Sean Brosnahan takes a look back at Dunedin’s boy soldiers.

Many colonists brought with them to New Zealand a great pride in British military prowess. The 19th century had begun with military triumphs on land and at sea over Napoleon’s French forces, foreshadowing Britain’s dominant position in world affairs through the century. Almost a dozen British Army regiments served in New Zealand in the 1850s, with many soldiers remaining to settle in the colony. Veterans of other British military campaigns also emigrated, particularly survivors of the Crimean war. By 1858, at least 6% of New Zealand’s total European male population consisted of British Army veterans, ensuring that British military traditions would be a core component of emerging New Zealand colonial identities.

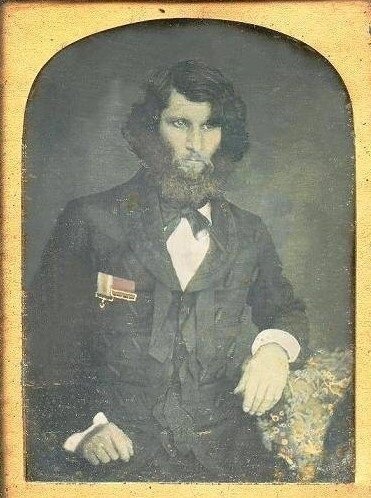

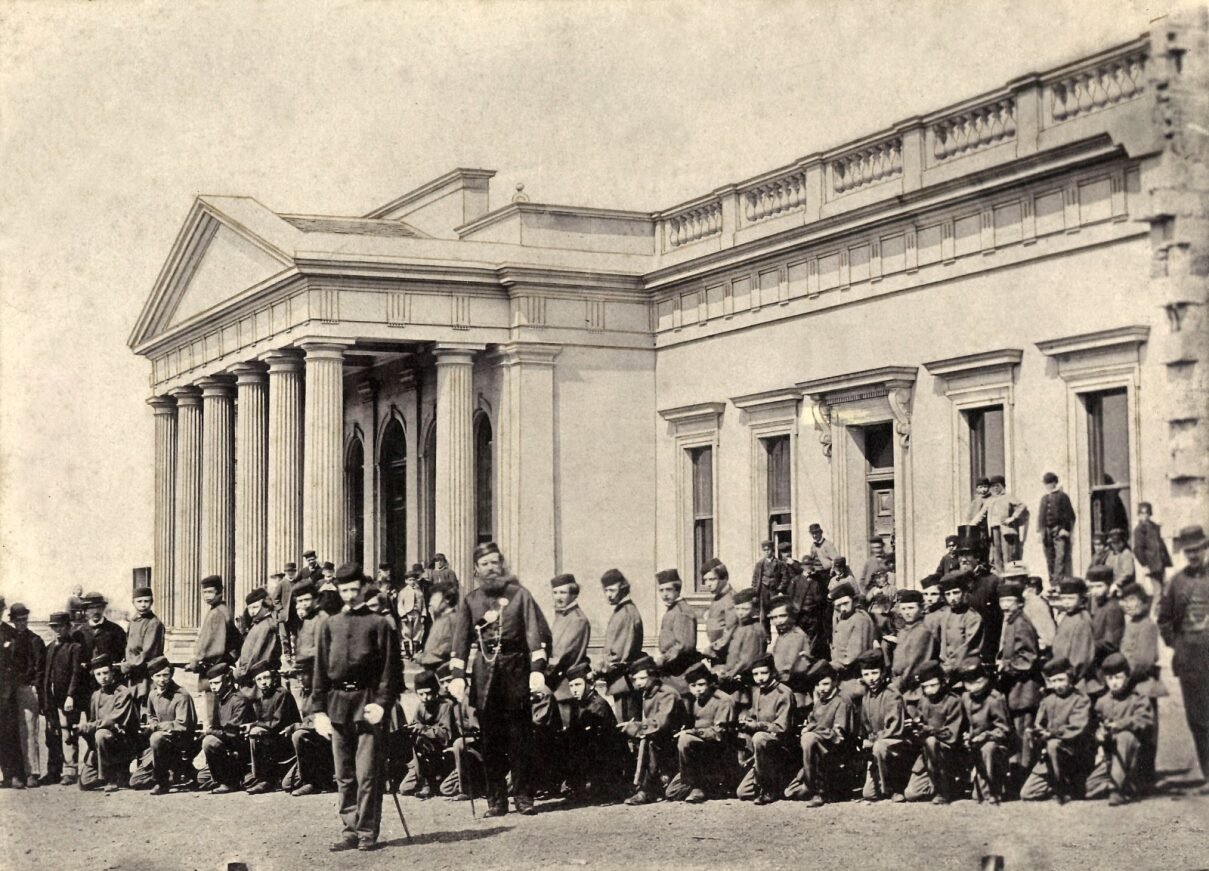

Little wonder then that the colonial-born generations were keen to take up arms in their turn. In 1864, senior boys at the Dunedin High School (now Otago Boys’ High School) petitioned the government to allow them to form New Zealand’s first school cadet corps. They were encouraged in this by the former Otago Provincial Superintendent, Major John Larkins Cheese Richardson, who became their honorary captain. Richardson had been born in India in 1810. After his education in England, he joined the Bengal Horse Artillery and was decorated for gallantry after the Afghanistan campaign of 1842. Retiring from the military a decade later, he came to Otago in 1856 to establish himself as a farmer.

The "old major" offered the cadets more than just encouragement. He also provided smart uniforms for his "gallant little phalanx" of boy soldiers and gathered funds to establish prizes for skill in shooting. In 1868, a newcomer to the school, Alfred Cox from South Canterbury, was awarded the top score and was presented with this high-grade Jacob’s .577 calibre Volunteer pattern target rifle made by George Daw of Threadneedle St, London. It was a distinctive weapon that was the creation of an idiosyncratic British soldier and colonial administrator, Brigadier-General John Jacob. He had made a name for himself in India by taming the wild northwest frontier and establishing the model township of Jacobabad in Sindh (in modern Pakistan), where his memory is still revered today.

A clever engineer and inventor, Jacob was critical of the accuracy of British service rifles of the day and set out to improve on them. He spent vast sums of his own money on his experiments, having guns made by some of London’s leading gunsmiths, and eventually producing a four-grooved rifle that worked with an explosive bullet of his own design. Another key feature was Jacob’s sighting system, using folding leaf sights with a five-inch ladder sight graduated to 1800 yards. It was their accuracy over long distances and their explosive bullet that were the distinguishing features of Jacob’s pattern rifles. Though they were never accepted for general service issue, they became popular with sportsmen, particularly big game hunters. Major Richardson had a close personal connection with Jacob, as revealed when another Jacob’s pattern rifle had been awarded as a shooting prize to the adult Volunteers in 1865: "[Richardson] saw that the prize which stood at the head of the list, and which Sergeant Devore had won, was a Jacob's Rifle. He remembered Major Jacob — of whom he was a schoolfellow — many years ago, as one of the most distinguished officers of the Indian Service; and he trusted and believed that the possession of this rifle would induce emulation of the soldierly qualities which so distinguished that officer."

Cox never got to go to war, and he doesn’t seem to have kept up his soldiering or his target shooting beyond his school days. He returned to South Canterbury and became a stock and commission agent in Temuka, involving himself in numerous sporting, civic, business and social endeavours in that district. He died at the Seacliff Asylum near Dunedin in 1893, aged 42. His younger brother donated his trophy rifle to the museum in 1932. Many later, OBHS cadets, however, would put their training to good use in military service in New Zealand and in numerous overseas conflicts before the school’s cadet programme ended in the early 1970s.

Sean Brosnahan is Toitū Otago Settlers Museum’s curator.

![Alfred Cox’s prize rifle. Photo: collection of Toitū Otago Settlers Museum [1932/9/1-1, the rifle]](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/story/2024/03/soldier1932.9.1-1-light.jpg)

![Major Richardson. Photo: collection of Toitū Otago Settlers Museum [CS/10434-1; Box A-446]](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/story/2024/03/soldierrichardson.jpg)