Experts say the $76 million investment would help the health system cope if the country was overwhelmed by Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions in another major outbreak.

It comes after reports in April that New Zealand had a relatively low number of ICU-beds (including a ventilator) per capita - 4.7 per 100,000 people compared to 35 per 100,000 in the United States and 29 in Germany.

The new ventilators and related ICU gear will cost $76m. The Herald understands an individual ICU-ventilator costs between $35,000 to $100,000, depending on the sophistication.

While the purchase of these machines is widely accepted by health experts, questions have been raised about whether the country has the medical workforce and ICU bed capacity available to use them all.

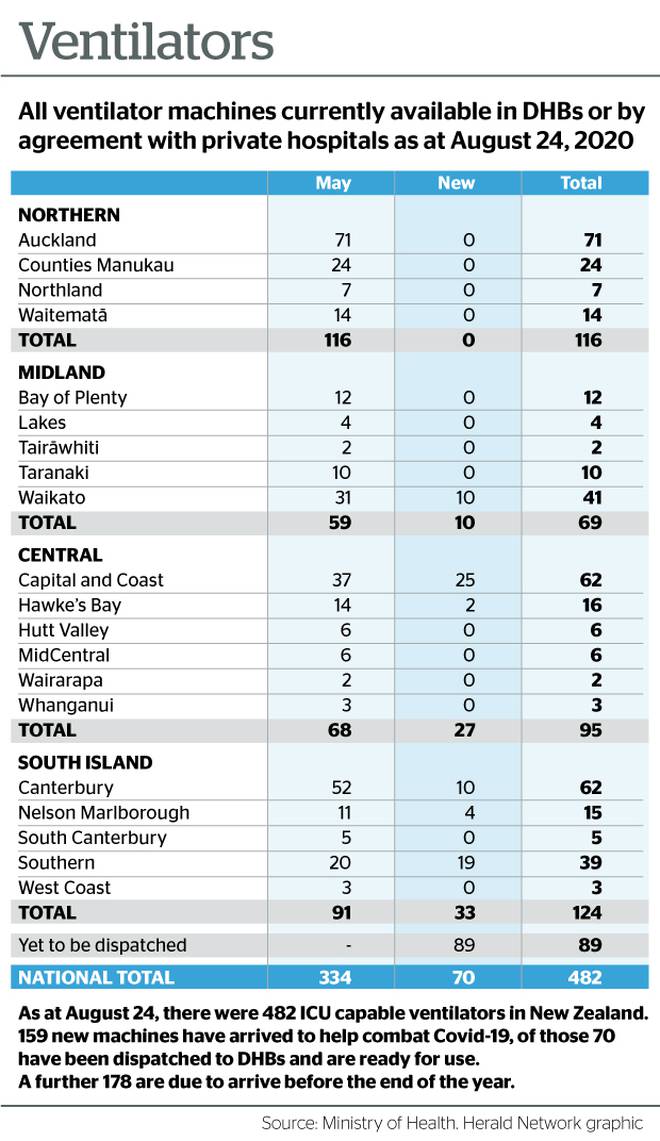

Although New Zealand has only two Covid patients currently receiving intensive care and needing a ventilator to stay alive, a Ministry of Health spokesperson said getting more ventilators was about future-proofing the country and was money well spent.

Dr Siouxsie Wiles, an infectious diseases specialist from the University of Auckland, said ventilators were in hot demand all over the world.

"The reality is that we have a current government that has a strategy and we have a pandemic that is raging overseas and there is no guarantee that a different government would stick with the same strategy."

The Herald asked Wiles whether border controls could be loosened, like some countries, including the UK, had done, now we have more ventilators.

She said: "I don't think so, because it's not just about ventilators it's about ICU beds, hospital capacity, and we know a lot more about the virus than we did back in March. We know about the serious consequences for people who have had the virus and recovered.

"I would hope [the Government] wouldn't use extra ventilators as a reason to say we should change our strategy to allow the virus to come because it still lets people get unwell.\

"Just because we have those ventilators doesn't mean those people would survive."

Lilian Su'a, New Zealand's last hospitalised Covid-19 patient, called her worried husband as she was taken to ICU.

"Pray for me. Pray for my breathing," she told him.

The 55-year-old told RNZ she was lucky to be alive after battling Covid-19 in Auckland's Middlemore Hospital for more than two months.

Su'a's condition was so serious she was sedated for more than a month in ICU during lockdown, as doctors told her family they didn't expect her to survive.

Unable to breathe on her own and after the maximum permitted time on a ventilator, doctors performed surgery to connect breathing apparatus to Su'a's trachea in a last ditch attempt to help her breathing.

After four weeks in ICU she was taken off the sedatives and began breathing on her own for the first time in weeks.

Waikato emergency physician Dr Martyn Harvey said he believed much of New Zealand's Covid-19 strategy had been driven by the lack of ventilators.

"New Zealand pretty much decided we can't afford people to get sick and require ventilators because we haven't got the capacity, so we are going to have to do an aggressive lockdown and try to stop the spread because we know if we are going to get large scale community transmission we are going to be well short of ventilators and ICU beds and everything else we might need."

He said ventilators were just a tool whereas an ICU-bed came with a whole eco-system, including additional monitoring equipment, anaesthesia technicians, doctors, nurses, infusion pumps and drugs.

However, sourcing extra ventilators was critical to help prepare our health system in case of another big community outbreak, he said.

"Getting more staff isn't like magic, you need a fair bit of time to increase capacity so it might mean we have lesser skilled docs and nurses taking care of ICU patients.

"Now it's about being prepared."

Ministry of Health director of public health Caroline McElnay said New Zealand's elimination strategy was a sustained approach: keep it out, find it and stamp it out.

"That is, to apply a range of control measures in order to stop the transmission of Covid-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand.

"As part of this strategy we have worked with DHBs to increase our ICU capacity, increase the number of ventilators and increase the national stocks of PPE gear."

Having enough equipment and preparing our DHBs to respond was part of the planning to deal with Covid-19 and a possible influx of patients, she said.

"We have seen so many other countries become quickly overwhelmed when dealing with this disease so it makes sense to both control the spread of disease while boosting our capacity to respond."

What is a ventilator?

Put simply, a ventilator is a machine that helps move breathable air in and out of the lungs. It is the machine that keeps patients with life-threatening Covid-19 symptoms alive.

What is the difference between a standard ventilator and an ICU-ventilator?

The ones currently used in ICUs are more sophisticated than standard ventilator machines, in terms of the computerisation to control the levels of air going in and out. But they are just as reliable and similar to older models.

Why are we sourcing ventilators from overseas and not manufacturing them here?

In order for the ventilators to be used in New Zealand, the machines must be internationally certified through a system called Medsafe Web Assisted Notification of Devices (WAND) and either CE (a European Union standards for medical devices) or TGA (Therapeutic Goods Administration, part of the Australian Government Department of Health responsible for regulating therapeutic goods including medical devices, prescription medicines, vaccines).

Prior to Covid-19, New Zealand had no experience manufacturing ICU-ventilators at a large scale so to start from scratch would take more time.