They are the echoes of our collective memory.

From the rugged peaks of Te Tiritiri o te Moana (the Southern Alps) to the deep waters of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa (the Pacific Ocean), each Māori name carries within it the knowledge and stories of our ancestors.

That’s why, 12 months ago, we launched the Toitū te whenua: Māori place names project.

Its aim was to uncover the meanings behind some of the Māori place names in the region, both the familiar and the less well-known.

As we might have expected, the work involved engaging with some deep histories, stories of those who have gone before and descriptions of the interactions they had with this whenua and the resources they found here and around which they built their communities.

Rather, they are gateways of understanding, beckoning us to delve deeper into the roots of our heritage.

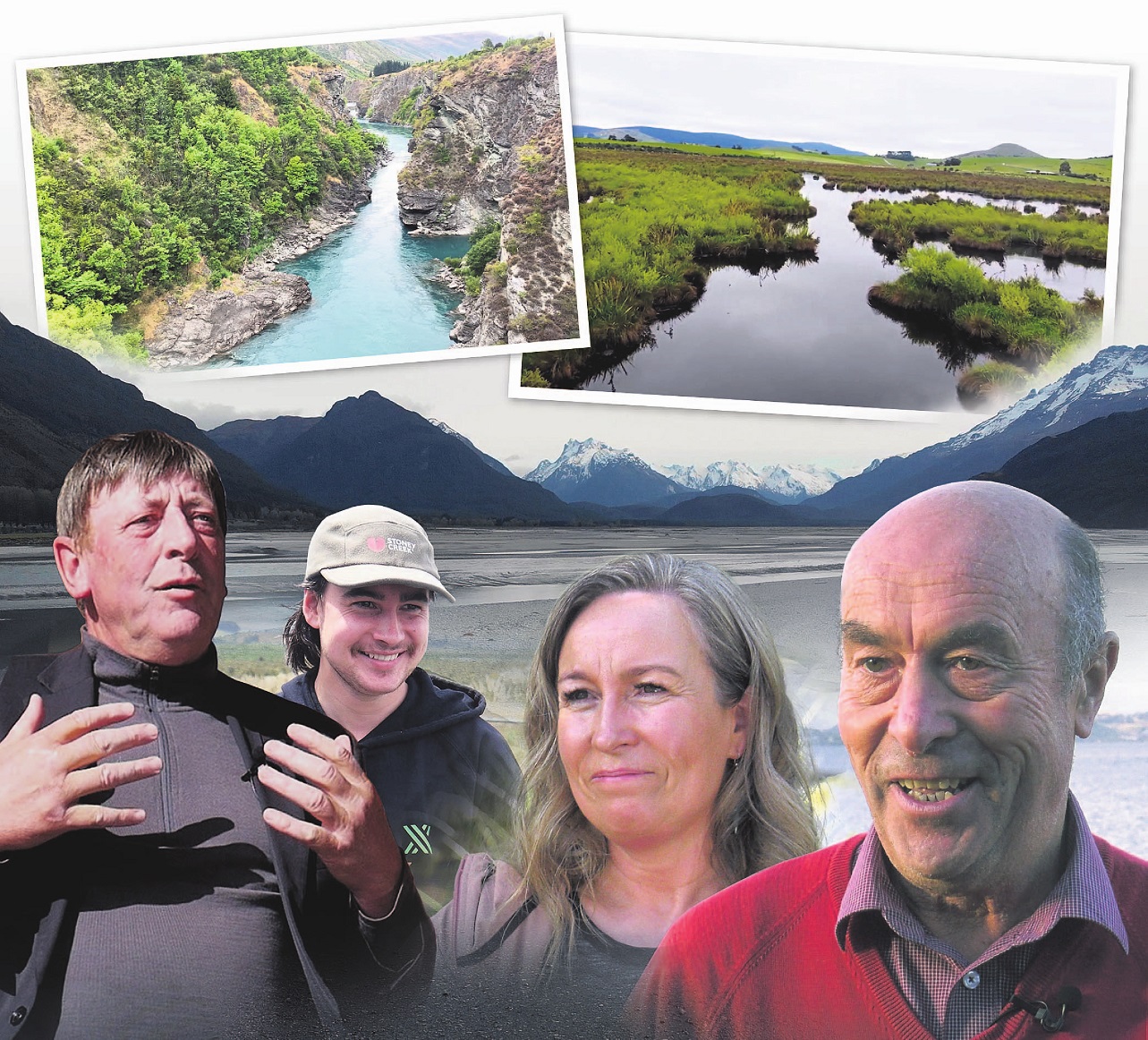

Ōtākou Rūnaka members Paulette Tamati-Elliffe, Tūmai Cassidy and upoko runaka Edward Ellison and Kāti Huirapa Rūnaka chairman Matapura Ellison have been our experts, helping us to understand the depth of Māori place names.

They each are heavily involved in the development of Ngāi Tahu, contributing to its growth and working towards maintaining and better understanding indigenous mātauraka (knowledge).

Much of the mātauraka they shared with us was passed down to them through the generations.

Place names are far more than labels on a map; they are profound markers of identity and heritage.

Tamati-Elliffe says place names are integral to understanding her connection to the past, the whenua (land), and her identity.

"It’s where we come from, who we are, the whenua — without the whenua, who are we?" she asks, emphasising the deep-rooted bond between people and the land.

"Place names are like records that store knowledge of historical events, prominent figures and features of the land, water, plants and wildlife," he explains.

For Māori, these names encapsulate connections to ancestors and sacred sites, food gathering grounds and places of sustenance going back more than 40 generations, he says.

Cassidy says it is "incredibly important" to preserve the integrity of these names, as they are often named after ancestors.

"When we hear people butchering or corrupting the name of our ancestors, it doesn’t sit very well with us," he says.

Edward Ellison describes the intrinsic link between place names and the landscape.

"They are names from antiquity, obviously from our ancestors, with meaning. They tell us about that place, what may have happened there. Some of it is whakapapa-related, some of it related to the creation stories, or mahika kai, clues to what a place may hold in terms of values."

These names bring the landscape alive, he says.

"It’s not just a hill or a river; there’s a story that goes with it in the name — and they’re often quite beautiful names as well."

For those who speak te reo Māori, there is a passionate desire to restore traditional names and afford them the mana they deserve.

Tamati-Elliffe encourages everyone to learn and use these names, regardless of their familiarity with the language.

"Kaua e whakamā [don’t be shy] — give it your best shot. It’s all about attitude and we can certainly know when someone’s trying and they’re open to learning," she said.

Even for descendants of Kāi Tahu who were not exposed to te reo Māori, there is a growing movement to reconnect with their cultural roots.

The fight for the recognition and revitalisation of the Māori language, spanning generations, has brought about the opportunity for current and future generations to rebuild their confidence and understanding.

Ellison highlights the educational aspect of learning Māori place names.

It is not just about pronunciation but about understanding the meanings and stories associated with these places.

"It is a great entry into understanding te reo, understanding the meaning of the place, the pronunciation associated with a place as well, and getting their story," he says.

Ellison says he finds it rewarding when people who do not identify as Māori speak of their mountain or place using traditional Maori names, celebrating the continuity of te reo and the importance of whakapapa.

This journey of learning is a powerful way of being a New Zealander, he says, fostering a deeper connection with the land and its history.

"Travelling up the Pig Root on the main highway, I would recite the names I learned. These names warmed my relationship with my tīpuna [ancestors], telling me stories and giving me clues on what they were doing in these areas," he recalls.

Names such as Te Waipārera and Te wai o Rimurapa offered him insights into the resources and historical significance of these places.

Te Waipārera refers to a place where the pārera duck lived, and Te wai o Rimurapa, is a name recognising an ancestor of his, Te Rimurapa.

For Matapura Ellison, learning the meanings behind place names enriched his understanding of the landscape and his tīpuna.

"It creates a far more intimate understanding for us today, contemporarily, of our landscape, and says to everyone else, these people were here, and these are their ancestors," he says.

Each name we recognise, honours the legacy of those who have walked this land before us.

Māori place names are embedded with knowledge, and that knowledge is a taonga.

As guardians of this taonga, we hold a responsibility to embrace and cherish these names.

They are symbols of resilience, endurance and unity.

Tools such as Ka Huru Manu and Kareao, online portals providing information about place names across the Ngāi Tahu region, make it easier for people to delve into this rich cultural heritage.

Kareao is an online Ngāi Tahu archive of manuscripts, photographs, maps, biographies, oral histories and information on taonga.

Ka Huru Manu is explicitly part of Ngāi Tahu efforts to restore the mātauraka behind place names and correct misspellings.

AS we conclude our journey retracing the steps of Māori in Otago, let us reflect on the significance of Māori place names in shaping our collective identity.

They are not just names; they are the pulse of our tīpuna, beating with the rhythm of generations past.

Let us not shy away from their complexity. Instead, let us embrace the challenge they present.

For in learning these names, we not only enrich our understanding of the land but also embark on a journey of cultural discovery, bridging the divide between past and present, between tradition and modernity, and between two cultures.

When we embrace te reo and Māori culture, we uncover not just the depth of language, but also the depth of our humanity.

Waiho i te toipoto, kaua i te toiroa.

Let us keep close together, not far apart.