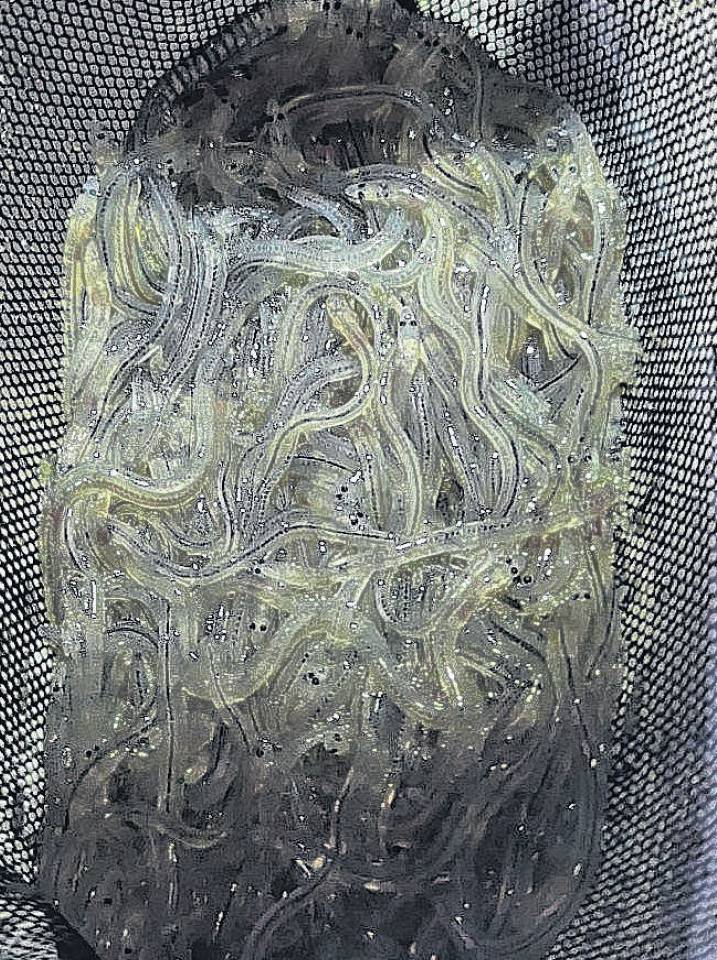

Glass eels, the first life stage of freshwater eels, have captivated several experienced fishermen tasked with corralling these transparent thread-like animals, all in the aid of science.

The fishermen from the Ashley Fisherman’s Association were called on by Jack Wooton, a visiting PhD student from the United Kingdom.

Jack, who is being hosted by NIWA Christchurch, is carrying out research in New Zealand focused on freshwater eels.

He wants to improve protective measures at extraction points on rivers so the glass eels are not sucked up and killed before moving up river to become elver and, eventually, adult eels.

‘‘I carried out part of my work on the European eel and have been lucky enough to come to New Zealand and also study your species.

‘‘I am focusing on the glass eel life stage of freshwater eels, which is the first life stage we see coming into freshwater.

‘‘This is the smallest stage that could meet abstraction infrastructure, so understanding how they interact with these areas is key for their protection,’’ Jack says.

‘‘As these animals are nocturnal and like big tides and the right moon phase. This can be tricky,’’ he says.

Enter the Ashley Fisherman's Association.

With local knowledge of the area, a small group of fishers helped source the eels needed.

They used specially adapted nets (under licence) and fished at dark on a new moon tide, to source the eel.

‘‘After two fishing trips we had all the eels I needed.

‘‘This would not have been possible without the help and knowledge of the fishermen.

‘‘The local knowledge provided by this group has enabled this scientific study to go ahead.’’

The fishermen say the hard part about catching the glass eels was they only came in on the incoming tide during the night or early morning when it was ‘‘really dark’’.

The Department of Conservation gave the project its blessing, granting special rights to fish in the night to catch the ‘‘baby eels’’, the fishermen say.

‘‘As the tide started to come in, we started to slowly catch some of the eels.’’

The fishermen, some in their 70s, were keen to go again, so with DoC’s permission a second night’s fishing was held.

‘‘So we had our second night back at the river. The low tide was at about midnight. It was very dark, drizzly, and cold, but we had a good night and Jack headed back to base in Christchurch at about 3.30am with the catch,’’ the fishermen, who now consider themselves ‘expert glass eel catchers’, say.

Jack has set up a simulated river flow machine at NIWA, in Christchurch, designed to see what sized screen can stop the glass eels in an endeavour for industry and nature to work side-by-side.

He says this will give the tiny thread-like glass eels a better chance of survival, allowing them to grow into adolescent elvers and eventually adult eels further upstream, where they can live for years.

To date he has determined they can get through to 1.2mm, where the mesh runs vertically to allow weed and other material in the river to wash down and off the screen.

Freshwater eels have an unusual life cycle which sees them travelling between the ocean, estuaries and freshwater.

They only breed once at the end of their lifecycle, migrating thousands of kilometres into the Pacific Ocean, near Tonga, to release eggs and sperm in a process called spawning, before dying.

The fertilised eggs then develop into larvae called leptocephalii, which travel back to New Zealand via ocean currents.

Eels then enter river estuaries as small juveniles, known as glass eels, and can spend a year or more in the estuaries before migrating upstream, becoming darker and commonly know as elvers.

The adult tuna live for a relatively long time in rivers, lakes, wetlands, ponds and streams, eating and preparing themselves for when they are ready to begin their migration back out to sea.

When the migrants or tuna heke are ready to begin their long migration, some of their features change to help them on their journey.

Their heads become bullet-shaped, their eyes enlarge, and their fins get larger and darker to help them on their journey in the depths of the ocean.

Longfin eels are endemic to New Zealand, and are the largest freshwater eel.

The other eels found in New Zealand are the native shortfin eel (Anguilla australis), also found in Australia, and the naturally introduced Australian longfin eel (Anguilla reinhardtii).

Longfin eels have the same migration pattern, are good climbers as juveniles and are found in streams and lakes, a long way inland.

They are an important traditional food source for Māori.