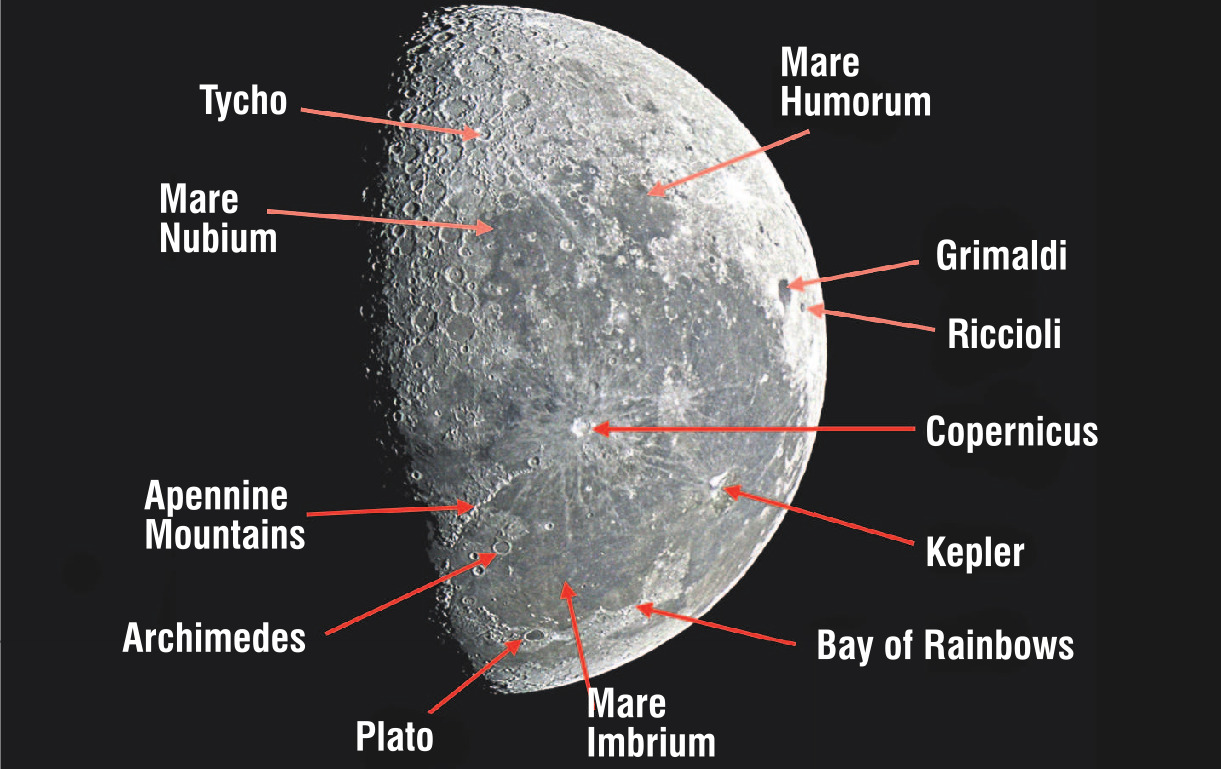

Some lunar features such as the dark lunar mares are easy to see using just your eyes. However, if you want to study the moon in detail you need a pair of binoculars or, better still, a telescope. Even a small telescope reveals myriad craters, mountains and valleys. Undoubtedly, it is possible to spend many happy hours exploring the fascinating but desolate surface of the moon.

The system of names used for features on the moon was introduced in 1651 by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Riccioli. There had been previous naming schemes proposed, some dating back to the invention of the telescope, but none were widely accepted.

A Jesuit priest by training, Riccioli decided to name the more prominent lunar regions of the moon after terrestrial weather or frames of mind (for example, Mare Nubium is the sea of clouds while Mare Humorum is the sea of moisture). He then divided the rest of the moon into eight sectors, populating each with craters named for great astronomers grouped by philosophy. That’s why the Greek scientists Archimedes and Plato can be found together in the Sea of Showers and why Copernicus, Tycho Brahe and Kepler, the blazing stars of 15th- and 16th-century astronomy, have bright rayed craters named in their honour.

In preparing his lunar atlas, Riccioli felt it appropriate to recognise his own contribution by naming prominent craters close to the edge of the moon after both himself and his collaborator Francesco Grimaldi. While it is unclear whether Riccioli himself was a supporter of the (at the time hotly debated) sun-centred model proposed by Copernicus, he did name a prominent crater after the astronomer. It is in Oceanus Procellarum (the Ocean of storms), a location that, perhaps, reflects the stormy reaction garnered in the faithful to Copernicus’ revolutionary model of the solar system.

- Ian Griffin