McMillan has since returned to the New Zealand Army and is today Lieutenant Colonel Grant McMillan. He is based in Burnham.

The first national commemoration service to acknowledge the deployment was held recently in Wellington, prompting many recollections for McMillan and fellow service personnel.

It had been the first deployment for McMillan, who was still working in education at the time and took leave as an army reservist.

‘‘As a reservist, deployment comes with the job. In a perfect world, it’s the sort of service that is never needed. But when these skills are needed, it’s good to know that we have good people, who are well trained, well resourced, and well prepared,’’ McMillan said.

‘‘Walking on the moon would be how I described my first impression of landing in Timor. The extent of the damage, the sights and smells of a tropical setting, the broken houses and dozens of people and children walking, but smiling and waving to us as we drove past,’’ McMillan said.

The multinational peacekeeping force had been launched in the wake of violence and widespread destruction from pro-Indonesian militia.

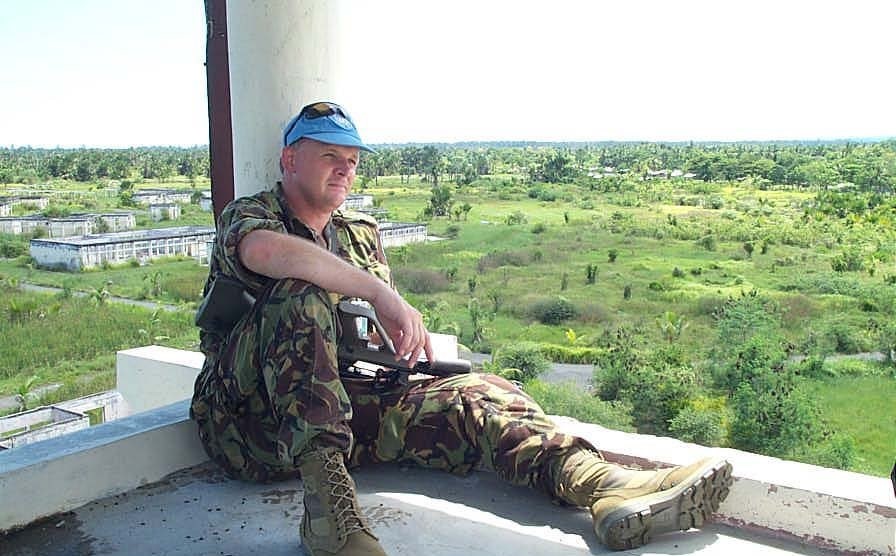

‘‘The Indonesian military had the attitude of ‘my bat, my ball’. As they left Timor following the vote for independence they stripped, and I mean stripped, everything they could take – windows, roofs, equipment, desks and supplies.

“The Timorese were left with shells of their homes, businesses, schools, medical centres, and their large agricultural college for instance,’’ McMillan said.

The international response was also about security, and ultimately moved to nation-building.

‘‘The New Zealand Army mechanics workshop trained a small number of local people in how to repair and service engines. When these trainees graduated they were also each given sets of tools funded by the British High Commission.

‘‘One set of tools to start their own business, and another set so they could teach someone else the skills they had learnt,’’ McMillan said.

While they routinely worked hard and long hours, soldiers also had times where they could relax and have fun. On one Sunday afternoon, McMillan learned about the perils of always trusting one’s mates.

‘‘We had gone to one of the local beaches to cool off. We always went in small groups. The group would swim, while at least one soldier would watch out for crocodiles, usually sitting on the bonnet or roof of the vehicle with their rifle.

‘‘My friend Scott and I were enjoying ourselves when between us we noticed a long dark shape. At first we thought it was a log, then it seemed to flick its tail. I’m convinced we both we ran along the top of the water as we raced to the shore.’’

McMillan said overall the experience of serving in the Southeast Asian country, had been ‘‘life-changing’’.

‘‘Initially I saw the destruction and the disadvantages that the Timorese had all around them, and I wondered how they as a people, or East Timor as a country, would ever move past this.

“However, the local people were talented, creative, and focused. They were the same as us, the only difference was that they had been plunged overnight into poverty and subsistence living, and all the safeguards of civil society had been removed.

“I learnt how fortunate and lucky we are in our society and communities that we live in.’’

‘‘I think even today we can quietly now look back on a job well done,’’ McMillan said.