Some days, Graeme gets a living wage. Other days, he earns $2 more.

In the world of supermarket workers, he is one of the lucky ones.

Graeme is not his real name. None of the supermarket workers, nor their mums, mentioned in this article were willing to take that risk. That tells a story in itself.

Graeme is in his twenties and has been a supermarket worker for more than five years. He must be doing a good job, because he has been given extra responsibilities. That means, a couple of days a week his pay climbs from a few cents above the living wage, $22.75 an hour, to a few cents above $23 an hour.

And, yes, he agrees, among New Zealand’s 57,000 supermarket workers he is one of the fortunate ones.

"I think it’s because we have a bloody good union behind us," Graeme says.

Most non-unionised supermarkets pay ordinary employees the minimum wage, $20 an hour.

Graeme works at a Countdown store, in Otago.

He might be counting his blessings, but it is still a battle to build a life on that income.

To his credit, this year, he and his partner put a 10% deposit on a house.

The deposit was only achieved by saving hard and not leaving home until he bought his own place.

The mortgage payments are met by having a boarder living with them in their two bedroom house.

Graeme is aware of the huge profits being made by New Zealand’s supermarket duopoly, Woolworths NZ and Foodstuffs. Last year, Woolworths NZ supermarkets had a $202million net profit, while Foodstuffs’ North and South Island co-operatives, which run Pak’nSave, New World and Four Square stores, had a combined $407.3million operating profit.

"I’d appreciate them using some of those profits to make everything more comfortable for us workers," Graeme says.

It is not only the tens of thousands of supermarket workers who are noticing the growing gap between wages and profits. For the past three decades, wages throughout the New Zealand economy have lagged behind the value of what workers are producing. A cost-cutting "race to the bottom" has resulted in a low wage economy that is most keenly evident in sectors such as supermarkets, bus driving and forestry but is also widely felt in many other workplaces. Since 1991, across all Kiwi employees, the gap between real wage growth and labour productivity growth has widened to an average of $6.10 an hour.

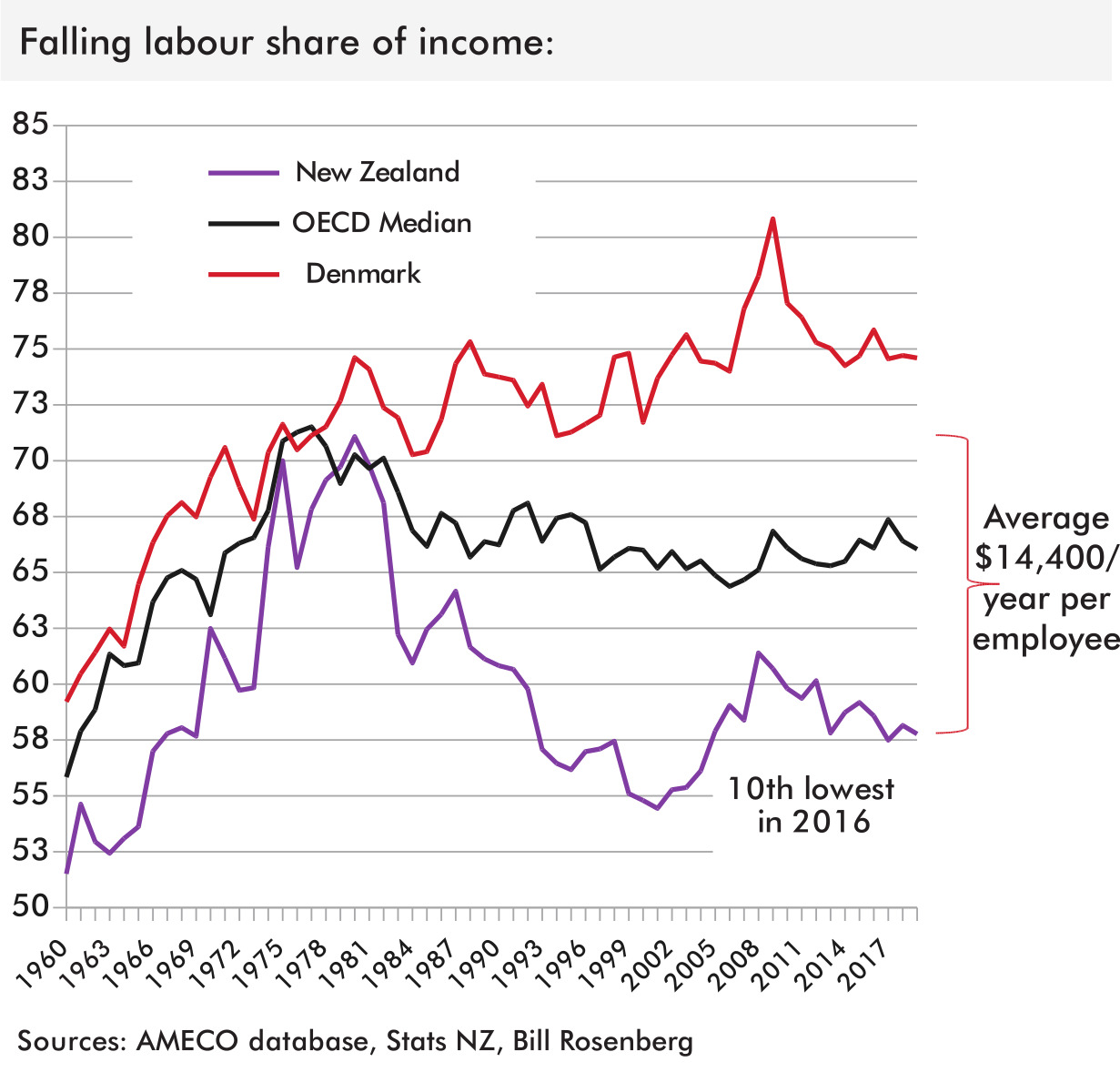

Another way of getting at the same picture is by looking at the labour share of income — the share of the national income that goes to employees compared with the share that goes to owners of capital, business owners. Since the mid-1970s, the labour share of income has risen in Denmark and declined somewhat in most OECD countries. It has dropped about 15% in New Zealand, by an average of more than $14,400 a year per employee.

Productivity Commission economist Bill Rosenberg has shown that in New Zealand the labour share of income fell most precipitously after the 1991 Employment Contracts Act reshaped employment relations in New Zealand, dismantling the influence of trade unions and tipping the balance of power firmly towards employers.

Last year, the WEF, which holds an annual (covid-permitting) gathering of the world’s richest and most powerful, in Davos, Switzerland, issued a warning that declining labour income share "has significantly driven economic inequality ... reflected in huge wage disparities".

The WEF report urges government and business to rebalance the playing field in order to reverse "[a] weakening social fabric, eroding trust in institutions, disenchantment with political processes, and an erosion of the social contract".

In other words, sort things out or face possible revolution and anarchy.

New Zealand now has levels of inequality on a par with the United States. Statistics released this week show the wealth gap has worsened in the US where, for the first time, the richest 1% of the population owns 27% of the country’s assets.

In New Zealand, the top 1% own 25%.

This inequality is seen starkly in housing affordability.

The median Dunedin house sale price is now $642,500; more than 16 times the median national income.

This week, a Royal Society report revealed a third of New Zealand households spend 30% or more of their income on housing costs. The differences in housing are a large contributor to inequity in New Zealand, the report says.

Rachel, not her real name, is acutely aware of the challenge that poses her children and, even more so, people worse off than her family.

Two of her children have worked at Otago supermarkets after school and while studying at university.

"The only pay rises they have received are when the minimum wage goes up," Rachel says. "However, the supermarket owners are taking in oodles of money.

"It’s not so bad, as this won’t be their career. But for some people it will be and it definitely will not be enough to service a mortgage."

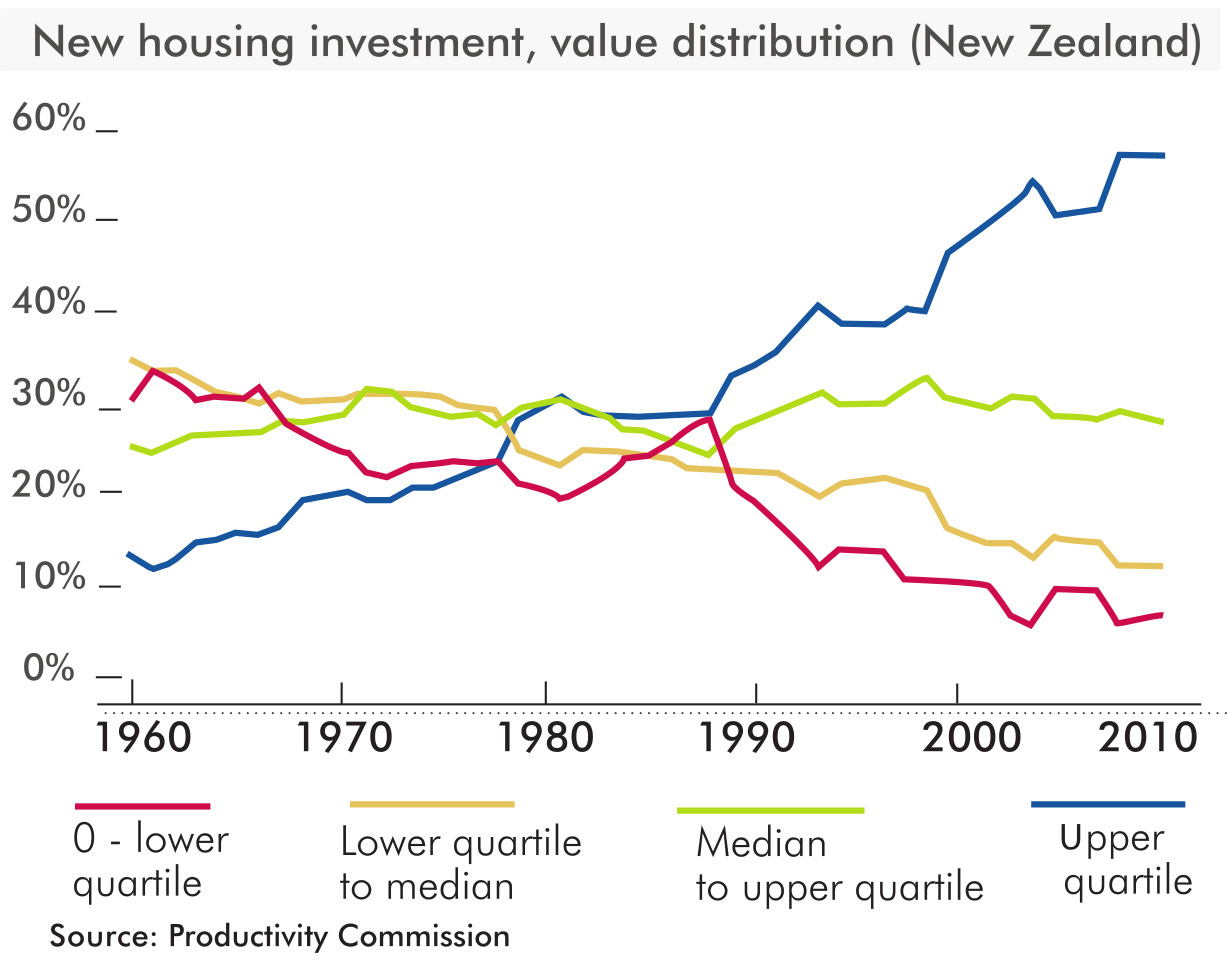

Once again, the problem can be traced back three decades.

Rashbrooke, who is a senior associate at Victoria University’s Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, points to a 2012 Productivity Commission report that tracked new housing builds since the 1960s. It graphed new houses by their value. From the Employment Contracts Act onwards, the number of lower value new builds tanked while the number of more expensive new houses took off.

"All these things fit together," Rashbrooke says.

"The Rogernomics idea that you get government out of the way and just let people do their thing ... leads to a housing market that isn’t being shaped and directed properly by government.

"So, the widening inequality ... goes together with the widening inequality in housing. The result is an economy structured around the needs of wealthy people to a much greater extent than before."

Underlining that, a week ago the Otago Daily Times reported a surge in top-end Southern houses being bought online, sight unseen, including three properties in the Queenstown area going for between $14.5million and $16.1million.

Some small pushbacks have happened.

Pay equity is one. Amendments to pay equity legislation have resulted in pay rises for care and support workers and teachers’ aides. Other claims are in process.

The living wage is another. Organisations and businesses, representing more than 250,000 workers, have signed up to ensure their employees get a basic liveable income. In Otago, they include Ocho Chocolate, Queenstown Airport and the Dunedin City Council. Many others, including Waitaki District Council, are being urged to get on board.

Progress is slow.

But one significant change on the horizon is Fair Pay Agreements.

Fair Pay Agreements will create industry-wide standard pay and conditions for groups of employees. If 10% of an industry’s workforce, or 1000 workers, call for a Fair Pay Agreement then employers and unions will have to bargain for minimum terms and conditions that will apply throughout that industry.

"They’re a key part of our plan to leave behind New Zealand’s low wage culture," Wood says.

Legislation to set up the Fair Pay Agreements system will be introduced to Parliament by early next year and passed in 2022.

First Union’s national retail organiser Ben Peterson hopes supermarket workers and bus drivers will be first cabs off the Fair Pay rank.

"But there are many other areas where aggressive competition has corroded safe and secure work," Peterson says.

Similar systems establishing minimum employment standards across a sector or occupation already exist in countries including Australia, Europe and Singapore.

But after 30 years of some of the most flagrant neo-liberalism of any country, it is seen in New Zealand as a big step to the left.

Supermarkets, under the gun for their monopolistic ways, are circumspect in their reaction.

Ditto for Foodstuffs.

"We look forward to understanding more about the process and methodology ... and we await the details on Fair Pay Agreements patiently," Antoinette Laird, Foodstuffs’ head of corporate affairs, says.

Business New Zealand is more forthright.

Kirk Hope is chief executive of the business lobby group that has more than 100 members, representing 67% of New Zealand’s GDP. Its members include Foodstuffs South Island and Woolworths NZ.

"These large collective agreements would result in a loss of autonomy for the businesses and people involved."

Interestingly, even staunch supporters of the Fair Pay Agreements proposal have some reservations. Although, those concerns are primarily that it does not go far enough.

"I don’t think anyone really thinks Fair Pay Agreements will restore labour income share," Rashbrooke says.

"There have been little bits of good things happening. But I think we need a really good push."

Rashbrooke has come to that conviction through his inequality research. He says it is clear that inequality is now so entrenched that New Zealand has a class system.

It is a central concept in his new book, Too Much Money, due out next month.

He shows, not only has there been a huge concentration of wealth by a small group, but wealth is giving those people many other advantages.

"You can no longer say there is equal opportunity in New Zealand, when wealthy children are getting so much of a different start in life to poorer children.

"There are these groups that don’t just have wealth, they have all these advantages that put them in a different position in a hierarchy. And there’s some sort of stability to that hierarchy, because it is getting passed down to their children. That is the definition of a class system."

The "really good push" required to restore the prospects of workers might be the "default unionism" proposal Prof Mark Harcourt has been researching.

Professor of human resource management, at Waikato University, Harcourt says the demise of trade unions has been shown to be one of the biggest factors in growing inequality.

"The collapse of unions was overwhelmingly because of the institutional changes brought on by the Employment Contracts Act. It was never about employees’ preferences," Harcourt says.

Once their role was undermined, unions’ influence and membership spiralled downwards together. The Employment Relations Act arrested that fall, but nothing more.

"Free riding" then became an increasing problem. Because employers cannot offer worse pay than what is in the workplace collective contract, people are tempted to take the benefits without the costs of union membership.

Kelly, not her real name, worked fulltime at a Foodstuffs supermarket in Otago, until this year.

While employed there, she got two pay increases on top of minimum wage rises; one 5c and the other 15c.

At the time, she thought union membership was "a waste of time". But with hindsight, she has "a bit of regret about that now".

Not seeing a decent future on supermarket wages, Kelly left and is now accruing debt while she studies.

The default union concept could have made all the difference.

It would make union membership the default position for new employees. This would be the trade union version of KiwiSaver — everyone is in, unless they opt out.

It is surprisingly popular.

During the past two years, Harcourt and fellow researchers have conducted three surveys on default unionism.

Consistently, about 58% of the population supports such a move.

Curiously, an even higher ratio, 2:3, say if default union membership was introduced they would stay in rather than opt out. That climbs to 85% if employers or government were to cover membership fees.

Default union membership finds least favour with those earning more than $200,000 a year (still 40% support) and is about 7% more popular with women than men.

"I don’t have any doubt that labour share of income would increase," Prof Harcourt says.

"Whether people like or hate the union default, almost all agree that unions would be more powerful and things will change."

It is not just for the sake of those on low incomes, the Graemes and Kellys, that significant change is needed, Rashbrooke concludes.

If people are not given enough to take care of themselves and prepare for the future, it is a debt everyone will have to pay.

"If we just allow precarious work to continue, there will be a huge cost to all of us as taxpayers in 30 or 40 years’ time, providing more for these people who should have been getting better conditions now."

Comments

Labour Day! Exactly the right day to discuss employment issues. Free enterprise wins and gives jobs to those who do the work and get on board with the means of supply and demand. Free the market and it will deliver IF we are in a climate where moral values are not dominated by human desire to get something for little effort or by those who want to screw their staff at every turn. Strong unions with a moral base will help but the boss has to be a person who genuinely cares about the staff because they are human beings and not "human resources" or "economic units."