It’s the first large heritage building people see when they drive into downtown Lyttelton. It’s also the first significant reminder of the Canterbury earthquakes’ lingering effects.

If the barriers don’t make it clear enough, it doesn’t take long for passers-by to see how badly damaged the building was during the quakes that started a decade ago this week but which were most damaging in February, 2011.

There are cracks seemingly everywhere on the category 2 heritage building, bits shaken off and lost entirely, and some of the concrete walls are in a worse state than the others.

The north wall is bowed and leans markedly to the south, and the south wall does the same. The west wall is tied back to the building when it started to separate after the February 22, 2011, earthquake.

Temporary securing work has helped the building maintain its shape for nearly 10 years.

All its chimneys were severely damaged. The western chimney was removed after it collapsed, the area covered by plywood. The eastern chimney was damaged and the fireplace partially collapsed into the old bar.

Wire securing ropes burst through internal walls and ceilings to hold the building together.

Cracking and failed internal spouting and flashings means rain water has been getting into the building for years. Rot and borer have ravaged the ground flooring and bearers.

Later, in 2013, sewage burst through the ground floor during pipe repairs on the road.

Much of the damage is detailed in an “assessment and repair options” report by Structex, which also notes previous work that says repair and strengthening may be uneconomic.

EQC and a private insurer have already determined the building will be uneconomic to repair. A low-end estimate in 2014 suggested it could cost more than $3.3 million.

It was also estimated retaining the facade would add another 40 per cent to the overall cost of a new building.

The company’s demolition application shows it looked to source funding from the council’s heritage trust in 2012, but was told the building did not likely meet the criteria. A bid to get a rates rebate in 2015 also failed, and led to a court case.

With all this in the background, building owner Mitre Holdings believes retaining the external walls will pose enormous challenges and that retrofitting earthquake strengthening work would further destroy elements of the building.

The work needed would be expensive – likely more than the cost of a new building – and according to a heritage impact assessment, would reduce the new-look building into a replica of its former self. For the company, demolition is the preferred option.

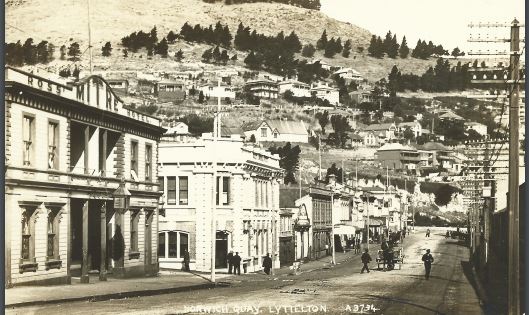

The city council’s heritage assessment of the site shows the Mitre Hotel site has been vacant before. The first Mitre Hotel – considered the first hotel in Canterbury – was built on the site in 1849, only to burn down in 1925.

Its replacement burned down in 1926 to be replaced by the current hotel.

It was built by Charles Percy Cameron, whose family had owned the hotel since 1878. Whereas the old was built of timber, the new one was made of brick and reinforced concrete.

It had to be: the licensing board said it had to be made of permanent materials.

It was about the same shape as the old hotel, but adopted many of the hallmarks of the early art deco period including the elegant curved balcony, balustrades and arches on the facade.

Inside, finishes in the ballroom, the stairway and in the upper hall were also considered significant elements from the time.

But the interior finishes have not survived as well as they could have – many were removed when the ground floor was modernised in the 1970s and some features on the first floor were destroyed in a fire in 1942.

A council heritage assessment prepared in 2015 says the hotel has architectural and aesthetic significance as an interwar hotel that followed closely the appearance of the hotel it replaced.

It has technological and craftsmanship significance as an example of monolithic concrete construction and detailing from a period in which such construction was not widely used.

It also has cultural significance: it was one of only two remaining hotels that could trace their origins to the 19th century, albeit in a different form. The other is the British Hotel, on the corner of Oxford St and Norwich Quay.

The original Mitre Hotel was the first port of call for many early settlers arriving in Lyttelton, and is frequently mentioned in autobiographies reflecting on the 19th-century.

Major Alfred Hornbrook opened a sly grog shop called The Mitre in 1849 while squatting on the current hotel site. The site was shared with a boat and sail-maker. The next publican secured the formal lease for the land.

The first hotel building survived the great fire of Lyttelton, in which two-thirds of the town was destroyed, in October 1870. It was saved using the “fermented contents” of its cellars. It was destroyed in a fire five years later.

Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott had his farewell dinner in the second hotel’s ballroom in November 1910, before leaving on the ill-fated Terra Nova expedition.