As a performer and educator, Honor McKellar has left a remarkable musical legacy in New Zealand.

Initially as a opera singer, then latterly as an inspirational trainer of some of the country’s finest singers, Miss McKellar packed an awful lot into her 103 years.

Although the breadth and depth of her influence was vast, one moment perhaps sums it up best: a Dunedin Town Hall concert in which two of the finest talents she trained, Patrick Power and Jonathan Lemalu, performed the duet from Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers as their teacher watched, bursting with pride.

Both singers now enjoy international careers, and both readily recognise the role Miss McKellar played in honing their talents so that they could succeed in a tough business.

Winifred Honor McKellar was born in Dunedin in 1920, the second child of Charles McKellar, a surveyor, and Ellen Jenkins, a Welsh woman who had come to New Zealand as an unpaid companion to Winifred Boyes-Smith, the first professor of Home Science at Otago University.

The McKellars married in 1918, when Ellen was 40 and Charles 46. They had two children in quick succession, and while Honor never married she was an integral part of brother Ian’s family and then those of his children, both as a revered relative and as keeper of the McKellar family history.

The recipient of a comfortable middle class upbringing, Miss McKellar was raised by a succession of maids as well as her parents: she remained close to some of them and in her student years worked on the orchard farmed by the husband of one of those maids after she had married and moved away.

By the age of 3 Miss McKellar was attending a Montessori school run by a friend of her mother, an institution which merged with St Hilda’s three years later. In 1927 she received her first formal music instruction — classes by Bessie Flavell in aural training and percussion, and eurythmics with Dorothy Dean.

She then attended the University of Otago, albeit self-described as utterly unprepared and lacking a work ethic: rather than attend first year courses in physics and chemistry she preferred to pursue another life-long passion, tramping.

While her marks, generally, remained a disappointment, the one thing Miss McKellar was succeeding in were the music classes she had taken on as optional courses to fill out the BA she had now embarked upon, but which grew to become her focus.

While World War 2 raged the thought of further music training further afield was out of the question but in 1946, after graduating with a BA in French and German and a batchelor of music — a degree she was encouraged to pursue by Otago’s first Blair Professor of Music, Victor Galway — Miss McKellar took the advice from visiting examiners and headed for England and the Royal Academy of Music.

As a student Miss McKellar forged a reputation as a contralto, but in London she was trained as the mezzo-soprano she was to be as a professional performer. A highlight of her London days was singing in a 1947 production of Vaughan Williams’ The Poisoned Kiss — at the party afterwards the composer taught her how to tango. Later that year a homesick Miss McKellar sailed home, receiving the sad news a week away from New Zealand that her father had just died.

After three years of freelance singing in New Zealand fellow performer Donald Munro, who had studied in Paris with baritone Pierre Bernac, encouraged her to head to France for further training.

While Miss McKellar enjoyed the classes she did not feel that they had improved her singing voice. She moved back to London, where after a dispiriting run of failed auditions she had the great fortune to meet the recently retired singer Roy Henderson, who took her under his wing.

"I thought he was mad, with the things he made me do," she said, but it worked and she was accepted into the Opera for All touring company. Miss McKellar was with the company for several years as it toured throughout the British Isles, her trademark role being the pageboy Cherubino in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro.

Upon hearing that Donald Munro planned to set up a similar company back in New Zealand Miss McKellar again returned home to join what became the New Zealand Opera Company.

In seven years with the company Miss McKellar became a household name, but in 1964 London called again. She found the music scene vastly changed from just a few years before, but found work firstly in the Glyndebourne opera chorus, and then the John Alldis Choir.

As well as a variety of choral work (including appearing on a Pink Floyd album), Miss McKellar struck up a working relationship with composer John Tavener, singing in his cantata Cain and Abel.

The former poor student also began teaching opera classes at various colleges and institutes in London and discovered that it was something she greatly enjoyed.

This revelation was Otago’s gain, as she applied for and secured the university’s first Lectureship in Performance Music.

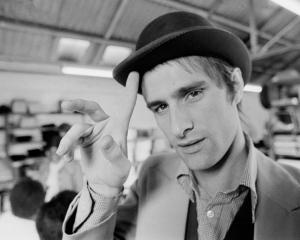

Her new boss, Prof Peter Platt, wanted to use Miss McKellar’s skills in opera in the university as well as in the community, which suited his new lecturer down to the ground. In her first year she sang in Albert Herring for Dunedin Opera Company with her student Patrick Power as Albert.

"She was so energetic, both physically with her bustling walk, and intellectually," Mr Power said.

"It was remarkable how she could be so strong in expressing her opinions without giving offence to those thus re-educated."

Other notable productions included Dido and Aeneas, Orfeo and The Dinner Engagement, directed by the recently deceased Louise Petherbridge (ODT 9.3.24).

Miss McKellar’s voice students took leading roles in these productions, often singing challenging roles. Nearly all were sopranos and mezzo-sopranos, drawn to Otago by her reputation.

Notable students included Marian Olsen, Maureen Smith, Jeanette Leigh, Beth Rask, Richard Madden, Sally Anderson, Jannette Finlay, Scilla Askew, Janet Roddick, Lin Jamieson, Fiona Nicholls, Sally Banks, and Mary Barton.

As well as coaching the cast and singing herself, Miss McKellar also performed a vital service for all Otago productions: she supplied the Anzac biscuits.

She was also involved with many off-campus musical groups, which included the Dunedin Opera Company, the Gilbert and Sullivan Society and the Southern Opera Ensemble.

In 1985, having reached the age of 65, Miss McKellar was obliged to retire from the university but it did little to slow her down.

She became a champion age group golfer, tramped in the Himalayas, recorded extracts from the newspaper for The Foundation for the Blind, took up tai ch’i, was chorus mistress and occasional lead performer for the Dunedin Opera Company, and also continued teaching.

One of the students who trudged to her Highgate home for private tuition was arguably the finest singer Miss McKellar trained, Jonathan Lemalu.

"I was a nervous teenager taking my shoes off in the corridor beside her golf clubs, stepping into her music room overlooking her burgeoning rose garden," he said in a tribute read at his teacher’s funeral.

"I am still today very much a student of Honor, heavily influenced by her joy, humour and humility, and I aim to encourage and empower the students in my care just as she did with me. Honor’s unique gift lay in making the complex and foreign seem simple, achievable and relatable — freeing stories from their pages with a joy and theatre of words, sounds and unlimited imagination.

"All I have achieved in music is indelibly linked to her care and respect for me, my career and wellbeing. As one of so many who have been touched and influenced by your light, thank you Honor."

Mr Lemalu’s fondness for Miss McKellar was replicated by his former teacher, who avidly watched the progress of his opera career from afar and treasured their reunions when he returned to Dunedin.

Miss McKellar’s life-long service to music and musicians was recognised in the Queen’s Birthday Honours in 1989, when she was awarded a Queen’s Service Medal.

Miss McKellar remained highly active and independent into old age, only grudgingly moving into a second story apartment in the Yvette Williams complex where, typically, she swiftly started a choir group.

Her final public performances were recitations of well-known poems with musical accompaniments. Although she was not singing, her delivery was perfectly timed, full of character, and every word distinct.

Honor McKellar took her final bow on February 2, dying aged 103.

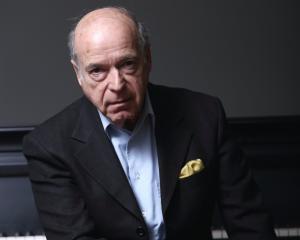

Reviewing her career, former colleague Prof John Drummond said what made his friend so remarkable was that she saw the delivery of a song, or an aria, as the sharing of a complete human experience, and that is what audiences received from her.

"We will remember her total dedication to her craft, her discipline, her quiet way of just getting on with the job, her unflappability in crises, the way she cared for all those she worked with, her sense of humour, the way her voice broke into infectious laughter, and her delight in the ironies of life."

— Mike Houlahan, with invaluable assistance from Peter McKellar and John Drummond.