He recalls white-out conditions and men falling prey to isolation and loneliness, but in the 11 months John spent in the South Pole, he fell in love.

In the late 1970s, after returning from an eight year stint in Australia, John ran a fish and chip shop in Methven with his wife Zelda, of Ashburton.

They returned to Australia after a few years where John, a joiner by trade, carried out work on various mansions, including the now-$70 million mansion of John Fairfax.

When Zelda became homesick she returned to Ashburton to be closer to her family, and a short while later John followed.

At that time there was a call for able-bodied men willing to work on a construction team building huts in Scott Base, Antarctica.

With nothing else lined up, John thought he might as well apply, and was interviewed.

‘‘I remember coming home to Zelda afterwards and saying: ‘I haven’t got a hope in hell’,’’ he said.

Nevertheless, he found himself at a defence force base in Tekapo with a group of other recruits completing a weeklong training course designed to prepare them for life in the Antarctic.

They completed first aid and emergency response drills, including how to winch themselves out of a crevice.

When it snowed they were tasked with digging snow holes which they then had to spend the night inside.

Everything was all designed to prepare them for life in Antarctica.

‘‘And of course we had to undergo a full medical,’’ John said. ‘‘It was a long way to send you back if you got a toothache.’’

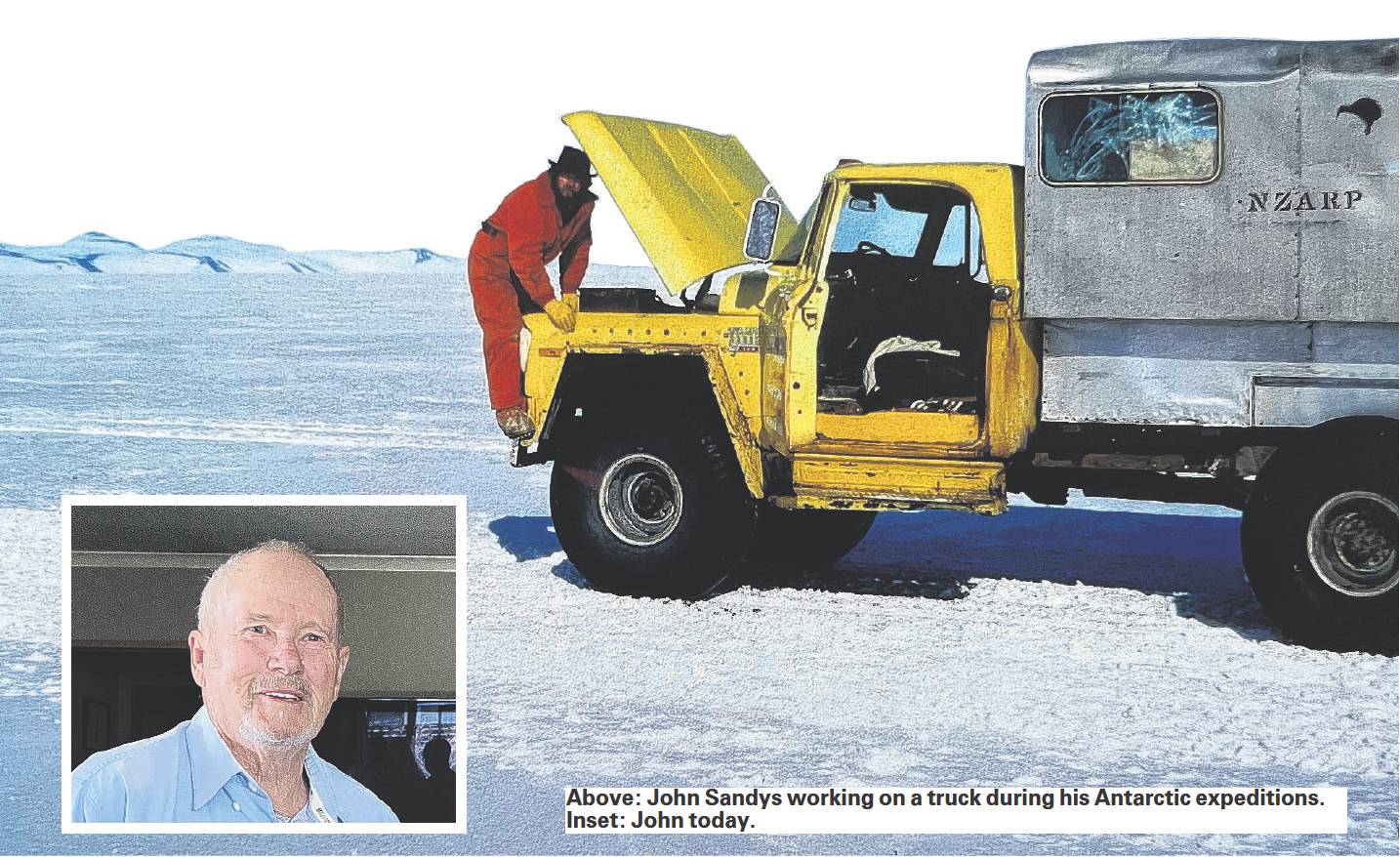

In October 1982, John, one of a dozen men picked out of 1200 applicants, flew from Christchurch to Scott Base as part of the Scott Base Construction Crew.

He would spend six months in the desolate environment, where the sanity and resilience of people were pushed to the limits. But John loved every minute of it.

He remembered getting homesick, but he found peace of mind in knowing Zelda, his wife, was ‘‘tough’, and had the support of her family to help her with their kids.

John travelled from Scott Base to Vanda Station, a research station in the Dry Valleys where he was tasked with constructing huts over a two week period.

He ended up spending 50 days there, and described the Dry Valleys as the harshest place he’d ever encountered.

‘‘It’s like a big riverbed, made up of stone and ice ... extremely dry.’’

It doesn’t rain in the Dry Valleys, but wide gullies and inhospitable climate meant no shelter against the blistering wind, which rips the moisture from everything.

‘‘It is not forgiving,’’ he said of Antarctica.

But down there John learned to appreciate the wildlife and greenery of New Zealand, instructing Zelda over the phone to water the lawns ‘‘every day’’.

He got up close with penguins and seals, watched pods of Orca from Scott Base, and learned to understand the way of life in the Antarctic environment.

He also discovered an appreciation for social connections. ‘‘There was no television or entertainment. All you had was the people around you,’’ John said. ‘‘I learned that people are fascinating.’’

Back in New Zealand the following year, despite having been rejected for a return job application, John received a call asking if he would be the overseer for the Ciros Construction Team Antarctica 1983 to 1984.

He, alongside 34 other passengers, were flown from Christchurch to Williams Field, near Scott Base.

John recalls the nerve-wracking moment the aircraft passed the point of safe return (PSR), the point in the journey at which the aircraft has used too much fuel to turn around. The pilot was forced to commit to the rest of the eight hour flight, no matter what.

Roughly 20 minutes after reaching the PSR, the pilot received communication the weather at base had significantly deteriorated. The crew had no choice but to fly into whatever conditions awaited them. John and the other passengers were seated in the cargo hold.

It was a turbulent ride, he said, ‘‘We were passed out paper bags to spew in.’’ After one person spewed it ‘‘started a chain reaction,’’ he said.

The plane landed without injury, though the pilot missed the runway by several kilometres due to white-out conditions.

The crew was forced to hunker down in the plane and wait for conditions to clear. With the plane engine running to keep the heating and radio systems alive, it wasn’t safe for anyone to leave. Not unless they wanted to risk walking into a spinning propeller, John said.

Hours later when they finally left the aircraft, they formed a human chain to keep everyone safe.

‘‘We could not see our own shoulders,’’ John said. ‘‘It was like walking through cotton wool.’’

Though John had experienced all of this the year prior, those who were arriving in Antarctica for the first time were getting an introduction into how much they would depend on their comrades for their physical and mental wellbeing.

Everyone was on equal terms, John said. Titles were stripped, even that of Prince Edward, the youngest son of the late-Queen Elizabeth II who ventured to Antarctica in 1983.

‘‘As soon as you landed on the ice, it was first name basis,’’ John said. ‘‘You had to show respect still, but it was equal respect.’’

As a result, the friendships forged in Antarctica were ones that ‘‘would never die’’, John said.

He and ‘‘the old Antarcticans’’, the men he ventured down with, try to get together once a year on the shortest day (in June) to reminisce and keep their special connection alive.

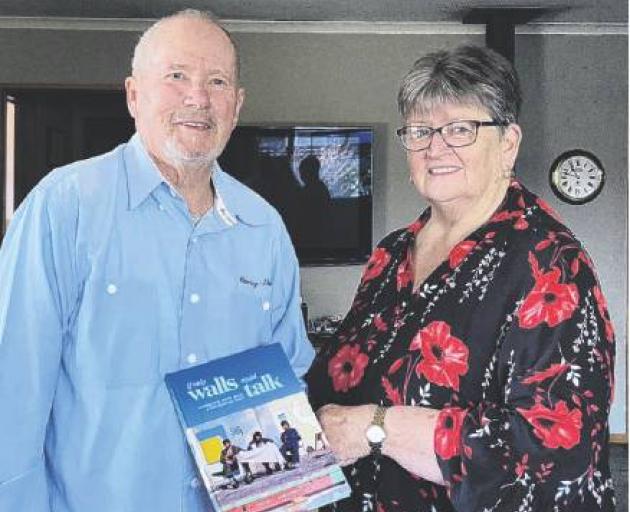

Theirs and John’s exploits have been documented in David L. Harrowfield’s new book If Only Walls Could Talk: Antarctic Huts with a Colourful Past, which tells the story of the huts built in Antarctica which are still used today.

The book was released just shy of 40 years since John’s first Antarctic experience as part of the Scott Base Construction crew, and is a welcome commemoration for all those involved.