In the book Māori Love Legends, from the 1920s, the author Marieda Batten tells the story of Hinemoa and Tutanekai in verse.

"She is a chieftainess royal and I, though a chief, am but baseborn;

"Yet here I dream on Mokoia, dream she is mine, only mine".

The well-known love story ends happily, after Tutanekai’s skill with taonga puoro helps to overcome the distance between the star-crossed lovers. Hinemoa proves a remarkable wahine toa, completing an epic swim to Mokoia island — in the middle of Lake Rotorua — to be with her beau, and it all comes to a steamy happily-ever-after in a hot pool, known still as Waikimihia.

But it is not always so. As the bard would have it, "the course of true love never did run smooth". In that case, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the father’s opposition is the issue.

Indeed, familial opposition was a problem for Hinemoa and Tutanekai too.

And for a tragic love story connected to Puketeraki, here in the South, there is also no happy ever after — unless enduring fame in the landscape is somehow a substitute.

For the couple in this story, the disapproval of their respective families was an obstacle too high to overcome.

It may be factual, he allows, but on the other hand its purpose might might be more about communicating the expectations of parents to their children — elders passing on a message to younger people.

Pakiwaitara, as opposed to pūrākau, tend to be the less formal, more everyday stories of te ao Māori.

But, that’s not to suggest they were without purpose.

This one begins at Puketeraki, where a beautiful young woman lived with her hapū, her family.

One day, Ellison says, another group was passing and among them was a young man of a similar age.

"And so, one caught the other’s eye and they, in time, felt that they fell in love with each other."

Emboldened by these feelings, the young man approached the father of the young woman to ask for her hand in marriage.

"He was told unequivocally he wasn’t quite of the right ranking for her," Ellison says.

The father’s disapproval was a crushing disappointment, no doubt, but the ardour of the young couple was undimmed, and they eloped.

"They thought they would wait a year and then come back and seek the blessing of the union."

As it happened, during the year the wahine became pregnant and by the time they had set for their return, they had a child.

"Now, as I said, their plan was to come back to their respective parents with this beautiful baby, this pēpi, and they assumed they would be welcomed back because the union between them was blessed by this beautiful pēpi."

To say things did not go to plan is an understatement of Shakespearean proportions.

Time had not dimmed the ire of their parents, Ellison says, there were to be no accommodations.

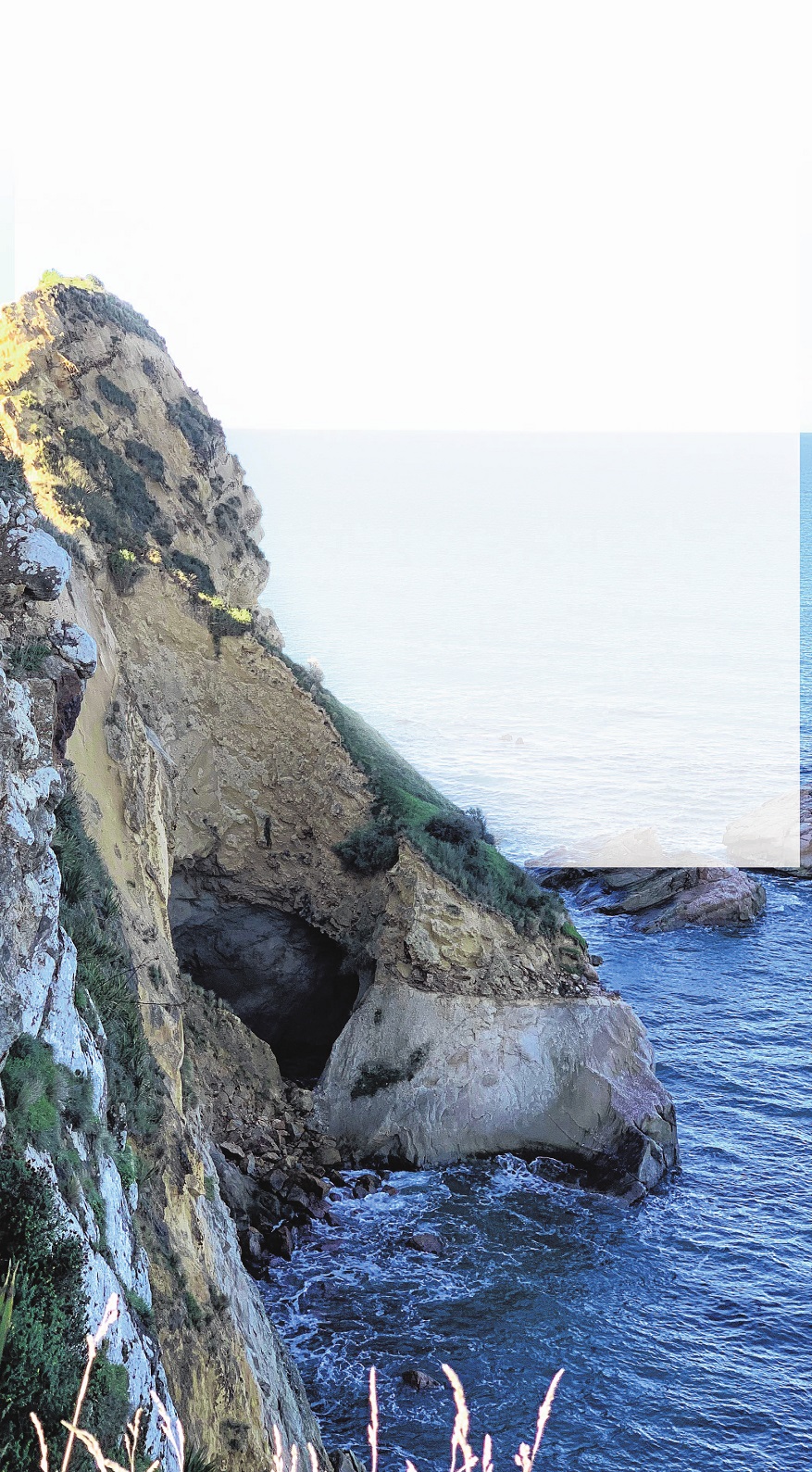

They were taken to the top of Te Pa Hawea hill and cast off a cliff.

"The cliff sits below Te Pa Hawea at the south end of Puketeraki beach."

But in our version, it’s the three of them who are taken to the top of the cliff.

"She was thrown off the cliff and she was responsible for landing on Huriawa Peninsula and creating the first large pehu, blowhole, there," Ellison says.

"The tāne in turn was cast asunder, and he must’ve been a little bit lighter and his landing created the second pehu."

The third pehu, blowhole, gives rise to the question of whether the baby was there or not, Ellison says.

"But it is said that the baby, on being the last one thrown by the parents, landed further away and created the smaller pehu.

"The moral of the story might be to do what your parents tell you to do, or face the consequences of your actions, or that there are always consequences to actions," Ellison suggests.

"So it’s a rather dramatic little pakiwaitara, but I do think it was designed to tell a story and carry that message to younger folk, rakatahi."

And it does offer an explanation for the geographical features, the pehu at Huriawa Peninsula, which juts out into the Pacific just south of the Waikouaiti River mouth.

An alternative explanation for the story’s purpose is that the place, the cliffs, were tapu. A dangerous place might well be considered tapu, he says.

The number of stories in te ao Māori involving frustrated passion and cliffs certainly bolsters that interpretation.

"They might say there are taipō there, goblins or creatures which will do you great harm, so as to keep the kids away from that, tāmariki away from it, with the aim of protecting them."

As for Puketeraki itself, there are again competing understandings.

When he was growing up, Ellison was told Puketeraki means the hill that runs to the sky or reaches to the sky — "raki" is southern dialect for the sky.

However, some say the name should be spelt Puketīraki, Ellison says, with the macron on the first "i".

There is another Puketīraki inland from Temuka (more properly Te Umu Kaha), the fact of which strengthens the argument for that spelling, Ellison says.

If that were the case, the name might be related to cabbage trees, tī rākau, which were an important food source.

"And tī rākau were definitely harvested on the hills here as well. So that might well be a valid version, as well, to ponder further."