He had been keeping a rough tally of the figures after his conversations with employers who had laid off staff.

‘‘The difficulty is that until the [Government’s] wage supplement ceases, you’re not really going to know who’s got a job, going forward, and who hasn’t.

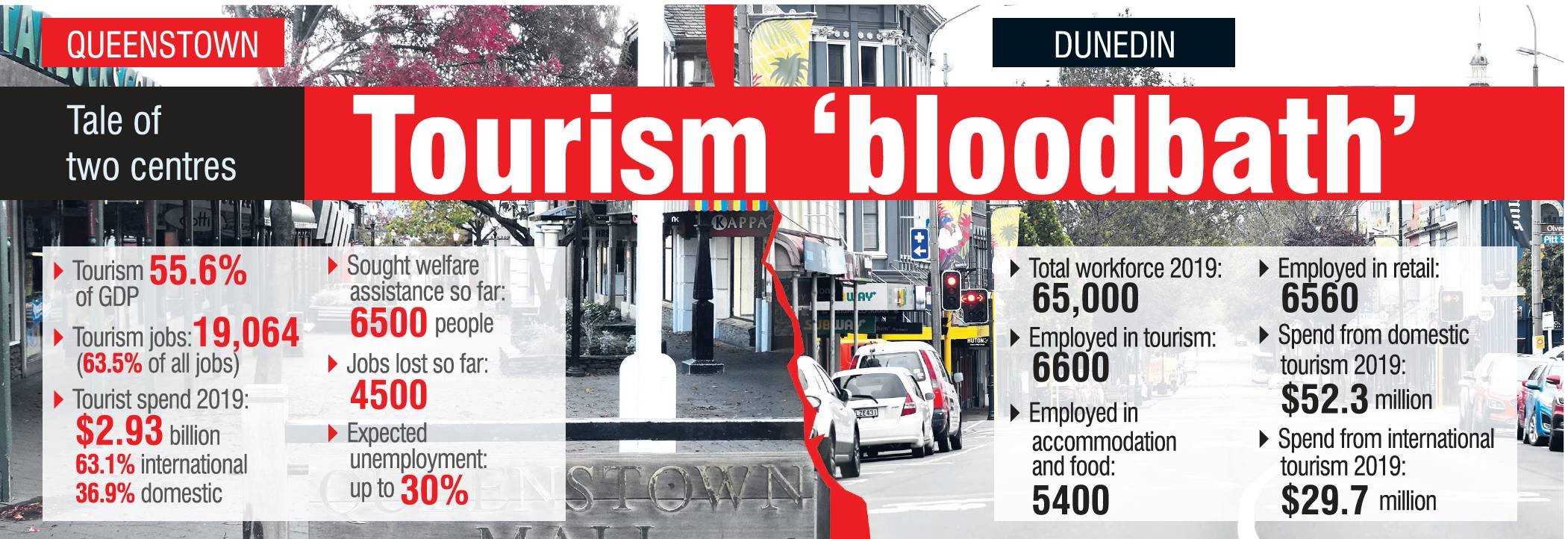

"The reality is business in Queenstown - no matter what you’re doing - is going to be a bit of a bloodbath for a while.’’

‘‘I would suspect we’re looking at 25%-30% unemployment.’’

Some layoffs were the result of businesses going under, others from businesses ‘‘necessarily downsizing’’ to survive, he said.

About 6800 people had registered with the council’s emergency operations centre, which had provided about $600,000 worth of grocery vouchers so far and was referring applicants to social service providers for other kinds of assistance.

The council had asked the Government to provide them with social assistance.

‘‘If we don’t ensure they have enough money to provide themselves accommodation, to put a meal on the table or to pay their electricity bill, they’re going to be on the streets.’’

Brazilian Gui Ferreira said he lost his job as a cleaner on March 20, six days before his work visa expired.

The 28-year-old from Sao Paolo, who has lived in the resort for two years, said his former employer had been about to support the renewal of his work visa, but the loss of the small company’s biggest contract forced him to make him and other workers redundant.

His ‘‘very upset’’employer told him it was the most difficult decision he had made in 10 years of business.

Mr Ferreira said he booked a flight home for March 24, but it was cancelled at the last moment, and a second flight was also cancelled.

He was stuck in New Zealand with no income and no way of getting home, and although fortunate to be now living with his aunt and uncle, he was slowly using up his savings.

Salvation Army Queenstown director of community ministries Lieutenant Andrew Wilson said in a statement it had seen a 600% increase in requests for help since the lockdown began, mostly for food and winter clothing and bedding.

But short-term welfare would not resolve the resort’s growing ‘‘refugee crisis’’, and it had called on the Government to allow unemployed migrants access to the unemployment benefit.

Happiness House manager Robyn Francis said the community support centre was helping laid-off migrant workers with services such as food parcels and meal and firewood deliveries.

But it was also helping New Zealand citizens and permanent residents who had lost their jobs and had applied for the unemployment benefit.

They were middle-income families, paying high rents, who had just managed to make ends meet on the wages from their tourism or hospitality jobs.

‘‘We think 12%-20% of the population here are going to be in hardship.’’