How's the battle?

One of the first conundrums one must consider when faced with a cancer diagnosis is whether to buy into the idea one is involved in some sort of battle.

The term is very common.

I thought one possibility might be to wait until the consultant came on her daily round with her doctors, show her the edge of a blade I could have hidden under my sheets and whisper conspiratorially ``I'm carrying''.

I'm not sure how that would go.

Not only that, but somehow it just didn't seem to fit in with the general vibe of my treatment, which involved a gentler regime of chemotherapy drips and people being nice to me and nurses who looked after my every need and provided a level of human warmth and compassion that never seemed to wane, no matter the time of night or day.

Then there were doctors who used their skills and training and the results of tests and scans to develop a treatment programme for me, with nary a sharp bladed sword or a blood-stained spear anywhere to be seen.

Of course, people who battle cancer may lack the natural subtlety others exhibit, perhaps forming bands of fighting men based on a Middle Ages model, men on horseback with battle-axes and swinging maces who would have absolutely no compunction about attacking Dunedin Hospital, putting it under siege or taking hostages until cancer was delivered to them for summary execution.

I don't know, but I made an early decision not to battle cancer, but merely to have it, with the hope that in the future I wouldn't have it.

That's how I'm playing this.

Sweating the small stuff

I was in the middle of some medical procedure or other, perhaps a bone marrow biopsy or a lumbar puncture, when I suddenly wondered if I would be one of those people who gets through cancer and says they are no longer going to sweat the small stuff any more.

This is very common.

The general narrative is a person is cured of cancer, then realises they have been worrying about small insignificant things that now, with a new lease of life, they decide to shed like an old skin to begin a new existence in which only the important things matter.

Maybe.

As I lay there, I couldn't help thinking about old Rowdy Campbell from school.

He'd stop sweating the small stuff just like that, just as he managed to beat me with such ease in exams, and made the First XV without even trying, then went on to earn more than me at a better job and live in a bigger house.

The thought infuriated me.

I wondered if I'd been successful enough, and how I should measure that.

I could only think of people who had done better than me, and how unfair that was because they did so using a mixture of dumb luck and big talk, not by carefully compiling a set of skills as I had done.

And yet now they drove new cars down George St and had well-buffed fingernails and expensive watches.

I thought about my bank account and worried about how much was in there, not because there wasn't plenty to get by on, but because I had a target and I hadn't quite met it.

If I was better at saving money perhaps I could buy more of the sort of things that make you happy, like possessions of various types, perhaps a new car or a trip to the nail salon.

Maybe if I get better I should start a new diet and exercise regime.

Then I thought, maybe if I get better I could stop sweating the small stuff.

But I realised I didn't even know what the big stuff was, and whether it would entertain me so richly as the small stuff if I was to concentrate all my thoughts on whatever it might be.

So I decided I wouldn't.

Good things about cancer

There are things I like about my cancer.

I like that it has no malice, no spite, it means me no ill will, it just is, it is what it is, it is doing what cancer does, just as I do what a human does, just as dogs pee on lampposts.

I cannot ask it to do otherwise.

I like that the cancer, this malignant multiplication of lymphocytes, is not just free of malice, it is also free, if you think about it, of any meaning at all.

There is no why or wherefore; cancer is just doing what cancer does, and it happened to go cancery on me just because, for no reason other than it did.

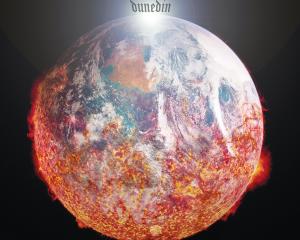

That's somehow elegant, and fitting in a universe with no apparent meaning on an Earth hurtling from blackness to nobody knows where.

I admire its honesty.

And perhaps the cancer was always going to form, and it was always going to form in me, like millions of cancers have and will form in others, because that's what cancers do.

And who can complain, or ask that things be different?

*Mr Loughrey is being treated for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma by doctors and staff of ward 8C at Dunedin Hospital, a group of people who are not just beyond excellent but provide a sterling service. He has also been helped in his recovery by some great district nurses.