Ahead of Dave Cull clearing his desk after nine years as mayor of Dunedin he spoke to Chris Morris about a tumultuous time in the city’s history.

This interview with Mr Cull was first published in 2019 and we are republishing it following Mr Cull's death today.

Getting ready to say goodbye after nine years occupying Dunedin's mayoral office is "a funny feeling", Dave Cull says.

The phone is not ringing as much and a once-congested diary is starting to thin out, as councillors who once sought daily meetings hit the campaign trail instead.

The council is not making any big decisions ahead of next month's election, and ratepayers who might have wanted something from him now see little point in asking.

All of which leaves more time for contemplation, as Mr Cull sifts through old papers and throws some into the wheelie bin now positioned beside the mayoral desk.

He won't miss the paperwork and he won't miss the early morning starts, which usually began with emails at 5am.

And he insists he has no desire for one last grand gesture, to leave a legacy of sorts.

Instead, he lists achievements in managerial terms - improvements in council governance, a broad consensus around the council table and a more strategic approach to the issues facing the city.

A council, overall, that has been forced to evolve and a city now going from strength to strength.

He does not want to claim all the credit, except to say he had been "part of a very positive process".

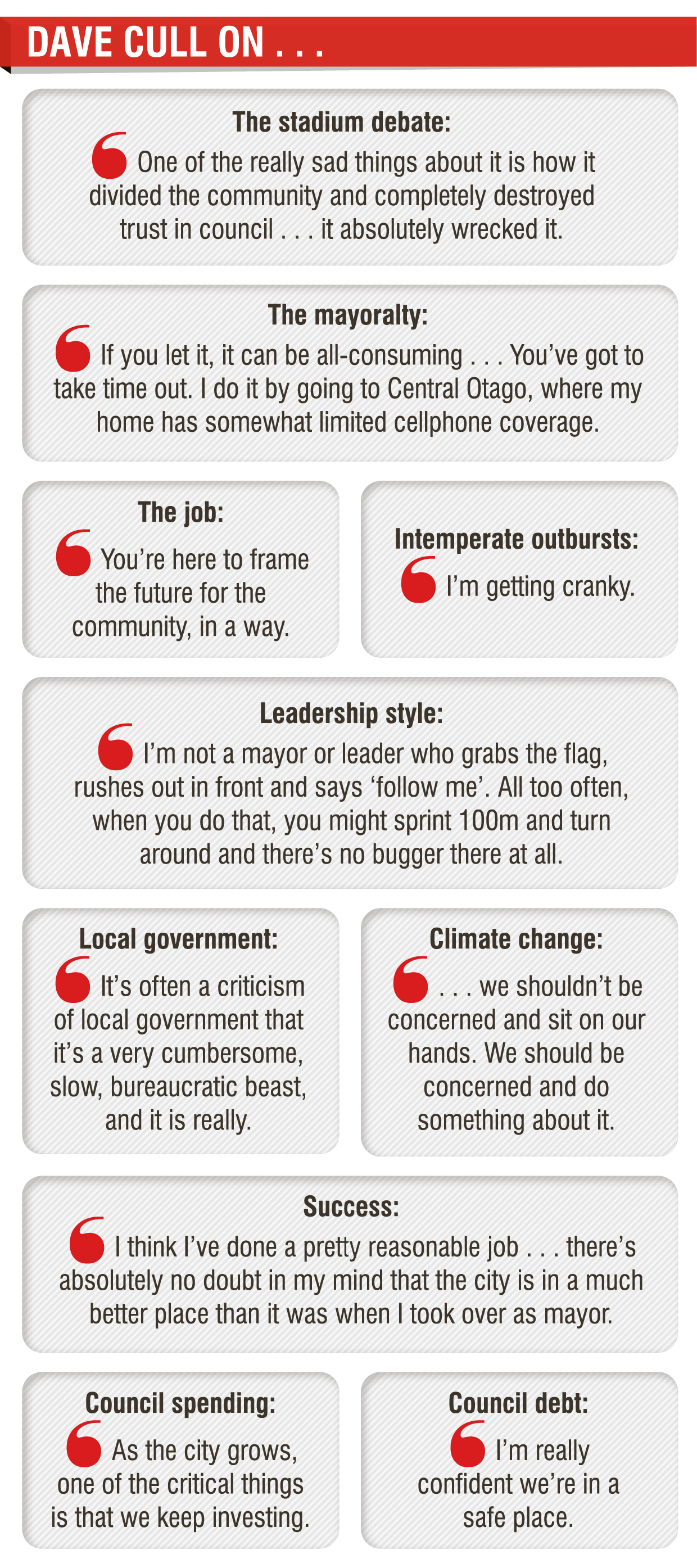

"I think I've done a pretty reasonable job. I guess if you judge it by outcomes ... there's absolutely no doubt in my mind that the city is in a much better place than it was when I took over as mayor."

It was a job Mr Cull came to almost by accident.

The boy from Southland, who moved to Dunedin to study in the 1960s and never really left, came to local politics after a career as a television presenter, hosting lifestyle and home improvement shows, and author.

By 2007, when he had been replaced on screen "by younger models", his opinions about Dunedin politics saw him challenged by friends to "put his money where his mouth was".

Mr Cull found himself invited to a meeting by "a group of people in the community ... who shall remain nameless", but who wanted to encourage new candidates to seek council seats.

Mr Cull agreed to be one and was joined by other now-familiar faces - Chris Staynes and Kate Wilson - among a group of five candidates.

"We called ourselves Greater Dunedin," he said.

"I think we felt, and some of the people that supported us felt, that there was just a sleepiness about the council - just a lack of energy - and it needed new blood.

"But we didn't agree, or even try to come up with, particular policy planks. We just had some principles."

One of those was fiscal responsibility, and it was soon to be put to the test.

By 2008, Cr Cull was among speakers addressing a packed town hall meeting as debate raged over the merits of a new roofed stadium for the city.

On March 17, despite significant opposition including from Cr Cull, who argued the financial risks were too great, the council voted 10-4 to build the stadium.

It was an issue Cr Cull returned to in 2010, when he challenged two-term mayor Peter Chin for the top job.

At the time, the Greater Dunedin group had decided to expand - bringing in new candidates including Richard Thomson and Jinty MacTavish - and wanted to put forward a mayoral candidate.

"I looked around and there was only one arm up, and it was mine," Mr Cull said.

In the end, the election was not even close - Mr Cull unseated Mr Chin by about 22,000 votes to 14,000, and later put his victory down to the community's demand for change.

But, soon after taking office, the council was rocked by a bombshell when the financial plan underpinning the decision to build the stadium began to unravel.

Dunedin City Holdings Ltd - the parent body for the council's group of companies - had been pressured by the council to gather $23.2 million a year in dividends and other payments from its subsidiaries and transfer it to the council, which used it to offset rates.

That money was expected to continue, and help pay for the stadium, but in early 2011 it was confirmed the companies could no longer afford to pay $8 million of the dividends expected each year.

Mr Cull said when he first heard of the shortfall, the DCHL board could not immediately be gathered in once place, so he had several meetings with smaller groups of directors.

"I would say to them 'well - what can DCHL afford?'

"I kept getting different answers and that was completely unsatisfactory. The board didn't actually know what they could do."

The payments continued to fall and the political firestorm which followed eventually led to a major shakeup.

A review by Warren Larsen identified a "high level of dysfunction" within DCHL and the potential for financial problems to become "very serious", and recommended wholesale changes.

Directors were removed, including city councillor Paul Hudson from his dual role as DCHL chairman, and governance structures changed.

During budget deliberations in 2012, when a further $4million budget hole was revealed, the council was forced to slash capital spending across the board.

The austerity which followed avoided a rates hike otherwise predicted to hit 11.9%, followed by 8% the next year, which Mr Cull said would have been completely unacceptable.

"I just remember thinking, and saying out loud, 'there's no way we're going to do that ... it'll be 5% next year, 4% the one after and 3% thereafter'.

"It took a lot of squeezing, but we got there."

But the belt-tightening was not without consequences.

As well as squeezing council budgets and staff, there was an opportunity cost for the city.

"The upshot of that would be, where else would that money have gone? It would have gone into investment in renewals or maintenance or whatever - and it didn't."

And even now, years later, Mr Cull remained deeply sceptical about the financial promises underpinning the stadium debate, and those who made them.

"I think it was not transparent ... they were either really foolhardy or not up to the job.

"At worst, they were a calculation that by the time it was discovered that they couldn't sustain them, we'd have to find some other way of replacing it [the funds]. We'd have the stadium up."

The fallout also divided the community and "absolutely wrecked" public trust in the council - a legacy which continued to be felt today, Mr Cull believed.

"That has been, in some ways, far more harmful than the financial costs.

"I think that bitter cohort in the community, the seeds of their attitude were sown during that time, so we're still paying quite a high price."

BUT it was far from the only bump in the road for Mr Cull, although he was elected again as mayor in 2013 and 2016.

Along the way his council also faced the shock and upheaval of the $1.5 million Citifleet fraud, when in 2014 a council manager was found to have sold 152 council vehicles, and pocketed much of the proceeds, over a decade.

The manager at the centre of the fraud took his own life when confronted, but another major shake-up within the council followed, as staff who failed to identify the fraud resigned and internal controls were tightened.

Then, in 2015, a torrential downpour exposed glaring deficiencies in core council infrastructure in South Dunedin as the council's response on the night stuttered.

An investigation eventually pointed the finger at problems at a pumping station, which made the flooding worse, while deficiencies in mud-tank maintenance were also identified.

The failures led to more change and "severe ramifications" for staff, who resigned, and Fulton Hogan, which lost its contract.

Then came the revelations the council-owned lines company, Aurora, needed a massive cash injection to fix or replace power poles and other neglected parts of its network - said to be another symptom of the companies' past focus on dividends to the council.

That led to yet another shake-up, as a Deloitte review recommended changes. Aurora and Delta - previously interrelated companies, both owned by the DCC - were separated, and the chief executive of them both, Grady Cameron, stood down.

Together, they were the kind of challenges and pressures that could squeeze someone until they snapped - and Mr Cull did, more than once.

Most notably, that happened as Mr Cull fought a running battle with his most outspoken councillor, Lee Vandervis, during heated exchanges in the council chambers.

In one spectacular bust-up in 2015, Mr Cull labelled Cr Vandervis "a liar" and ordered him out of the chamber, amid claims of a backhander paid by the councillor to secure a council contract in the 1980s.

Cr Vandervis later accepted a $50,000 payment to settle a defamation case he brought against Mr Cull, who refused to apologise and insisted his defence was "likely to prevail if the case had gone to trial".

But apologies were to become a recurring theme for Mr Cull, who had to say sorry after describing the Dalai Lama as "the leader of a minority sect" in 2013, and again last year after interrupting a ratepayer's tirade to ask if he was "deaf or just stupid".

Mr Cull, asked about the outbursts, accepted he had overstepped the line "from time to time".

"I'm getting cranky.

"I get goaded into intemperate responses that I regret ... I think I have learned a bit from that."

He coped with the pressures in part by finding time to escape for a weekend away, once a month, with wife Joan Wilson.

"If you let it, it [the mayoralty] can be all-consuming and it can be the priority. You've got to manage it.

"I do it by going to Central Otago, where my home has somewhat limited cellphone coverage."

But, despite the challenges, Mr Cull remained upbeat about the council's performance.

The difficult issues that emerged had to be dealt with, but had not distracted from the council's focus on the future and what it wanted the city to be like, he said.

Realising that vision began with better governance, strategies and community consultation, but also included initiatives - like cycleways - designed to make the city more liveable, he said.

"I don't think those other things - however lamentable they are - have stopped us from doing that job, and I think pretty well. The outcomes are there for everyone to see."

MR Cull reeled off a list of other achievements he was also pleased with, from a more "outward-looking" city with better relationships abroad, to the city's status as a Unesco City of Literature.

The council was also in a good position financially, regardless of critics who pointed to rising rates and mounting debt, he said.

Core council debt - including stadium debt - was lower now than when he became mayor. Debt servicing costs were a smaller proportion of council spending than in 2010 and council rates remained the lowest of any metropolitan centre in the country, he said.

"That doesn't mean that I think you can just keep piling on rates increases, because that's an affordability thing - I get that.

"But ... we're actually in a pretty good position."

He admitted to being frustrated by the way debt was "misrepresented" by some councillors and sections of the public, and troubled by suggestions spending should be slashed.

It was "critical" the council keep spending, including on infrastructure to cater for future growth, or the city would "grind to a halt".

"If we don't have the money to spend, and we don't invest in growth infrastructure, then you end up with not enough housing, so people can't come here, so the population declines again and it's a spiral to the bottom."

Investment meant more debt, to spread the cost and avoid higher rates rises, but the council had assets - like the $90million Waipori Fund or the $90 million property portfolio - it could cash in, if needed, he said.

"I'm really confident we're in a safe place."

There were still big challenges ahead, including housing, but perhaps the biggest was the storm clouds of climate change gathering on the horizon.

Mr Cull supported the overwhelming scientific consensus and said the city - like the world - should be "very concerned".

The impact would be different in different areas, but talk of sand groynes to solve the problems facing South Dunedin was overly simplistic, he said.

It was the groundwater table already close to the surface in South Dunedin, and the threat of it being lifted higher still by sea-level rise, that was the real issue there, he said.

The DCC was already working with GNS Science and the Otago Regional Council to find out exactly what was happening beneath residents' feet, but one thing was clear, he said.

"There won't be one solution. There will be a combination. It might be Jules Radich's [groynes] over there; it might be Lee Vandervis' big pumps here ... but there won't be one."

There were also two "extreme fallacies" in the debate over the future of South Dunedin.

"One is that all of South Dunedin will need to be retreated from. And the other fallacy is that none of South Dunedin will need to be retreated from.

"It will be somewhere in between."

Both the council and residents had a big stake in the debate, given the infrastructure and private property under threat, but the wider community had also made its feelings clear about the need to act, he said.

"We could spend the next 30 or 40 years arguing about it, by which time it's probably going to be too late, so I think we should be concerned.

"But we shouldn't be concerned and sit on our hands. We should be concerned and do something about it."

But, after his nine years in charge, that would be a challenge for the next council and the next mayor.

In the meantime, Mr Cull has a few weeks left to finish clearing his desk and say a few goodbyes.

It was the people he had worked with he would miss the most, he said.

"I love them dearly and I have a great time with them."

Comments

Dunedin will miss your hard work and dedication as Mayor Dave, and I think even your detractors would grudgingly respect this. Thank you for all your work and deepest condolences to your family. RIP. Ken and Moira Taylor.