"One of the things that I've discovered in my research ... is the ability to time travel."

It is the sort of statement that usually has one calling emergency psychiatric services, but the person making this wild claim is Prof Susan Krumdieck, a noted academic at the University of Canterbury, co-leader of the Global Association for Transition Engineering and director of the Advanced Energy and Material Systems Laboratory.

Prof Krumdieck is an engineer whose research is focused on the implications of the Earth's rapidly declining fossil fuel resources. She says we can no longer afford the world that has been possible for the past two centuries. To explain, she makes the time travel claim.

"Going forward 100 years is really informative," Prof Krumdieck says.

"And 100 years in the future, when I go there, I find that fossil fuel is no less useful than it is now. That the things you can do with fossil fuel are still 100 times better than what you could do with any other fuel."

The energy research methodology Prof Krumdieck has developed allows her to see what is going on with our energy use now and in the future.

It is not looking good, she says.

For the past 220 years in the case of coal, and 150 years in the case of oil, we have been mining and drilling fossil fuels as fast as we can. That has enabled us to build the industries, cities and transport systems of today.

But those fuel sources are getting harder to find and costing more to extract.

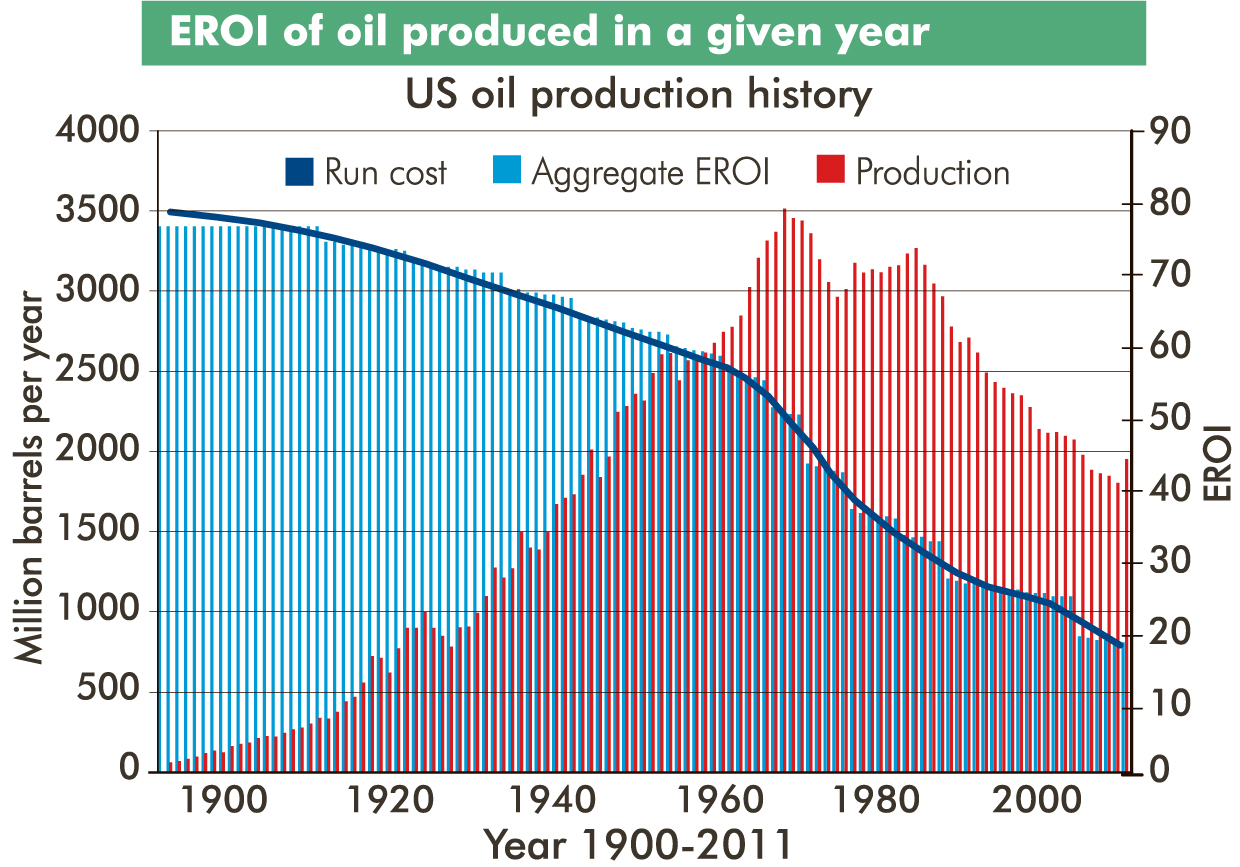

Oil, for example, had a return on investment of 80:1 at the start of last century. It was cheap to get at and use, so it allowed plenty of growth and development, but as we have used it up, finding and extracting oil has become increasingly difficult and expensive. More energy has to be used in the process of getting at the oil in the ground, which means there is less of it left over to maintain what we have already built, let alone create new things.

"We can spend really good oil on getting this stuff. You can't run an economy on that."

The only incentive, and the reason it is being done, is that scarcity drives up the price, making the higher investment worthwhile.

But all it is doing, in the long run, is using an energy resource we can never replace but desperately need.

The same goes for coal.

High-quality coal is needed for a range of essential products such as the steel that is used to construct buildings taller than only several storeys high.

Without coal we do not have steel, cement or glass, except in tiny quantities compared with today's production levels.

Prof Krumdieck's research also enables her to "see" our energy future.

"So those people there, 100 years from now, fossil fuel to them is so much more valuable than it is today, they don't waste it at all.

"And they work really hard to not use it, because it is so valuable. And that's in their design, it's in the ways their cities are laid out, it's in the products they use.

"And so what I know for sure is that between now and then we transition to that."

We will make that transition, she says, either by choosing a better-late-than-never, rapid shift in how we live, or by using our fossil fuel resources until they are almost depleted and society as we know it collapses.

"The skyscrapers built today are going to be less and less maintained, over time. And parts of them are going to be abandoned after a while and maybe used for long-term storage or something as opposed to fancy offices.

"The materials that we have already invested in, the way we've invested, we cannot afford to do that again. It's just not there."

What would happen if we don't transition is like asking what would happen if we don't win the war, she says.

"If we lose, we lose and we have to deal with the consequences. Losing in this case means both failing to downshift through design and ... overloading and hitting the failure limits of greenhouse gases and species extinctions."

Unsurprisingly, rather than waiting for collapse, Prof Krumdieck advocates a swift and dramatic change in order to stop polluting the atmosphere and to spin out our fossil fuel reserves for as long as possible.

"I would say we should drastically reduce our fossil fuel consumption because we are going to need it forever."

Her vision for this global redesign is as comprehensive as it is radical.

We need to re-organise and rebuild existing cities and rebuild and electrify national rail systems.

"What is this [existing] system doing for us and costing us? And if there are better ways, how do I provide that better way?

"One thing I've seen in my research is that anywhere on this planet you give people a walk-able neighbourhood with rapid transit connections to the business districts, or wherever they have to go for their work, it will sell out off the plan."

She also predicts a significant proportion of urban dwellers will move to rural areas and be retrained for primary production.

"One hundred years from now, the fuel we used to do the work for us is no longer there.

"One farmer with some pretty impressive machinery can do the work of 100 people. Take away the oil, and you get those 100 people back on the land."

Prof Krumdieck has firm views on who must lead and bring about this radical redesign of life built around reducing the use of, and conserving, fossil fuels. They are, in her opinion, the world's engineers.

Engineers have designed the world we have. They must do it again, she says.

"Yes, en masse. And I have heart in that, because they have done it before."

A century ago, 62 engineers came together to develop the discipline of safety engineering. It has given us the safety-conscious world we have today.

Now, to bring engineers together to design and engineer a global energy transition, Prof Krumdieck has helped establish the Global Association for Transition Engineering, of which she is a co-leader.

Worldwide, 2600 engineers have signed up, so far.

Her message to engineers is simple.

"Look at where we are going to end up and be a pioneer in that. That is the transition that needs to be engineered."

Saying engineers have to take the lead does not let the Government and the public off the hook.

Those in political power need to fund and regulate for the transition. They also need to fund research and education in support of it, she says.

The public's role is to hold engineers to account.

"They must figure out that engineering exists and they must turn around and look squarely at any engineer they know and say to them, `You know this transition engineering thing, you're doing that, right?'."

Whether we transition in time or after a collapse, New Zealand is somewhat at the mercy of global forces. But not entirely, Prof Krumdieck says.

"Can we affect what the rest of the world decides to do? Possibly, by being first innovators, first thinkers.

"It is possible that we could fulfil that role, because we are part of that industrial society that isn't here a hundred years from now, that's transitioned to something else. Yet we are at the end of the supply chain. So it must occur to us first that the future isn't the past.

"Therefore we start thinking before everyone else does ... We give ourselves the mission to change course before anyone else."