such as the Hocken Collections to do that research.

Seeing it for the first time was "confronting and still is confronting".

"No amount of preparation that you could give yourself could prepare yourself, and I did try to prepare myself."

She consulted her mother Christina Togo, her elder, who is often part of her art practice, about what the vessel meant to their community and what needed to happen to the remains of the ship outside of art.

A blessing was proposed to acknowledge what happened in the vessel, which was also used by slave traders before being pressed into service in the Pacific.

"From our culture we are clearly the only ones maybe who have been to the site and see it as such a traumatic site of memories."

Togo-Brisby then began to think about how as an artist she could capture that moment of their journey, as well as reconciling how to put what happened with the vessel to rest.

"It has been a very complicated work for me."

For Togo-Brisby the salt water surrounding the ship acts like an archive, preserving it, and she views it as an archival site even though it is not treated as one.

"I find that really interesting."

It was not until 2020, just before the pandemic hit, that Togo-Brisby’s ideas coalesced into a project and filming began.

"It took months and months of planning — obviously when you are trying to work with the remains of a ship which is only revealed when the tide goes down — and then the videographer, the drone, all of those things."

An important aspect of the film was to get a drone up so people could see what the "shadowy skeleton" looks like as a whole.

"It only takes like five minutes for the tide to turn so we had to be quick; it was crazy but the powers that be must have been on my side, the sun was perfect, the tide perfect, but it still wasn’t an easy job to capture that."

From talking to people from the Port Chalmers community, she is aware the ship has different associations.

"For some the ship has been a water playground. It’s just so complex as it has also brought joy to people."

Togo-Brisby very much wanted to get up close to the wreck.

"It seemed a very important part of the process. There is something very real about being able to touch it."

So they filmed as Togo-Brisby and her mother rowed out to the wreck and around it, launched off the shore by her daughter Eden Cassady. They spent two hours out on the water.

"I rowed the boat and Mum sung in tongues and prayed for the people who had been on that journey on that vessel."

"I used her singing ... I found it was quite ambiguous to have her singing in tongues."

Editing the film has also been difficult as she grapples with the many conflicting feelings around the ship.

"For myself it has helped me process, speed up the healing and reconcile its existence."

The final work Mother Tongue is nine and a-half minutes long, and she feels it is a "genuine document" of the process.

"Going into it I did not know if I would have something to work with in the end, whether I’d have an art work or it might have just been something I had to do for the space."

However, each time she returns to the site, she gets taken back to that first moment when she saw it.

"It was confronting, emotional and very surreal, how is it possible to be looking at this? This is the ship, my ancestors lay in the hull of that ship. There should be so much distance between me and that in time, it’s hard to come to terms with on an individual level and always will be. It feels like its a part of me that has been down there all this time."

Friends have offered to throw stones at it on visits or asked if she would like to burn it down, but Togo-Brisby is horrified at that idea.

"It’s s.... It is part of us, we have to respect it — not that I respect slavery in any way, but respect what our ancestors went through. Personally to me to do that would be dishonouring them. Like I say, real complicated.

"For it still to be there shows how recent this history is to us in this region."

The whole situation feels very serendipitous to Togo-Brisby — she was completely unaware of the ship’s presence in New Zealand when she moved here six years ago to further her study into Pacific theory and dialogue.

"If I hadn’t moved to New Zealand I probably wouldn’t have known about it."

As a fourth-generation Australian South Sea Islander, with ancestral lineage to the islands of Ambae and Santo of Vanuatu, Togo-Brisby’s art practice has always looked into the history and impacts of the South Pacific slave-trade.

"It’s a cliche, it was about being the change in the world for her, not wanting her to have the same experience as me, which is [that] our culture is quite invisible even in Australia, outside of the sugar towns. "

So she headed to art school in Wellington, aged 26, where she studied fine arts with honours at Massey University.

"I fell in love with this place and didn’t want to leave."

Togo-Brisby has always loved making things, which often translated to sculpture or photography — some of which was exhibited in "Birds of Passion" at the Dunedin School of Art during her residency .

"I like mastering things then making them do what I want."

Video, such as her latest work, is not something she uses often.

"I only use it when the research is calling for that medium. I think I’ve only done two video works and only when that medium was needed to convey what I need to talk about."

As well as the film being exhibited at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Togo-Brisby’s first big commission has gone on show in Auckland Art Gallery’s Declaration: A Pacific Feminist Agenda.

"It’s really exciting. Given the invisibility of the old stories to be included in this exhibition is so special and so important."

The work is designed to be suspended from the ceiling and features her own ceiling tiles in the shape of a ship about 10m long.

"It’s rather big. It hovers over you about 2.5m off the ground so when you walk into the room [it’s] empty except for the art work."

She finds it interesting that within two weeks she is exhibiting at both ends of New Zealand — in one she encourages viewers to look down at a ship, while in the other she encourages viewers to do the opposite by gazing upwards.

To see:

Mother Tongue, Jasmine Togo-Brisby, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, April 9- June 12