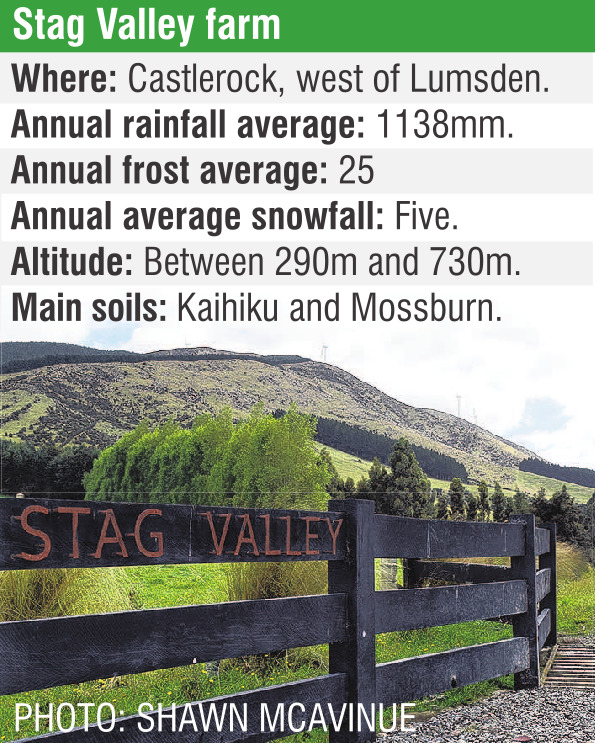

Stag Valley owners Simon and Annabel Saunders hosted a Beef + Lamb New Zealand farming for profit animal health day on their farm in Castlerock, near Lumsden.

When Mr Saunders’ parents established the farm from 550ha bare land in the mid 1960s, they "chucked up a boundary fence and bought some stock", he said.

Now the farm was about 1400ha, comprising about 60% cultivated paddocks and 40% rolling to steeper tussock hill country.

About 130ha , which could not be cultivated, was small blocks of forestry.

A wind farm operated on the property, making the most of the strong winds which roared down the valley.

The trees helped slow the wind and workers to keep their hats on, he said.

Four QEII covenants had been established on the farm.

"Like any farmer we want to leave the land in a better state than when we took over," he said.

About 10,500 stock units were run across about 1250ha effective.

Sheep included more than 6000 Headwaters ewes and their replacements.

Stag Valley manages the Headwaters breeding programme, which includes 1350 Headwaters elite ewes and their replacements and 1000 multiplier ewes, and it was a big part of the farming operation.

About half the lambs were finished as Lumina lambs and the other half were sold store as Lumina finishers, requiring 35 days on red clover and chicory.

Mr Saunders praised the sheep-finishing work of Stag Valley manager Allen Gregory.

"Historically we haven’t been very good at finishing but when Allen arrived on the scene eight years ago and we got heavily involved with Headwaters, we really focused on finishing and we are a lot better at it now."

The beef cattle were a mix of Angus breeding cows and finishing cattle.

Beef steers were bought at calf sales and taken through to yearlings to sell to a Five Star Beef feedlot.

About 250 dairy heifer calves arrive in December and stay for 18 months, leaving at the start of May, returning to their dairy farmers.

A goal on Stag Valley was to produce high-quality stock, while trying to minimise animal health inputs as much as possible.

While the main business was sheep, cattle played an integral part in the system.

Vet Trevor Cook, of Totally Vets in Feilding, developed an animal management plan for Stag Valley about 10 years ago and refines it annually.

A key focus was to maximise livestock performance.

Dr Cook said many drenches were no longer effective on most farms in New Zealand, despite him warning farmers of the issue for the past 30 years.

"We have seen a massive rise in the last five years ... as long as we use a chemical as our main tool for controlling a parasite, the parasite will always find a way around it," he said.

If farmers managed worms better they could grow their lambs 30% faster.

"It has nothing to do with drench, it is purely how we manage our grazing systems," he said.

A lamb provided a high-energy diet could cope better with a worm burden. Lambs deficient in copper, selenium and cobalt were less able to cope.

A lamb with a worm burden could appear healthy but its appetite would be reduced.

"There is massive, massive production cost that we don’t see because the animal is not eating as much," he said.

A lamb requiring frequent drenching was not able to reach its potential for liveweight gain.

Any system running big mobs of lambs was a "parasite paradise".

A standard farming practice was to wean lambs to paddocks contaminated with worm larvae.

"As soon as they are in that system their liveweight gain drops ... think about what you can do now to have different grazing options when you get to weaning next year," he said.

Calves younger than 10 months old were also worm contaminators.

Cattle and sheep did not share worms and adults of both species were not contaminators, so grazing management could be used as a tool to limit the exposure of young stock to parasites.

Mature worm larvae loved cold conditions and could survive a southern winter and live on grass for months. They did not like the dry or the light.

The larval cycle could only occur on grass and could not happen on crops such as chicory or summer rape.

"If we can have a system with no grass, we have no worms," he said.

A faecal egg count would reveal the extent of a worm challenge and set expectations on drench frequency.

A 28-day faecal egg count provided the confidence to extend the drench interval.

Vet Andrew Cochrane, of NSVets in Riversdale, said farmers should think of vaccines for livestock as an insurance policy.

"What level of loss, or risk, are you comfortable with?" he said.

No vaccine was 100% effective but costs were often outweighed by benefits.

He considered a toxoplasmosis vaccine to be a "no-brainer" because one shot could protect a sheep for life.

Every farm had the disease present, Dr Cochrane said.

"You’re dreaming if you don’t believe your farm has wild cats."

A clostridial vaccine was also a "no-brainer".

For the vaccine to be cost effective, it needed to save the life of one lamb in every 400 vaccinated.

Another "no-brainer" was vaccinating all bulls every year for the bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) virus.

A decision on vaccinating female cattle for the virus depended on a farmer’s risk appetite and biosecurity gaps.

The losses from the virus had been significant, including 30% empty pregnancy scannings.

"There are huge calf losses as they are born weak or stillborn. I have been in situations where there were more than 50% losses in calves to market as a result of BVD," he said.

Sheep and beef farmers needed to ensure mineral levels were optimal and provide four of them to their livestock.

Sheep needed selenium, iodine and cobalt (B12).

"Whatever we are doing for our ewes, we should be doing for our rams too — the rams often get neglected and forgotten about," he said.

Cattle needed selenium, copper, plus or minus cobalt.

"If in doubt, test. We have the ability to test for all these minerals to get an idea on what is happening on your property."

Well-fed livestock in good condition were critical for a healthy, robust immune system.

"Ensuring your sheep don’t spend too much time under pressure and are well fed goes a long way to minimising your animal health costs," he said.