On a road trip with poet Sam Hunt in the 1970s looking for somewhere to live and work, Robin White "fetched up" in Dunedin.

It took only one trip out to Otago Peninsula for White to know that was where she would like to live. A couple of years later she found a house in lower Portobello for a "princely sum of $1500" that, she says, suited her perfectly, meeting her primary criteria of being close to the sea.

Her view was Harbour Cone.

"It became an anchoring point for me visually in terms of place."

She had met Hunt when she was fresh out of Auckland art school in the late 1960s and became his neighbour at a little inlet off Paremata Harbour, near Wellington, named by Hunt as Bottle Creek — "for obvious reasons".

"He offered to find me a place to live, which he did. The little place I had to live and work in became just too small."

After failing to find somewhere else, the pair headed off on a road trip, finally arriving in Dunedin.

It was while living on the Otago Peninsula she invited Hunt to visit and the idea for her famous painting Sam Hunt at the Portobello Pub (1978) was born.

"There are a lot of changes in medium and approach to making images but the constant thing has always been the reference to place and circumstances in which I live," White (76) said.

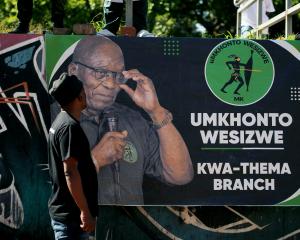

That place changed dramatically for White when the family decided to move to Kiribati, the former Gilbert Islands, after being invited there to assist and support its Baha’i community.

"We were members here in Dunedin of the Baha’i community. Nobody was offering to go. So out of the blue, we were approached. For me it was a wonderful adventure. So off we went."

She soon realised it was not going to be possible to continue working in the way she had. Living in a village in a traditional home, with a thatched roof, meant traditional painting materials were not suitable.

"The canvas and oils I had packed had to be put to one side and I had to rethink my approach."

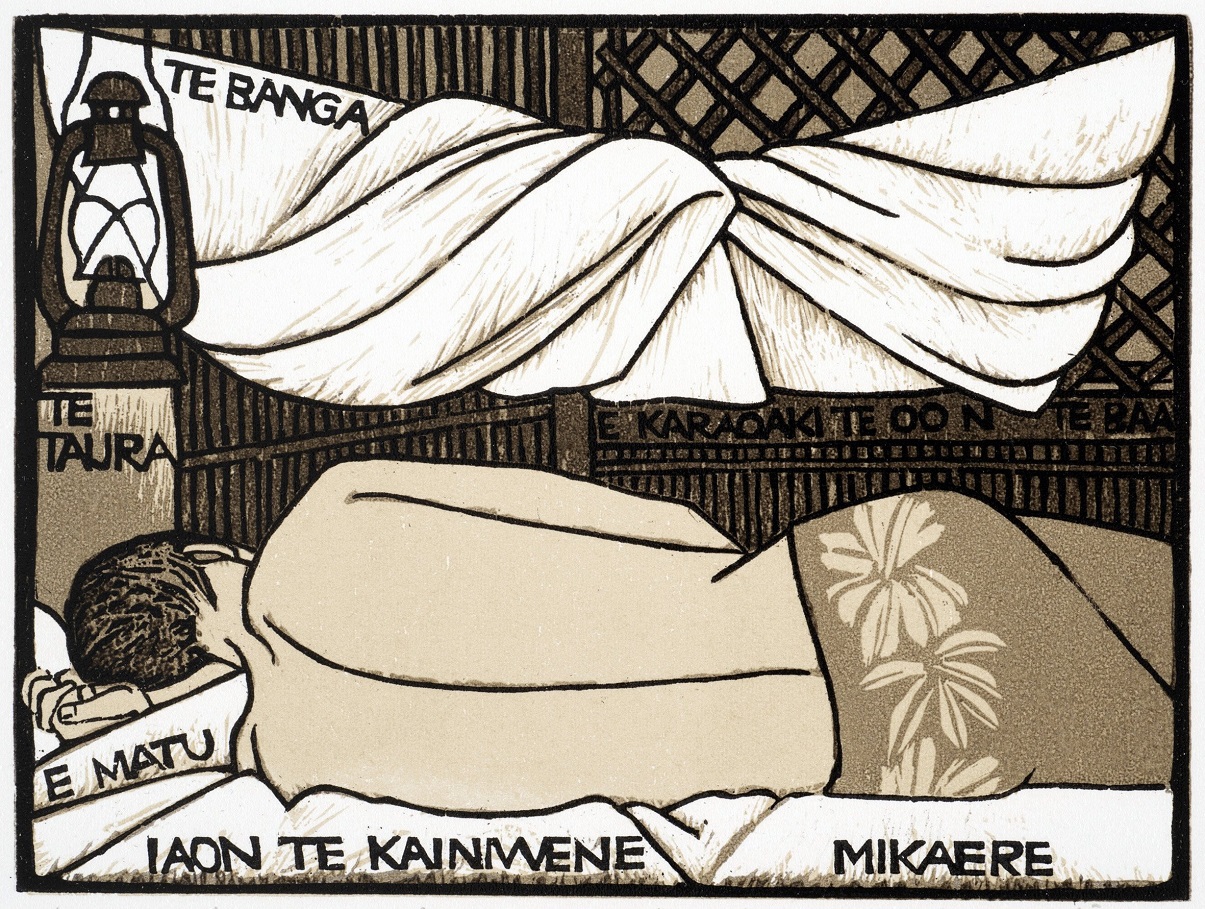

As she began to learn about the culture and language of her new home, she started drawing.

"That process of adaptation is recorded in the Beginner’s Guide to Gilbertese, where I’m learning how to make a wood cut because the wood was available and I happened to have some carving knives. So I thought ‘This is going to suit the situation I’m in, rats aren’t going to attack and insects won’t be bothered’."

White fell in love with Kirabati.

"That became my place. We were there 17 fantastic years. I learnt so much while I was there."

White returned to New Zealand with a new body of print works.

On the journey back to Kiribati in 1996 she learned fire had destroyed her home and studio there.

"All I had was in a suitcase with me."

The family was offered a room to stay in and she began to think of ways to continue working on her ideas.

"I realised I had only what was available locally."

There is no tradition of painting in Kiribati, as the art was in women’s weaving. White began working with them, creating her first works on woven pandanus-leaf placemats — New Angel (1998) is based on logos for basic products available from the island’s local stores.

"I got hooked on it, that way of working. So I started to look for other opportunities."

Soon after, White and her family returned to New Zealand. Her children had been living with a Kiribati family while attending high school in Masterton and White and her husband wanted to be closer to them.

"It was a way of maintaining that connection with their Kiribas family. Our kids’ first langauge was Kiribas."

Her first works were an effort to address the effect of colonisation on Māori. She worked with a young Māori "tagger" who came into her studio to tag the wool bales she was using to create work.

"The idea of the wool bales was to make the medium as much part of the message as the image."

White also learned of a prisoner of war camp in Featherston where Japanese and Koreans were interned during World War 2. In a "cultural misunderstanding" 48 Japanese soldiers died in a shooting incident.

"My father was very anti-war and a member of the Peace Council and he used to take me to meetings when I was just a kid."

At one of those meetings she learned about the bombing of Hiroshima, which "haunted" her. She had always wanted to travel to Japan, and did so at the invitation of a Japanese painter. There she sought out a Japanese calligrapher to write into her painting.

"We became friends and she agreed to do it."

On her return to New Zealand, White found she was still "hankering after" the Pacific. An opportunity to work with a Fijian friend, Leba Toki, whom she had worked with before, came up. In Lautoka, Fiji, White worked with Toki and her sister-in-law Bale Jione, producing Teitei Vou (A New Garden) (2009).

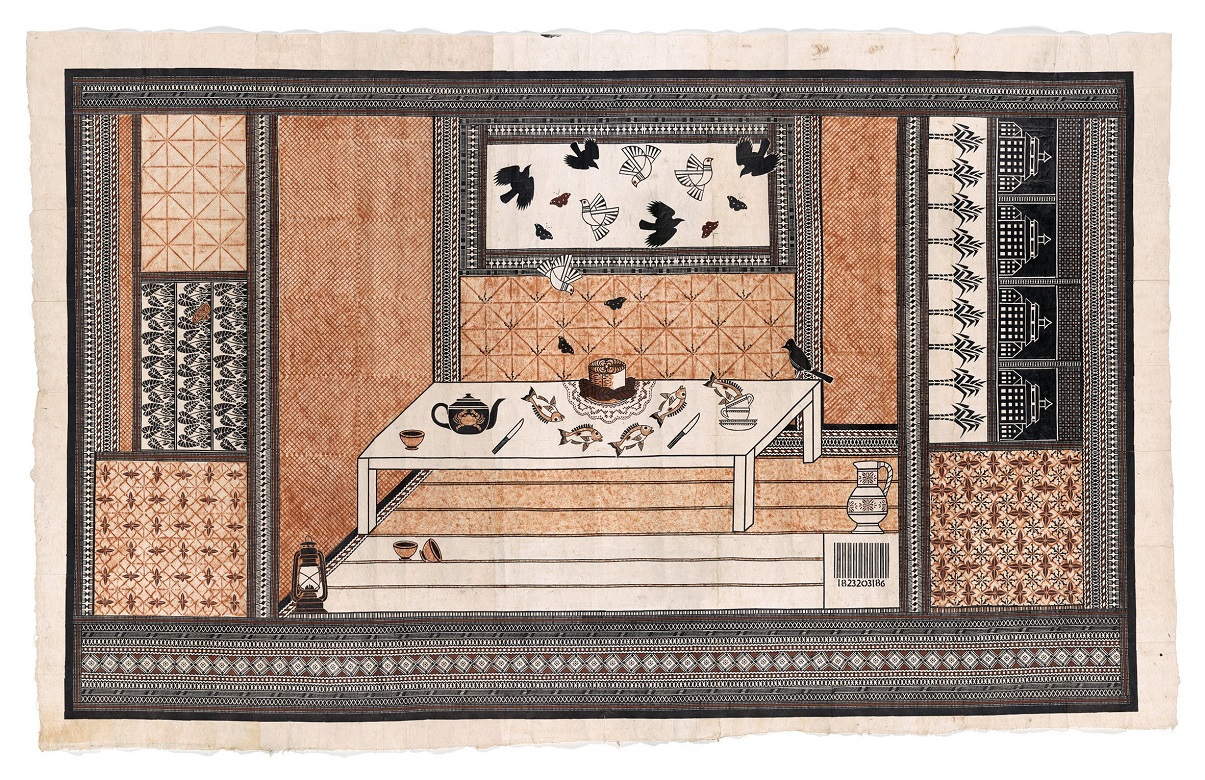

"Through these works I made with Leba I got to know about how the process of image making on tapa and also learnt from Leba about the history of making tapa and that it was closely associated with tapa in Tonga.

"We had this dream of bringing the two traditions back together again as they had been pre-colonial times."

"That was my opportunity to learn the Tongan approach to working on tapa."

White, Fifita and Toki came together again to produce another series of works. In the Fijian tradition, stencils are used to apply the images but in Tonga they create templates which are then rubbed and hand-painted over the top. The large tapa works incorporate both styles, along with White’s images.

"When it comes to the visual elements which are part of the narrative of this, it is when I design — the teapot, those birds, I design and cut those stencils."

White’s most recent work is a return to drawings, notes and research she was doing back in 1997 when she was still living in Tarawa in Kiribas.

"The idea got disrupted by leaving Kiribas and going to New Zealand."

The water colours, based on things she encountered on a daily basis in Kiribas, are just a "trial run", she says.

"This is me just experimenting to see how the drawings might look when they are enlarged. They’re really elements of a work in progress."

To see:

Robin White: Te Whanaketanga, Something Is Happening Here, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, until June 25; After Hours Tour, April 20 6pm-7pm.