Healthcare professionals - nurses, doctors, and a wide range of other health workers - are used to advocating for the health of patients and communities within the health system. We also understand that the most important building blocks for health lie well outside the health system, in warm dry housing, safe neighbourhoods, clean air and water, and a safe, stable climate.

Over the past week there has been deeply disturbing news about record high temperatures in Greenland, causing a major spike of climate-disrupting methane from melting permafrost, which feeds back to cause further dangerous heating. Although this seems very distant from our health and wellbeing here in Otago, there will be literal, as well as metaphorical waves of effect, some of which are already starting to be felt here.

Those of us living in the wider South Dunedin area are experiencing harms to happiness and emotional health. There is an undercurrent of anxiety about when the next record-breaking rainfall, coupled with sea-level rise will flood homes, and perhaps make them permanently uninhabitable.

Like housing, safe drinking water is critical to public health, but this can no longer be guaranteed even in a wealthy country like New Zealand. Warming freshwater even by small amounts means harmful bacteria can multiply more rapidly. This warming is being combined with alternating extremes of dry followed by severe rainfall.

Add to this by putting more cows on each hectare of land, requiring irrigation, and the result is a recipe for large outbreaks of waterborne illness like the 2016 event in Havelock North. In August that year, 5500 people - more than a third of the town - fell ill as a result of Campylobacter in their tap water, with an uncertain number continuing to suffer long-term complications.

While reducing New Zealand's own small proportion of global climate pollution won't protect us from these impacts, we can hardly call on the big emitters, such as the United States, China and India, to ask for their protection through emissions reductions if we aren't doing our fair share. Indeed, as a wealthy country with very high per person emissions, we have an international obligation to show leadership.

To protect our wellbeing, our fair share means strong targets in the Zero Carbon Act for all three of our major heat-trapping gases: carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. The earth system messages we're getting from places like Greenland are loud and clear that we must act urgently, decisively, across all sectors of society, and lead from the top through strong regulatory signals. New Zealand's contribution to treating the sick climate needs to get us to zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2040. We also need to halve our methane and nitrous oxide pollution in the same timeframe.

Methane is especially important for New Zealand. It not only contributes more than 40% of our total climate pollution, but it is a more powerful heat-trapping gas than carbon dioxide in the short-term. Because it is quickly transformed in the atmosphere, reducing methane now can buy us some time as we make the longer-term infrastructure transition to low-carbon. Unlike Greenland, where methane release is about permafrost melting, in New Zealand it is almost entirely about livestock, which means requiring our food production system to shift.

Strong targets, and the action required to meet them don't have to be a cost, even though we're often spun that story by those who are worried about their own profits. Increasingly, countries that have been showing leadership in reducing emissions are finding that investments in clean energy, low-carbon transport and climate-friendly food systems are already reaping gains for their physical, mental, social, environmental and economic wellbeing. Reducing livestock methane through a shift from cows and sheep to more plant production can be one of those sources of multiple benefit.

The benefits of shifting back from growing milk powder as a global commodity towards the more diverse, plant-based production that characterised places like Otago only decades ago would have a positive influence on New Zealand diets and our health. By putting wellbeing and fairness into policy design, the advantages would be tangible in the short term.

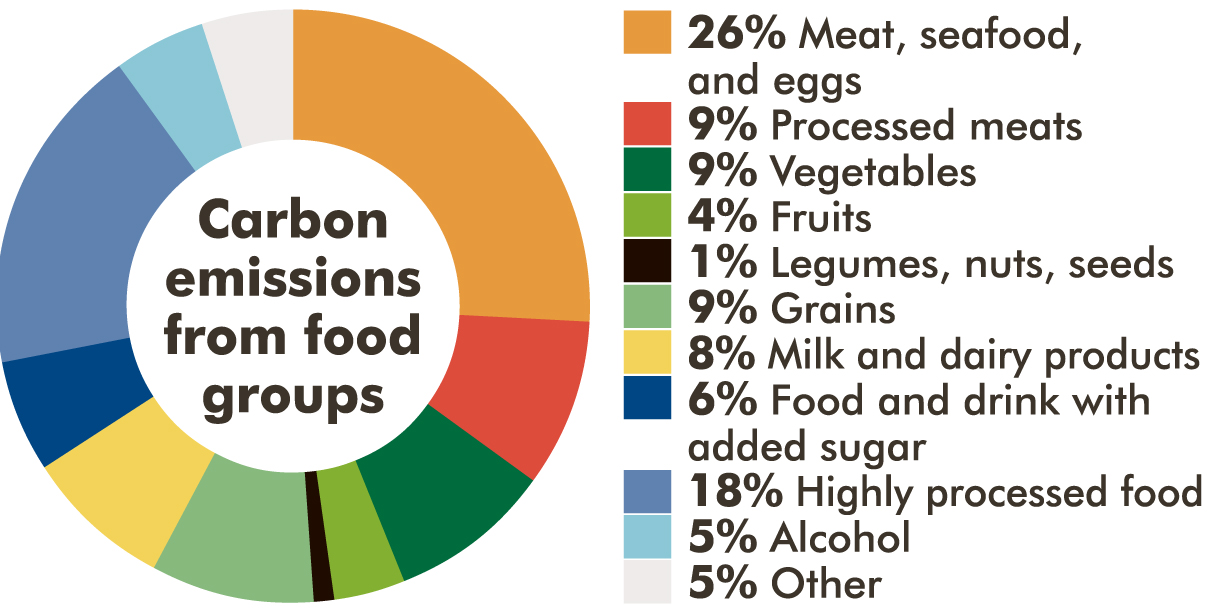

We can enhance our ability to feed all our communities in an affordable way, even in the face of economic and climate-related shocks. We have a chance to fix the critical state of our rivers, lakes and drinking water sources, caused by increasing amounts of cow waste and fertiliser run-off. And we can make inroads into some of our most troubling health issues, such as cancers, heart disease, diabetes and obesity, by adopting an approach to eating that is plant-based, with less meat, dairy and highly processed foods (which are also carbon-intensive).

We can also address the debt crisis our farmers are facing through over extending into industrial equipment and expensive inputs. As the dairy industry has expanded and intensified, so too has farmer debt, rising from just over $10 billion at the turn of the century to six times that this year, prompting new legislation to be passed this week providing extra support for farmers in financial distress.

Because much of the meat and dairy we produce is exported, it's hard to see how what we eat can make a difference. But our collective food choices send strong signals to food producers about the unacceptability of current environmental and health harms. What we choose to eat is influential for the health of the climate, as well as being critical for our own wellbeing.

Recently, research at the University of Otago estimated the benefits for the climate and our health if the New Zealand adult population changed our diets from the average lots of meat, dairy and highly processed foods, towards healthier plant-based foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds.

We found large benefits from such a shift, especially when it was coupled with reducing the amount of food we waste unnecessarily. Depending on how much we are willing to change, we could not only cut our dietary climate pollution, but also save more than $20 billion in healthcare costs over our lifetimes.

Caring for our wellbeing means advocating for a successful Zero Carbon Bill with strong targets for all our climate pollution, including agricultural methane. Health and fairness need to be at its heart. When we shift from seeing this as a cost, we can open up the biggest opportunities for health this century.

It is crucial that the Government hears about the effects of climate change in our lives, the changes we are already making, and the opportunities we see for wellbeing in climate action, by having a say on the Bill and encouraging others to do the same. Submissions are open until July 16.

Alex Macmillan is a public health physician, senior lecturer in the University of Otago Department of Preventive and Social Medicine and co-convener of OraTaiao: NZ Climate and Health Council. Each week in this column, one of a panel of writers addresses issues of sustainability.

Make a submission

Submissions are open on the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Bill - otherwise known as the Zero Carbon

Bill - until July 16. To make a submission go to https://tinyurl.com/y6ons3sp.