Take finance and expenditure for example, which is generally regarded by MPs as the one they want to serve on given that it’s the one which deals with the taxpayer’s money.

Or the privileges committee, which journalists are seemingly obliged to call "the powerful privileges committee" as it deals with issues of discipline around the Parliamentary complex.

But at the other end of the spectrum sits the regulations review committee, a body deemed so important that National has foisted Sam Uffindell off on it.

Regulations review is a committee which MPs like to joke about ... it has the reputation of being a little nerdy, dealing as it does with some of the more esoteric sections of the country’s laws.

But how laws and their ensuing regulations are drafted are vitally important: if an issue goes to court, the first thing all parties will do is look at what the legislation actually says, and ambiguity leads to a judge becoming the arbiter of whatever it was that Parliament was trying to achieve.

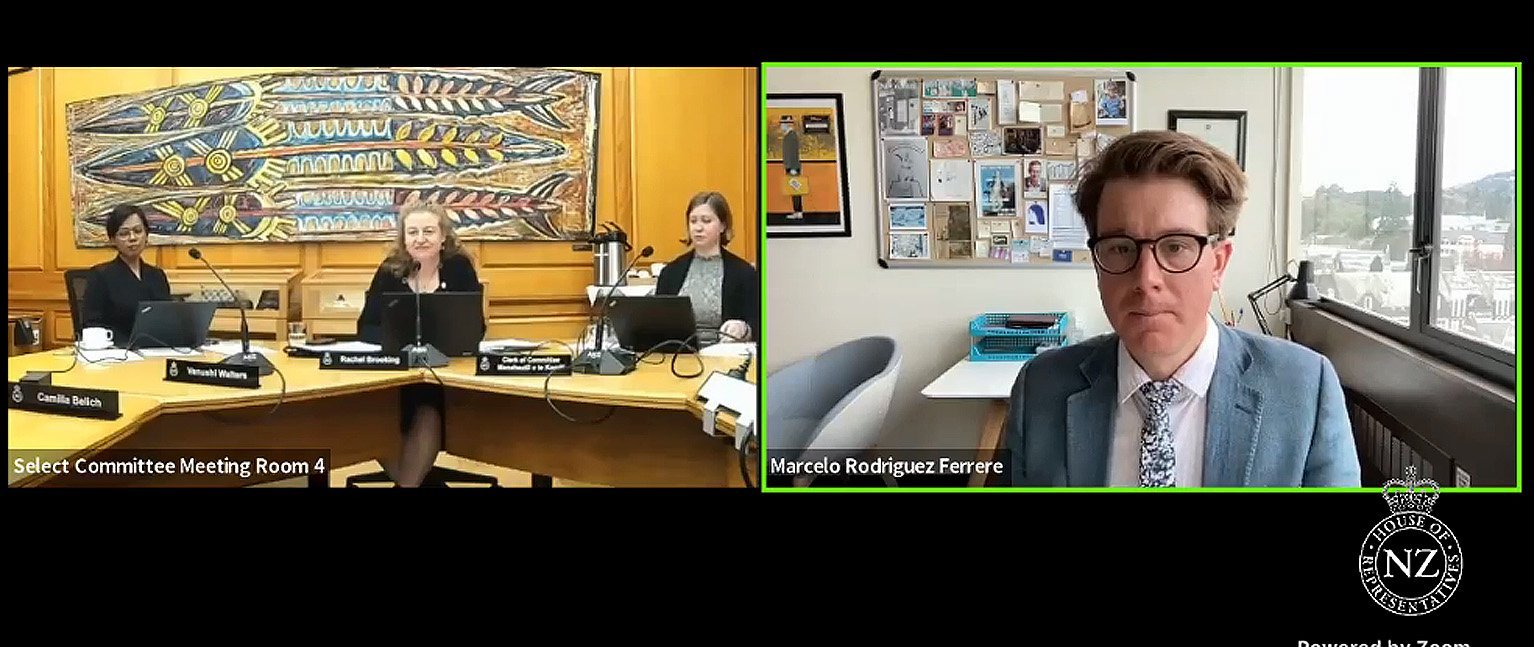

The committee’s ambit can also be quite sweeping and its hearing this week, presided over by its deputy chairwoman Dunedin Labour list MP Rachel Brooking, was of vital interest to New Zealand’s 6.35million dairy cattle, 27million sheep and millions upon millions of chickens ... let alone the people who farm them.

As Southern Say noted a few weeks ago, Parliament is already debating an Animal Welfare Bill, but that proposed law change is mostly about stopping live animal exports.

While that issue is of vital concern to the New Zealand Animal Law Association, which was the committee’s invited guest this week, its presentation encompassed the welfare and wellbeing of the entirety of this country’s farmed livestock.

Beaming in live from the Richardson building, University of Otago law lecturer and NZALA member Marcelo Rodriguez Ferrere said the current regulations designed to ensure that farmed animals were happy and healthy were "a classic indication of regulatory failure and delegated legislation not working the way that it should".

It is here that things do indeed get a little nerdy, but bear with.

Parliament creates both primary legislation - the main Act which sets out the law - and secondary legislation, where the regulations enabled by that law are set out.

In this particular instance, Parliament has passed the primary legislation, the Animal Welfare Act - which Mr Rodriguez Ferrere described as world-leading in its approach to animal welfare issues.

Section 10 requires that farmers meet the "physical health and behavioural needs" of their animals so that - critically - they have the opportunity to "display normal patterns of behaviour".

It is those five words which have been the basis of much of the legal action that the NZALA has taken in this field to protect animals, most notably its challenge to the use of farrowing crates by pig farmers.

Subsequent to that Act being passed, regulations and codes of welfare, the secondary legislation, were drafted, to set out specifically for the various species farmed for various purposes, what responsibilities those in charge of their husbandry had to meet.

Codes of welfare cannot be enforced in and of themselves, but compliance with them can be a defence if charged under the Animal Welfare Act.

This is a case where one size does not fit all - what a dairy cow needs is not necessarily what beef cattle need, and that will not be what a pig or a sheep needs.

The point which NZALA wished to make to the committee, and it had already written a report which cogently pointed this out, is that a vast gulf exists between what the Act says and the effectiveness of the welfare codes.

The standards as written lacked clarity and undermined the aim of ensuring animal welfare, Mr Rodriguez Ferrere said, and in some cases were more than just inadequate - there is no code at all for farmed fish.

"That undermines not only the safety of those animals but also ultimately New Zealand’s reputation as a leader in agriculture and animal welfare and high standards."

Before you dismiss these as the concerns of a bunch of hippies and vegans, it is well worth noting that both Dairy New Zealand and Federated Farmers, broadly, agree with the NZALA that animal welfare is of paramount importance, even if their viewpoint partly comes from a commercial perspective rather than from a preference that animals not be eaten at all.

Animal welfare scandals are not widespread, but when they emerge they have the potential to taint the image of New Zealand farmers as being responsible and caring stewards of their herds and flocks.

What the NZALA would like to happen - and quite likely the beasties which they advocate for as well - is for all codes of welfare to meet the standards set out by the Act, something which it claims is not the case now.

Further, it would like the National Animal Welfare Advisory Committee, which advises the Minister of Primary Industries on these matters, to be demonstrably independent and have some actual teeth - ultimately, the association would like a Parliamentary Commissioner for Animals to be established, with a role similar to existing commissioners for children and for the environment.

Coincidentally, while all this was going on Southland National MP Joseph Mooney was in the debating chamber talking about winter grazing.

This is a big issue for Southland farmers, who feel that ignorant townies do not understand what they are looking at when they tut-tut over a photo of cattle standing in a muddy field.

"Just one example in my electorate is a farmer who grows 27ha of fodder beet to feed 570 cows for 72 days during winter," Mr Mooney said.

"That’s a period when grass doesn’t grow in Southland because the ground is too cold and there is limited sunlight.

"Fodder beet grows 15 times the feed that grass does, and if that farmer tried to feed their cows on grass during that same period, they would need 410ha of grass instead of 27ha of fodder beet.

"That 410ha would turn to mud, and the grass would take two years to grow back naturally."

Mr Mooney and his party’s agriculture spokeswoman Barbara Kuriger have called for the Government to scrap plans which would require farmers to apply for resource consent for winter grazing, something which they estimate could cost farmers collectively multi-millions of dollars.

Labour have resisted this claim with associate minister Meka Whaitiri (on behalf of the Minster for the Environment) stressing to Act New Zealand agriculture spokesman Mark Cameron during Thursday’s Question Time that the consent requirement only applied to a slope of greater than 10 degrees, that just 6.5% of Southland winter forage land was that steep, and that for many of those farmers winter grazing was already a permitted activity.

The winter grazing issue is set to rumble on for a good while yet, but serves as another reminder that regulations matter - as does the committee which reviews them.