As a city person, photographer Marti Friedlander was endlessly curious about rural life.

The renowned New Zealand documentary photographer, who died in 2016, aged 88, came from London to Auckland in 1958 after marrying a Kiwi, Gerrard Friedlander, and while urban environments were her norm, she enjoyed travelling through rural areas.

Art historian Dr Leonard Bell, an expert on Friedlander’s work, says she was struck and impressed by the down-to-earth manners, quiet strength and resilience of farming people in New Zealand.

A selection of original silver gelatin photographs of rural South Island images are being shown for the first time at Starkwhite in Queenstown, including one of her "famous" photographs of sheep being driven down a road in the Eglinton Valley early one morning in a cloud of dust.

"Sheep looking back very intensely and quite beautiful really. I think as I put it, ‘sentient animals’. That’s a photograph that has generated so many responses over the decades."

The Friedlanders often holidayed in the South Island — the Eglinton shot was taken on a holiday to Milford Sound — and she was fascinated by how different New Zealand was from where she had come from.

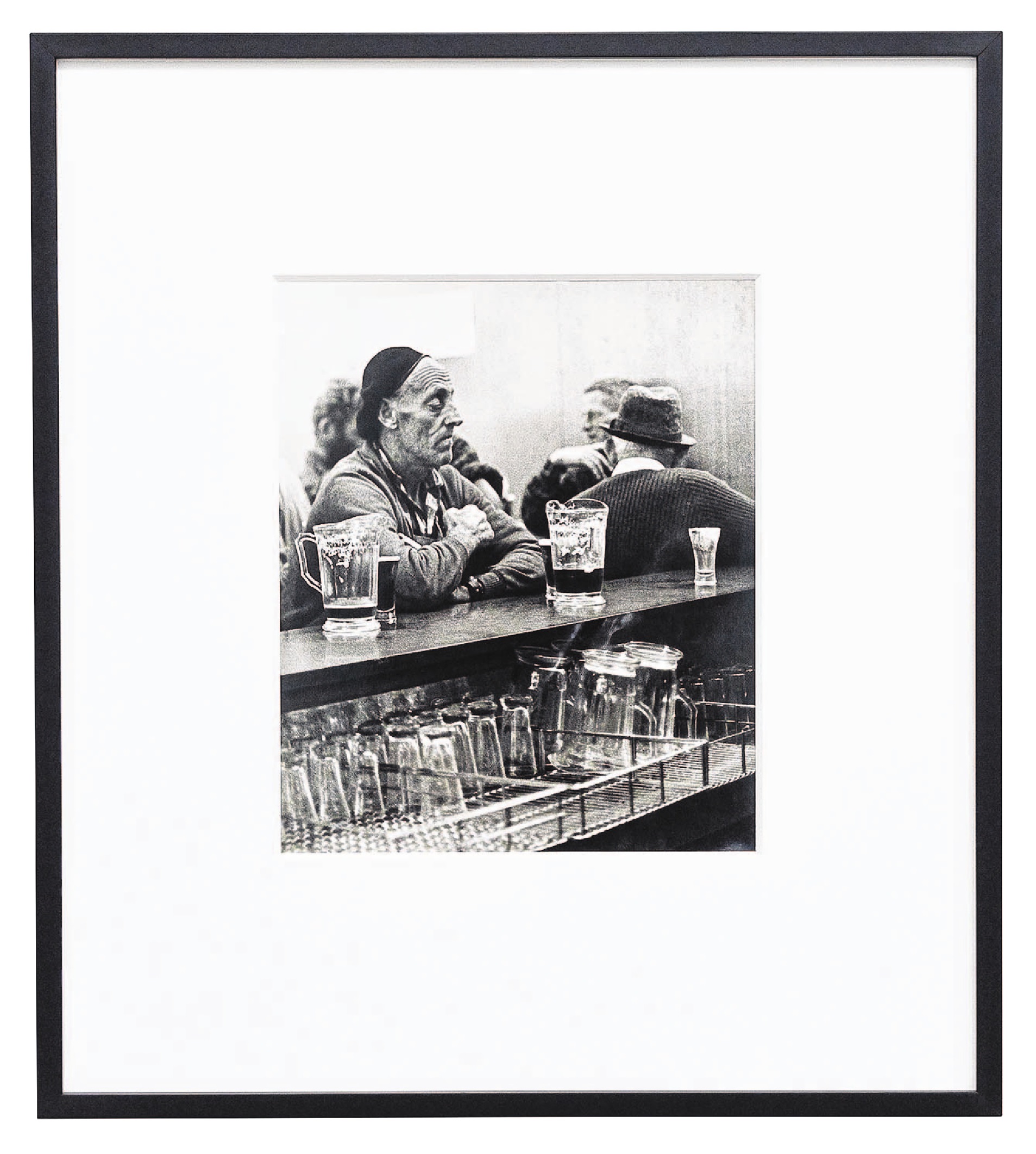

Another photograph shows a man in a public bar on Stewart Island. Back then public bars, especially in rural areas, were "no go" spaces for women.

"Going into a pub, such as in the Stewart Island, was probably something she couldn’t resist, to ‘break the rules’."

"It is a powerful image of isolation/loneliness in a crowd and of potentially explosive tension in a person. To me it’s one of the most extraordinary photographs she made over the years in the sense that obviously immediately it’s of a single man, but it could almost stand as a sort of metaphor for the unspoken, and they certainly existed, tensions more broadly, in New Zealand society at the time."

But that is not what Friedlander would have been thinking when she took the photo as she would have been focused on the immediate situation, he says.

"But she sort of worked often quite intuitively, very astute psychologically. So she picked up on qualities like that very, very quickly.

"So she could almost see the image that she was producing before she took the photograph."

As the author of a biography, Marti Friedlander (2009), and Portraits of Artists (2020), a book of 250 of Friedlander’s images of New Zealand artists, Bell has a unique insight into the photographer’s work.

He knew of Friedlander’s work as far back as the mid-’60s and went to the first public exhibition of her photographs in 1966 at a cafe in Auckland, a well-known artistic venue of the time.

But it was not until the mid-1970s that Bell met Friedlander, who was made a CNZM in 1998 and received an Icon Award from the Arts Foundation in 2011, in person. He was teaching art history at Auckland University and Friedlander enrolled in a few papers.

"So that’s when we first got to know one another. And we sort of had a good rapport and we became friends."

"One thing led to another. She wanted me to be her — I think the legal term is literary executor. In other words, to look after her photographs and documents and be responsible for them, effectively. Or how they’re made use of after her death."

He recounts being at her home to talk about her work and being asked to check under the bed in the upstairs bedroom to find a photograph.

"So I’d haul out a box and there’d be photographs I’d never seen before. The day before she died, Sylvia, my partner, and I were around seeing her, and precisely that happened. She asked me to get a box, which I never knew existed, and then there it was. It’s photographs I’d never seen before.

"So it was a creative chaos."

The bulk of Friedlander’s photographs are on loan in perpetuity to the Auckland Art Gallery and thousands are already available to look at online with more being digitised. The trust that oversees the works employs an assistant to do that work and check the information with photographs is correct.

"It’s a fantastic resource."

One of the biggest challenges as executor, he says, is protecting the photographs from piracy as there have been a number of instances in recent years of people trying to pirate the works and pass them off through online auctions.

"That’s one thing I have to keep an eye on."

"She had a long apprenticeship, if you like, working for highly renowned photographers in Britain for almost 15 years. Working in their studios, printing, touching up . . ."

This experience gave her "extraordinary" technical skills.

"She was very knowledgeable about photography and art, generally."

Bell is wary about presenting a picture of the perfect person.

"She was far from it. She was very witty and very critical of her own work. So she set herself very high standards."

But he considers what makes a great photographer is the working of the "eye, the mind and the hand in combination", which needs both training and innate ability.

"She had, to me, extraordinary ability to make an image which was striking itself and also sort of embodied more, a sort of intuitive sense of photographs.

"She picked up on what might just be sort of subliminal qualities very quickly. So she was very perceptive, both visually and psychologically.

Friedlander’s photographs continue to resonate with people of all ages. Some of her photographs are included in the school curriculum and are often requested for use in other productions. The trust also provides grants to low-decile schools to enable them to buy photography equipment for their classes.

"So they have a lively life, or a continuing life, which is good."

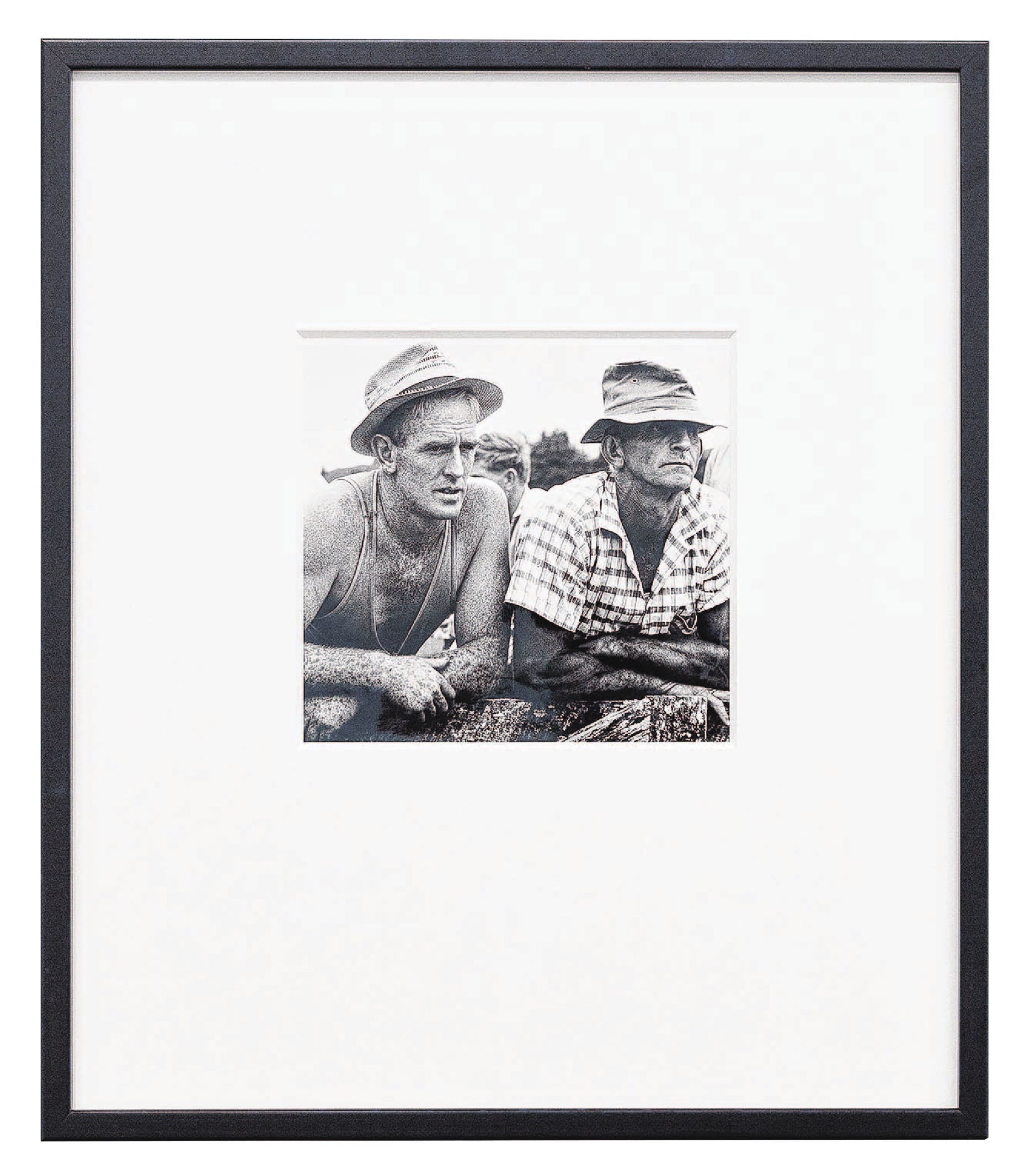

Part of the life are exhibitions of the original silver gelatin photographs such as Starkwhite’s "Southern Rural" exhibition in Queenstown, which features photographs such as Scratching Fence showing the tufts of wool on a farm fence, Smoko, of two sheep shearers in 1969, Farmers (c.1970) of two farmers in a riverbed and one of fantail taken c.1970.

"It [the fantail] is quite an unusual photograph, quite beautiful really."

It is a smaller selection extending out from last year’s retrospective "Starting Point of a Complicated Story" shown last year in Queenstown and Auckland.

In response to that exhibition, 100 prints of Eglinton Valley (1970) have been released for sale alongside this exhibition.

TO SEE

Marti Friedlander, "Southern Rural", Starkwhite, Queenstown, until mid-July.