The fault line underneath the Port Hills which overlooks Christchurch was sloping back like a lounge suite and aiming directly at the centre.

When it ruptured upwards to the northwest at 12.51pm on February 22, 2011, it stacked up energy as it went, releasing it towards the CBD, according to GNS Science researchers who have studied the worst natural disaster in modern New Zealand history over the past decade.

GNS Science seismologist Anna Kaiser says the extreme release of energy was "like a snowplough piling up snow as it moves along".

"Normally, seismic waves attenuate quickly as they move away from the fault that ruptured, but in this case there was little chance for that to happen."

Monday marks the 10th anniversary of the magnitude-6.3 tremor which caused both the CTV Building and PGC Building to collapse, claiming mass loss of life, as well as damaging thousands of other buildings, causing liquefaction, landsliding, rockfall, and cliff collapse.

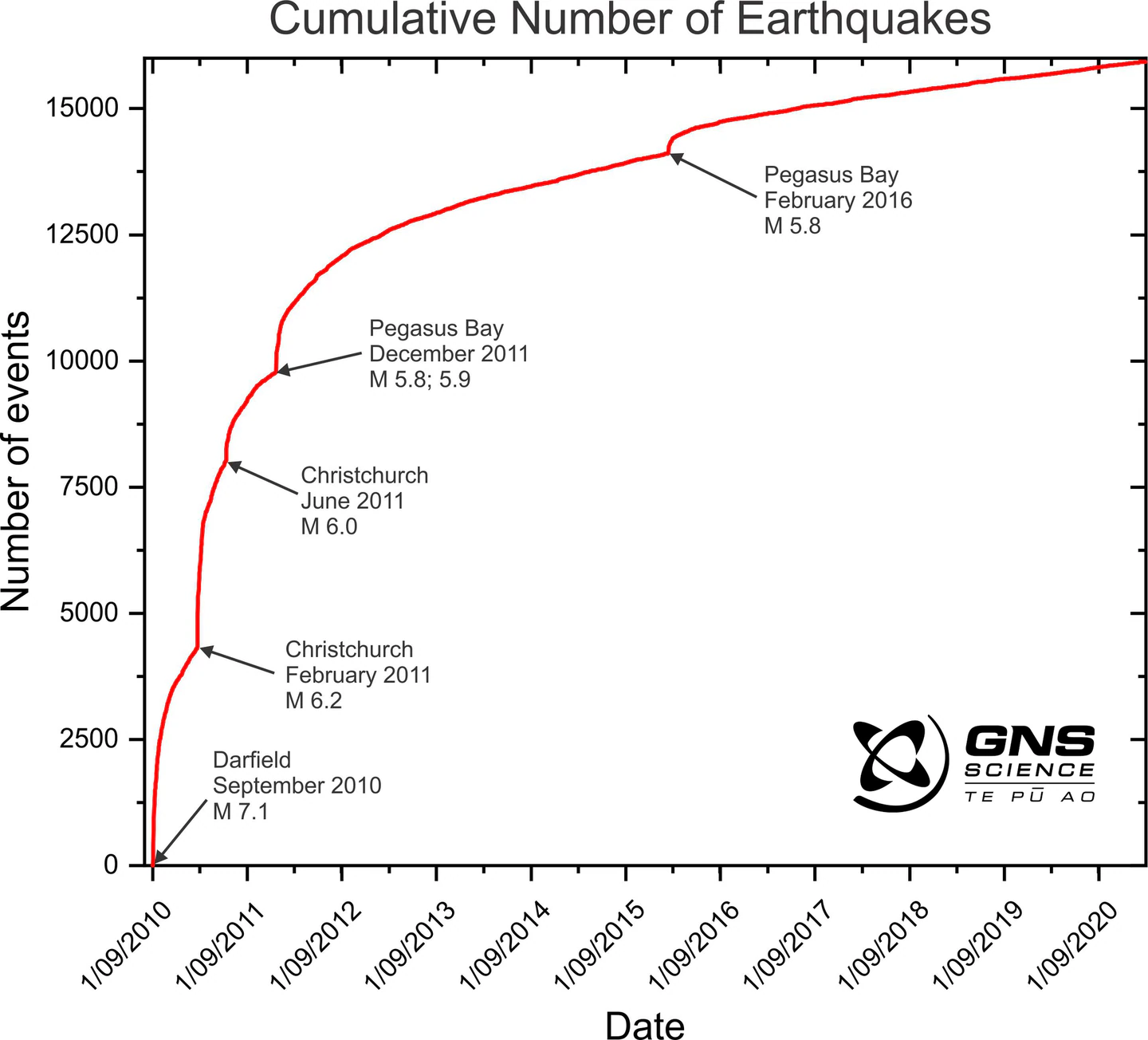

It came just months after the magnitude-7.1 Darfield earthquake in the early hours of September 4, 2010, which caused widespread damage but no loss of life.

Prior to the Darfield earthquake, only a handful of earthquakes were recorded in Canterbury each year.

But the following quakes, and thousands of aftershocks, changed views about vulnerabilities to earthquakes in low seismicity regions.

For science too, and allied fields including engineering and civil defence, GNS says the Canterbury earthquake sequence sparked many changes that have become woven into everyday life.

And for many New Zealanders, Kaiser says it reinforced the fact that Kiwis live in a country where there are many unknown active faults.

"In the future, it's almost certain there will be a damaging rupture on another unknown fault somewhere in the country."

Kaiser says several factors combined to produce extreme ground-shaking in the February 22 quake.

"Most important were the proximity to Christchurch, the amount of energy released, and the way it was directed towards the central city.

"The thick soils below Christchurch also played a role in amplifying and trapping seismic energy."

The crust under Canterbury is known to be dense and it takes a lot of energy to break a fault in strong crust because the faults there are strong.

A fault break in strong rock will release more energy than a similar-sized fault break in weaker rock.

"Think about breaking a piece of Styrofoam and a piece of particle board of the same size – the particle board will release a lot more energy," Kaiser says.

"Studies of Canterbury earthquakes have found that on average they release more energy than is typical for similar earthquakes in other parts of the world."

The communication of science was an area that saw growth and development during the quake and its chaotic aftermath.

Fellow GNS Science seismologist John Ristau says the event dramatically changed the focus of the earth science community from being mainly about the science.

"The communication between scientists, civil defence and emergency response agencies, and the public has improved over the decade since the Christchurch earthquake.

"Providing useful information to all our audiences is crucial and it's something we are conscious of with every geohazards event.

"In this way the tragic events that the people of Christchurch experienced are not forgotten and the lessons learned can be used to reduce impacts and help save lives."

Lengthy aftershock sequence

The February 22 quake is also notable for its long – and continuing - aftershock sequence, mainly due to the strong and dense crust beneath Canterbury.

There have been more than 11,000 aftershocks since the deadly jolt – and aftershocks are still occurring every few days, although many are too small to be felt.

GNS Science seismologist Matt Gerstenberger says the earthquake was extremely well-documented by a network of seismic instruments around the greater Christchurch area and the rich data collected provided many fresh insights that changed global scientific thinking about earthquakes.

The new knowledge has fed into a range of mitigation measures and other initiatives that are helping New Zealand communities become more resilient to earthquakes.

"The rupture of an unknown fault west of Christchurch that hadn't ruptured for at least 20,000 years and subsequent quakes in Cook Strait and Kaikōura have sparked major gains in the science of earthquakes and in resilience and preparedness," Gerstenberger says.

GNS Science now has a 24/7 operations centre – the National Geohazards Monitoring Centre - that monitors data around the clock and provides rapid information on earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, and landslides to support emergency responses and to inform the public.

Arrival of aftershock forecasting

Gerstenberger also notes that the Canterbury sequence was the first earthquake in New Zealand in which aftershock forecasting was used.

For the first 18 months after the quake, GNS Science provided weekly updates on the probabilities of aftershocks occurring in a given time period.

The figures are currently updated annually. Aftershock forecasts have been calculated for several major earthquakes since Christchurch.

"They are useful for a range of end-users including engineers, infrastructure managers, the civil defence sector, the insurance industry, and government planning," Gerstenberger says.

"The probabilities are fed into new building standards, so that our buildings will be more resilient to earthquakes in the future. They are also used by the insurance industry to compare risks from different hazards.

"For all sections of the community, it is useful to have a general indication of what we can expect to help with planning and preparedness."