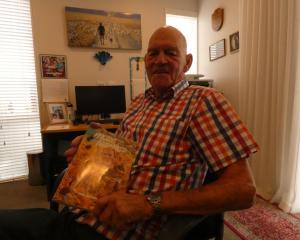

The self-admitted numbers man keeps a close tab on everything going in and out of the family’s Brockworth Partnership farm run by him, wife Ruth and son Joe.

"It’s probably in our DNA really. There’s many different ways you can farm even down to the timing of shifting animals and little things can make a difference."

That explains the decades of spreadsheets on the performance of their cattle herd and sheep flock that fill up his computer.

His records go back to 1990 for weight gains with the sire and dam identities logged in for tagged calves and records maintained of their performance beyond weaning.

"I was thinking the other day it was quite easy to do that as we only had 120 to 150 cows and we’ve got a few more than that now," he recalled.

"So it does take a bit of time pairing the calf up to the cow but it’s something we enjoy and there’s value in being able to follow that animal past weaning knowing its breeding and how its performing. We’ve been able to do a lot of production culling over the years and are probably at the stage now there’s not a lot more to do because we don’t get a lot of tail-end animals any more."

Proof of this wisdom is they only had four dries from mating 300 mixed-age cows.

To put that into context, the national average for getting cows in pregnancy is probably close to 80%.

Mike said they still had the odd outlier that did not perform, but this could often be put down to weather conditions or their management than a genetic fault.

"That’s one of our better results, but we generally don’t get too many empties. We’ve actually got the rams out with the ewes at the moment and it’s the same principle — the idea is you give the ewe the best chance of getting in lamb by a ram and you do the same with your cows. You don’t want to put them in a big expansive paddock and try to have them in mating-friendly paddocks and you get less bull breakdowns that way and better coverage as well. We keep a close eye on things at mating time."

Even the best laid plans, however, can go awry, he said.

"I found one newborn calf once 400m down the hill from where the cow was and it wasn’t a particularly hard paddock — she’d just gone under the fence. The cow was standing up there and I could just see a slimy trail because they’re so slippery when they come out and I could see way down the track a calf by the cattle stop basically halfway down the hill. I went down, picked it up and brought the calf up to the cow and they were both happy."

The odds of this ever being repeated are unlikely as their pregnancy scanner tells them now if their cows are early, normal or late after measuring the foetus. Those with earlier conception dates can go in the flatter paddocks and the later mothers can go in steeper paddocks until they are due.

Today Brockworth extends over medium to steep hill country between Little Akaloa and Decanter Bay. Mike’s father bought the original farm in 1965 which before then had been owned by four generations of the Kaye family.

The property had expanded from 380ha to 430ha before Mike took it on in 1983. A couple of neighbouring blocks were added in the 1990s and in 2007 the family took the opportunity to lease a nearby property to add another 450ha to their 520ha base. The home block now goes from sea level to 500m and another 139ha block they bought above Little Akaloa rising to 750m has reduced the risk of the property going summer dry.

A range of growing seasons from the front of the farm to the rear has given them more options for shifting mobs. Another block bought in 2016 in Little River is used for finishing beef cattle — often heifers they do not want to mate — from November to the end of April.

They have toyed with summer and winter crops, but the dryland farm revolves around pasture growth, with extra baleage brought in most years when it is dry.

When the first Williams set foot on Brockworth just few cows of a wild nature shared company with traditional Romney ewes. The ewes were carried at a high stocking rate as a result of the Government’s Stock Incentive Scheme which bemused farmers quickly deemed the "Skinny Sheep Scheme" because they were virtually told to stack up farms at the expense of their performance. Perendales joined the Romneys and were crossbred to Romdales for a while before East Friesians arrived in the 1990s. The fertile new bloodlines sent their lambing rates from 100% to 150%.

Prior to that they would sell all their lambs at weaning to the works averaging 11kg carcass weight.

That was an eye-opener for Mike on the importance of genetics. It was a time when he became involved in farm programmes and got off the farm more often to see what other farmers were doing.

"You realise actually we could lift our game quite a bit and we did and there’s a lot of good farmers on Banks Peninsula now that are actually performing really well."

Today the flock is a Texel and Romney composite with an emphasis on producing a meaty animal.

The move from his father’s commercial Hereford herd to Angus cows can be traced to an experimental phase dovetailed with the arrival of weighing scales on the farm.

This sparked a recording interest long before most commercial farmers grasped its significance.

Mike said he learned a lot from weighing cattle and trying to find out why some animals put weight on and others did not.

At that stage he was buying calves from different breeds to work out which ones were doing the best.

After the 1988 drought produced a lot of empty cows they wanted to build numbers up quickly so decided to mate the yearling heifers.

"I put a hereford bull over them. [Angus stud breeder] Tim Wilding said ‘you don’t want to do that, I will lend you a bull’. It was an ugly looking thing but had good birthweight so we used it and the progeny were quite good so I ended up buying it and buying another bull and using it. It was probably a bit of hybrid vigour, but these animals were doing better so there was a bit of a message there."

The results told him it was time to move on to an Angus herd and the breed remains on the farm to this day.

Angus suit their needs with strong branded programmes attached to the breed and the hardy animals cope well on their sometimes steep terrain.

"The cattle are what we are passionate about — the sheep are just here to pay some bills. Our cattle operation performs equally well as the sheep and we have a good sheep operation as well."

This season they are mating 465 cows and heifers. Not all of them will be kept with some in-calf heifers sold already and only 70 replacement calves to be retained.

Keeping close records of the cattle for so long comes in handy as they run 14 mating mobs on the various blocks. Four of the mobs are heifers and there are a couple of first-calver mobs as well as seven groups of mixed-age cows and a late mob.

They put three to four specialist low birthweight bulls over the heifers in early November for six weeks with the rest of the bulls being main herd sires that go out with the cows from mid-November for nine weeks.

Pre-weaning weighing sessions are followed by a further dusting of the scales at weaning. Sometimes this shows them how little weight they are putting on calves in the later stages of leaving them with their mothers.

This can point them to an earlier weaning if conditions are right as they often struggle for quality feed in late summer.

The risk of drought is always around the corner at Brockworth and a lot of baleage had to be brought in a few years ago when rain failed to show.

They were lucky to also get grazing on a paddock next door which allowed them to retain a lot of breeding cows after selling most of their steers.

In average seasons they like to sell some of the steers before their second winter at 15 to 16-months, often to Five Star Beef feedlot near Ashburton from November to January.

Often they take cull heifers through to 300kg carcass weight so if conditions do get tight they can quit them early.

This acted as a buffer to protect their cow herd, Mike said.

Every season is different, but often half of the lambs are finished for the freezing works and the other half go as store stock to other farmers.

For the beef herd there is more flexibility with surplus females finished on-site and the steers often sold at 500kg liveweight to the Five Star, its grazers or other finishers, while the calves also act as a cushion if conditions run to drought.

The Williams’ eye for details explains why the family is one of 10 commercial farmers to join a nationwide programme — funded by Beef+Lamb NZ (B+LNZ) and the government — to lift the genetic results and income of beef cattle farmers.

The seven-year Informing New Zealand Beef programme also wants to develop a genetic evaluation for comparing bulls of different breeds for more efficient, profitable and lesser-emitting beef animals.

An estimated breeding value for cross-breeding has piqued the interest of the Williams.

They are also considering the offer by the programme to gene test their heifers. Progressive stud breeders are already using the technology to predict the genetic potential of an animal based solely on its DNA.

They overlooked it this year because they already record birth dates for gestation length and already identify the parentage by recording the sire and dam at mating time.

But they can see the value of a genomic test which gives greater accuracy to identify animals with desirable traits than estimated breeding values.

This could be useful for traits such as intra-muscular fat, net feed efficiency and days to calving.

While they have been recording weaning weights and removing lower performers for a long time, they have only lately been recording the physical performance of their animals.

They credit the Informing Beef programme for coming to grips with condition scoring.

A B+LNZ genetics operations specialist came out to give them a hand in late January during pregnancy testing and condition scored the cows the first time on a scale of 1-10.

The cows made scores of six to eight for an average of seven, while they were also scanned to see if their pregnancy was early, normal or late.

This was followed up by Joe taking on the condition scoring the next time and his results lined up with the previous scoring. Also pleasing was that most of the cows had maintained their numbers.

"This is something that we’ve got out of the programme," Joe said.

"The idea is we want to give a condition score on the cattle beast and also a weight and match this with the weaning weight from the calf. With that information we can work out the consistency of the animal. If they’ve hopped on the weigh scales with say a high condition score of eight and they’re quite heavy and then they’ve either produced a poor or a good calf then all those have reasonable bearings on whether to keep that animal going forward or do we want to sell it."

Mike said putting the condition scoring data into the mix would be useful for guiding them before mating, such as putting lighter condition cows to more of an "easy, doing-type" bull.

That would also help them work out the genetic potential of each animal.

Joe shares the same deep interest in cattle recording and estimated breeding values as his father with both of them working on or with Angus studs.

"Joe’s got a good handle on technology so he’s introducing me to a few new ideas in simplified recording. We are doing EID recording on cattle now."

Joe had previously worked for the Ministry of Primary Industry’s mycoplasma bovis team and saw first hand the value of electronic tags.

"When I came back here one of the things I got quite frustrated with was reading the visual tag when we would go to weigh the cattle beast. The older the cattle beast gets the harder it is to read. I just said to Dad we would earn that money back on the Tru-Test indicator pretty much within the first couple of sessions which we would spend in terms of hours spent weighing. It took a bit of convincing and a couple of sessions and basically now I’m the one when we do weighing that has to look after the indicator screen while Dad does the scanning. The screen brings up the animal and a record of its previous weight immediately while we’re there."

Mike has the software on a cellphone app and can simply airdrop the data to the computer.

"It’s sped things up remarkably in terms of weighing," Joe said.

More lately, they have started to give their calves a docility score to give preference to good-natured calves in another initiative that came about by being involved in the programme.

The advice they have got from their programme contacts is to do this scoring at weaning because the cattle have had the least handling then.

They are also interested in the new estimated breeding values for net feed efficiency that have come to play.

Mike is not a great fan of wasting time trying to get stragglers up to the quality of top-line animals.

"By having the weight of the calf you’re actually evaluating this and it’s a pretty easy decision if she’s a light cow and a poor calf. But if she’s got a good calf then you think how much extra feed is that good calf worth and you have to weigh up whether you want that in your system or not. Different people come up with different answers I suppose."

The bottom line is if they do not perform, they go.

He said most sheep and beef operations had cows for cleaning up rough pasture following the sheep so easy-doing cows that could handle the conditions were valuable.

On top of that they needed the genetic credentials to produce a good calf "as heavy as possible", he said.

While reluctant to set limits, they were pleased with selling seven-month old steer calves weighing 280kg at weaning in early April last year.

One of the reasons Mike put his hand up for the programme was to get his son more involved with different farmers and other ways of thinking.

This worked well for him when he was involved in farmer councils and picking up little tricks of the trade at field days.

They hope to get more detailed information back from the programme’s other commercial farmers to view other results and see this as its main challenge.

What matters most for them, however, is how their own cows perform on their property.

"We think we’ve got quite a good herd of cattle now, but how do they stack up against other herds? Are we doing the right thing? Knowledge is power I suppose."