Two books detailing the early history of New Zealand piqued Peter Simpson’s interest and got him thinking.

He was introduced to one on the other side of the world, while studying in Portugal in 2017 — A Voyage Round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5, Georg Forster, 1777.

‘‘It’s been about a four-year interest I’ve had in the book.’’

Published six weeks before Cook’s official account, the text’s contribution was to be more than a collection of facts, which differed from the majority of travellers’ accounts at the time. Forster used the text's narrative to frame and give context to the voyage’s many scientific ‘‘discoveries’’.

Around the same time Simpson was reading Anne Salmond’s The Trial of a Cannibal Dog and two things stood out — a painting by Tupaia, a ‘‘beautiful’’ watercolour and a small excerpt from the book about a Maori person stealing a copy of the first novel in English, The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling by Henry Fielding.

‘‘I wondered what that Maori person thought of the book that they couldn’t read. That was something that really grabbed me. There’s a similar thing in the Tupaia painting.’’

It gave him the idea of treating the book how a Maori person in those circumstances could have done it when they stole it.

That has led to a three-part exhibition, ‘‘Literature’s arrival to the Pacific’’.

‘‘The book is like the thread that goes through all the work.’’

It starts with a pallet of Endeavour-branded water bottles — a reference to the discovery of New Zealand — which have a page from the first edition of A Voyage inside them.

‘‘So I made a sculpture out of the soda water bottles.’’

Simpson (Ngati Maniapoto, Waikato-Tainui, Ngati Paoa, Ngati Tamatera) also created a painting, Gordon, which references New Zealand artist Gordon Walters. It is a ‘‘zoomed-in’’ koru painting with a page of the first edition glued to the canvas and then painted with Indian ink.

‘‘The page itself becomes negative space within the painting.’’

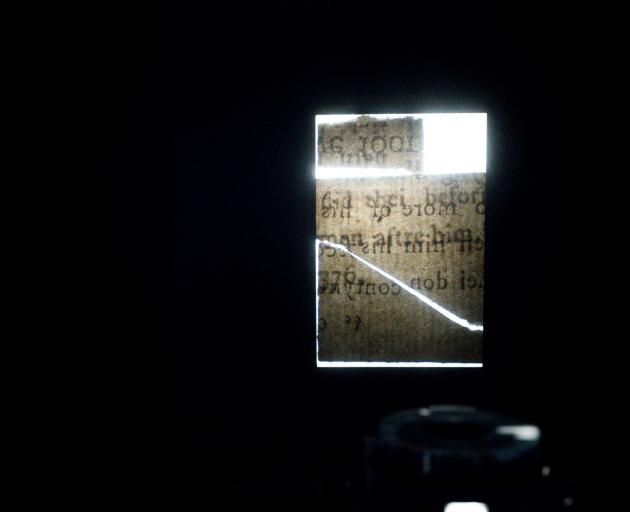

Further into the gallery, a film of the book shows, utilising an old slide projector with 80 slides moving on a loop.

‘‘They’re quite lovely. I’ve cut up little bits of the book and put them into the slide and then made images with the bits of the book. You can’t read the text but it makes an abstract film.’’

It has been a bit of a process to get the project to fruition, as Simpson lives in Auckland and has been in lockdown for much of the project’s duration.

A decision was made to go ahead with the exhibition despite Simpson still being in lockdown. The works had initially been scheduled to be shipped the day after lockdown was announced.

‘‘It was going to open in September but now we’re here in November, so it’s been slightly frustrating.’’

‘‘You want to find a resolution to it at some point. It’s still exciting. Maybe I can come at the end of the month — who knows.’’

Through instant messaging and photographs, Simpson has been directing the curators as to where to place the pieces.

‘‘It’s the best we can do.’’

Simpson, whose grandfather was Dunedin general practitioner Olaf Simpson, but was himself born in Wellington, is no stranger to lockdowns and the problems they cause, having come in March this year from the United Kingdom where he had lived for 11 years.

He had planned to come back home earlier to begin study on a PhD, but Covid-19 intervened.

‘‘I’d been away for a long time and I wanted to come home. I’ve done a lot of lockdowns.’’

Simpson was in London at the beginning of the pandemic, which he describes as ‘‘quite difficult’’.

He then moved to Norwich to escape some of the difficulties of city-living in a pandemic and began the process of trying to get a spot in MIQ to come home.

Having grown up in Auckland, Simpson has settled in the city again, but is now looking to do his PhD at Massey University.

‘‘It took a lot longer to come back. So this lockdown seems very familiar to me.’’

It was in the UK where Simpson did his fine arts degree at Chelsea College of Art, University of the Arts London in 2013 and then his master’s at the Slade School of Art, University College London in 2019.

A love of research has driven his academic pursuits, but he cannot give up making work.

He wants to improve his writing skills through the PhD but also look at how the two parts interact together.

‘‘It’s a pathway to having a practice to teaching and writing, having it all be symbiotic together.’’

His practice has always been research-based.

‘‘I really enjoy researching and reading and going through historical material and I also really enjoy the material aspect of how objects can represent ideas in history and then you can like write with the materials or images.’’

This latest project is a good example of that, he says.

His interest in the arts began at school as he is dyslexic and had difficulties reading.

‘‘There is something quite freeing about moving things around which I found quite helpful as a child. It is also one of those things you get attached to and you don’t quite know why as a child.’’