So far, it seems we have been given only partial answers to what is a "wicked" problem, that is a problem with many interdependent elements such that changing one part will change others in chain reactions that are largely impossible to unravel. The 2006 Report by economist Nicholas Stern is one of the earliest contributions, and Lord Stern remains one of the most influential advisers on climate change policy at the global level.

But lifestyles that have evolved over a century or more, and that are dependent on corporations and supply chains that span the globe, have not responded to the economist’s price signals at anything like the rate required for the rapid transition that is needed. Why not?

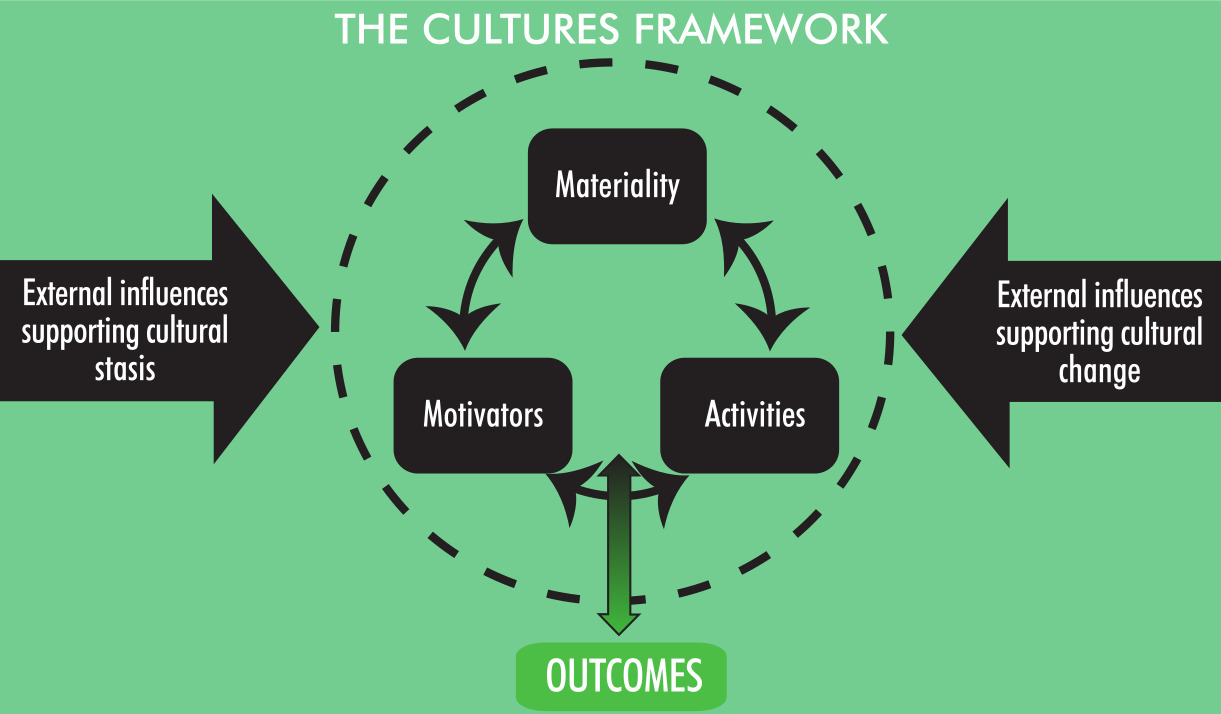

Prof Janet Stephenson’s new book, Culture and Sustainability, offers far more complete answers. At its heart is a simple but powerful set of ideas, the "Cultures Framework", that asks us to position the lifestyles we lead now ("activities" in the framework) in the context of the motivators that drive activity (norms, beliefs, values, knowledge, symbolism), and the enormous range of physical assets ("materials") that enable us to lead our lives in the way that we do. These come together in complex interdependent webs from which it can be very hard to escape.

So, the next question posed by the framework is to ask how much "agency" we have to create change: how restrictive is the "agency boundary" that encircles activities, motivators and materials? Finally, the framework asks us to identify "external influences" on these webs: those that limit, and others that support change towards desired "outcomes".

The framework was initially developed a decade ago by a team of researchers, led by Stephenson, from sociology, economics, physics, psychology, engineering, law, marketing, management, system dynamics and human geography. Since then it has been used in more than 100 research projects in more than 30 countries around the world. If we need a framework that can bring together a broad range of social sciences on a global scale, this is it. It is the most powerful diagnostic we now have to respond to the crises of climate and sustainability.

But this deeper understanding of the complex inter-dependencies within a "cultural ensemble" can also help us to loosen some of these constraints and set ourselves free to transition to more sustainable lifestyles.

Stephenson reports the fascinating case of the surprisingly rapid adoption of photo-voltaic solar power generation by households in New Zealand. With no support from the Government, and active discouragement from power companies (offering prices for households’ surplus power one-third that of power from the grid), growing numbers of people installed PV anyway. Research showed that, when households changed their energy choices (activities) in this way, their motivations were driven not so much by environmental concerns, and rarely by the ratio of financial benefits to cost, but by a lack of trust in energy companies and a desire to break free from complete energy-dependency.

Over less than a decade the home PV movement forced government and power companies to include PV in their planning. External influences on PV adoption have switched from constraints on change to facilitators. The entire cultural ensemble has been re-directed towards more sustainable outcomes.

Stephenson also looks to the future with chapters offering advice to policy-makers and researchers on the use of the Cultures Framework to investigate and then encourage transitions to new sustainable ways of living. Here again, the framework’s superior breadth of vision holds great advantages over single-discipline analyses.

Prof Stephenson’s new book offers us the most complete understanding yet of the complex ways in which we are tied to our current lifestyles. But it also demonstrates the many ways in which we can release ourselves for the changes that we must make. Humanity’s response to the global climate crisis is a little more hopeful as a result.

Colin Campbell-Hunt is an emeritus professor of business, University of Otago.

The book

The book

- Culture and Sustainability. Exploring Stability and Transformation with the Cultures Framework, by Janet Stephenson. Palgrave Macmillan Open Access.