Research published on Monday based on data obtained by NASA's Dawn spacecraft, which flew as close as 35km from the surface in 2018, provides a new understanding of Ceres, including evidence indicating it remains geologically active with cryovolcanism - volcanoes oozing icy material.

The findings confirm the presence of a subsurface reservoir of brine - salt-enriched water - remnants of a vast subsurface ocean that has been gradually freezing.

"This elevates Ceres to 'ocean world' status, noting that this category does not require the ocean to be global," said planetary scientist and Dawn principal investigator Carol Raymond.

"In the case of Ceres, we know the liquid reservoir is regional scale but we cannot tell for sure that it is global. However, what matters most is that there is liquid on a large scale."

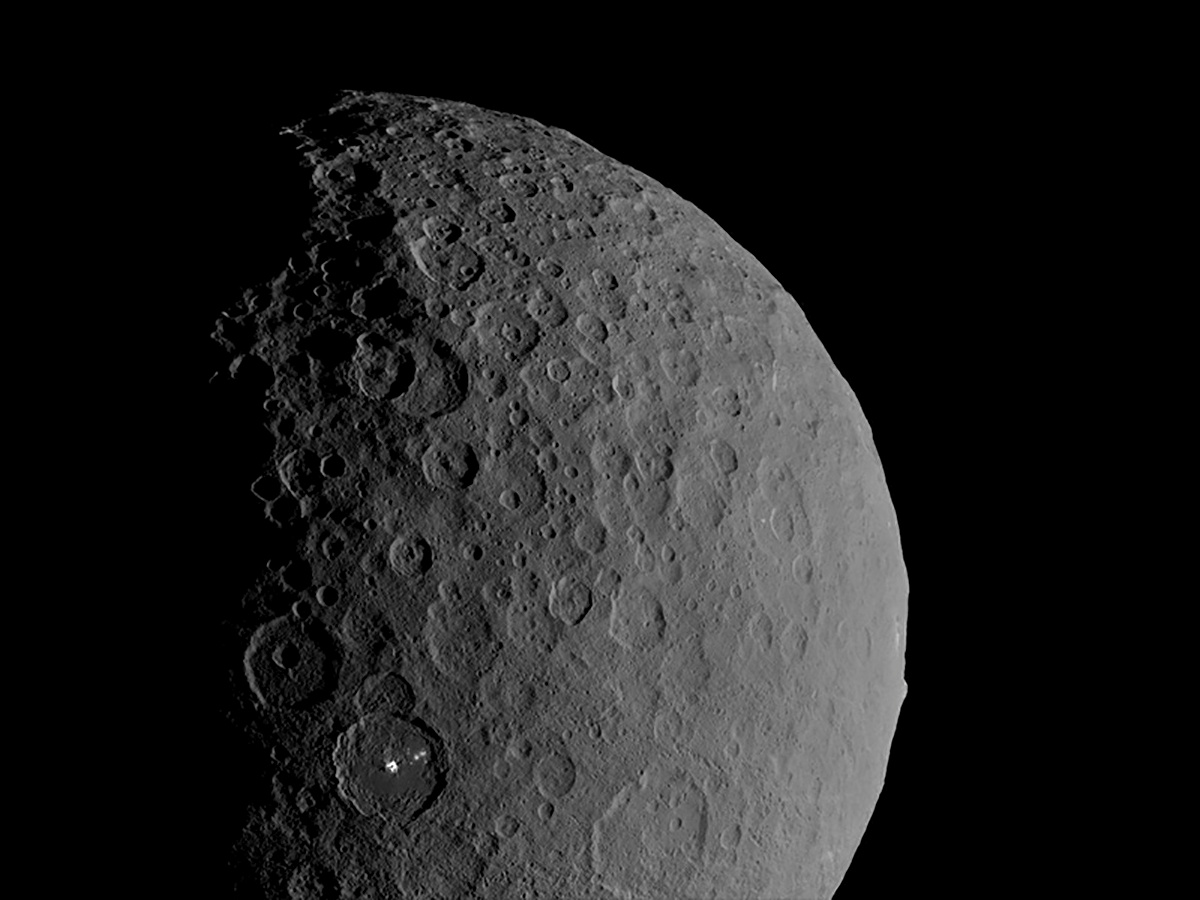

Ceres has a diameter of about 950km. The scientists focused on the (92km-wide Occator Crater, formed by an impact about 22 million years ago in Ceres' northern hemisphere. It has two bright areas - salt crusts left by liquid that percolated up to the surface and evaporated.

The liquid, they concluded, originated in a brine reservoir hundreds of kilometres wide lurking about 40km below the surface, with the impact creating fractures allowing the salty water to escape.

The research was published in the journals Nature Astronomy, Nature Geoscience and Nature Communications.

Other solar system bodies beyond Earth where subsurface oceans are known or appear to exist include Jupiter's moon Europa, Saturn's moon Enceladus, Neptune's moon Triton and the dwarf planet Pluto.

Water is considered a key ingredient for life. Scientists want to assess whether Ceres was ever habitable by microbial life.

"There is major interest at this stage," said planetary scientist Julie Castillo of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, "in quantifying the habitability potential of the deep brine reservoir, especially considering it is cold and getting quite rich in salts."