A major plank of German naval strategy leading up to the war was to concentrate their dreadnoughts into one fleet.

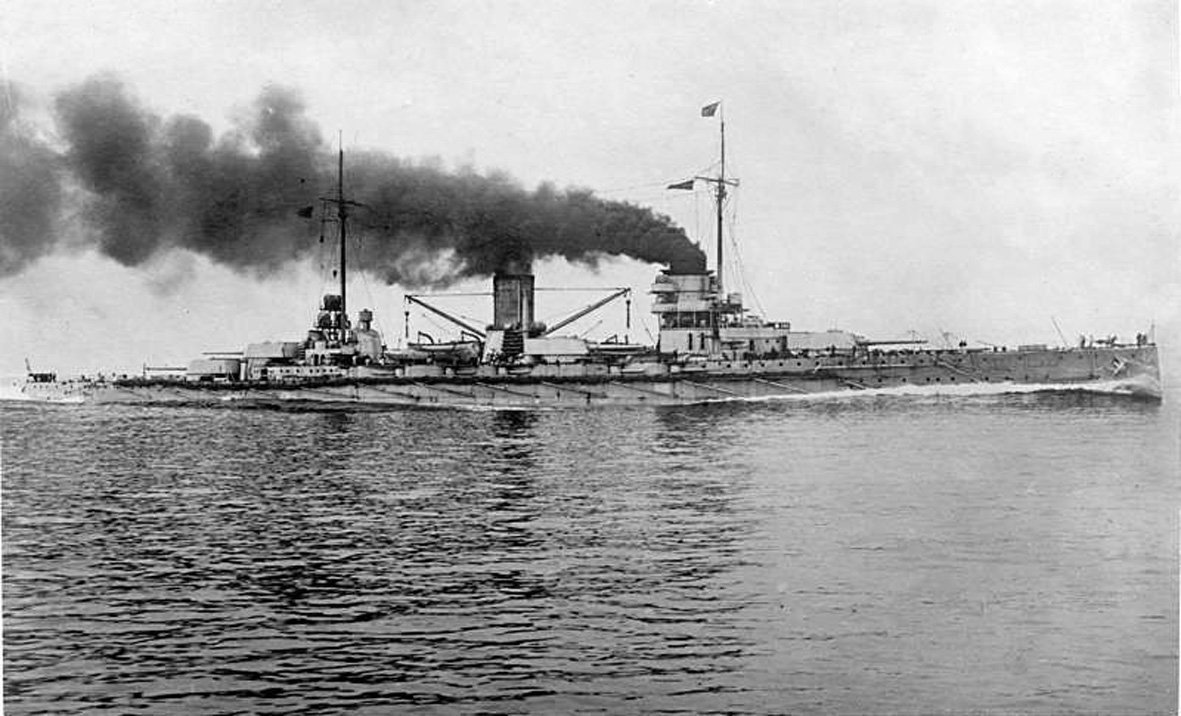

It was thus a matter of some considerable irritation to the German naval high command when the Kaiser decided to detach SMS Goeben, one of the most modern, fast and powerful capital units in the German navy for service in the Adriatic in 1912. The German naval high command became alarmed as war became imminent, as Goeben risked being caught without access to a friendly port, and thus could not hope to survive.

The Kaiser’s belief Goeben could return home to Germany after war was declared was plainly absurd. However, increasingly desperate pleas by the German high command would not sway him — Goeben stayed where she was.

When war came on July 28, 1914, Admiral Souchon extricated Goeben from the Adriatic and awaited events and instructions off the coast of North Africa. The Kaiser ordered the ships to return to Germany, but the chief of the Kaiserliche Marine, Alfred von Tirpitz instead issued an order to proceed to neutral Constantinople.

By a series of adroit manoeuvres Souchon obeyed Tirpitz and avoided the superior British forces sent to destroy him. Goeben reached the safety of the Turkish guns covering the Dardanelles on August 10, with the funnel smoke of the pursuing British squadron visible on the horizon behind them.

The German crews were now safe, but their ships were not. Turkey was a neutral power, and the ships faced internment after 24 hours unless they sortied to certain destruction at the hands of the British squadron outside.

Furious activity by Souchon and the other German military officers in Constantinople produced a remarkable solution well within that timeframe. Less than a week had passed since the humiliating seizure of the two Turkish dreadnoughts by the British.

On August 11 the Ottoman Government announced unilaterally that they had recovered their loss by purchasing the German ship. Goeben became Yavuz Sultan Selim. The Turkish payment to the German Empire not only secured Goeben; it secured the services of the German crew too. On September 23 Admiral Souchon officially became commander in chief of the Ottoman Navy. His officers and men remained at their posts and merely exchanged their German naval caps for Turkish red fezzes.

Ashore in Constantinople the highly capable German diplomatic and military cadre worked hard to precipitate incidents that would commit the Ottoman Empire to war. On October 27 the Turks ordered Admiral Souchon to sortie into the Black Sea.

A week later, on November 12, the Sultan finally bowed to the inevitable, and declared war on the Allied powers.

The Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war at this moment was a far more serious matter for Britain than it would have been three months earlier. The shattering defeats inflicted upon the Russian Empire by the Germans in August 1914 meant that the Russians were not able to put pressure on the Ottoman Empire from the north in the expected manner. Ottoman forces could thus be moved south to threaten British positions in Persia and around the critical Suez Canal. Few British troops could be spared to counter these forces.

But above all there was the freshly arrived Goeben/Yavuz. She was superior to any individual Allied unit then in the Mediterranean, and from her secure base in Constantinople she posed an immediate danger to the convoys ferrying men and materials through the Suez Canal.

French and British efforts to force the Dardanelles, capture Constantinople and eliminate Yavuz were therefore unrelenting from the moment war between the three powers was declared.

However, purely naval efforts to silence the Dardanelles shore forts using battleships proved both futile and highly expensive in terms of both men and ships. These setbacks led to the project to land a major land force on Gallipoli Peninsula in order to silence the Turkish guns that defended the approaches to Constantinople and Yavuz. The use of land forces was strongly supported by Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. Just over a month later, the Anzacs came ashore and the shooting began.

Churchill, the prime architect of the Gallipoli operation, subsequently wrote Yavuz was responsible for "more slaughter, more misery and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship". Churchill would only have written this if Yavuz had been a significant motivation behind his successful push for the Gallipoli campaign.

He was right in terms of her impact upon world affairs. Yavuz would enjoy her distinction even if she had done nothing more than bring the Ottoman Empire into the war, but she remained the most formidable unit in the Black Sea throughout both world wars. Yavuz finally went to the breakers in 1973. Only her central propeller now survives in front of the Istanbul Maritime Museum.

As this object did far more than anything else to propel the Anzacs to Gallipoli and to create a new sense of national awareness in Turkey, Australia and New Zealand, it is worth paying it a visit if you are on the way through Istanbul to Anzac Cove.

- Dr Robert Hamlin is a senior lecturer in the marketing department at the University of Otago.