At just 9 years old, Taloi Havini’s idyllic life on Bougainville, an island in the Pacific, was torn apart.

It was 1989 and water towers and pylons were blown up and roads blocked off by men with guns as martial law descended on the island.

"I didn’t understand what happening, but I could see fear in my parents’ and neighbours’ faces."

Her parents, Moses and Marilyn, who were seen to be dissidents after having raised the independence flag and due to her father’s job with the government, were forced to flee Bougainville with their children for Australia, as conflict between Bougainville and Papua New Guinea escalated over mining on the island.

They left behind grandparents and aunts and uncles, settling in Sydney and staying with her grandmother Havini (Nakas Tribe, Hakopeople). Her family watched what was unfolding in their homeland on television as civil war unfolded.

"It was strange ... It was a culture shock."

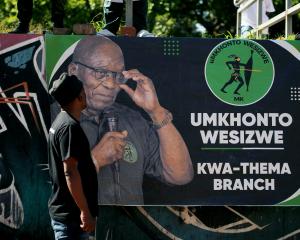

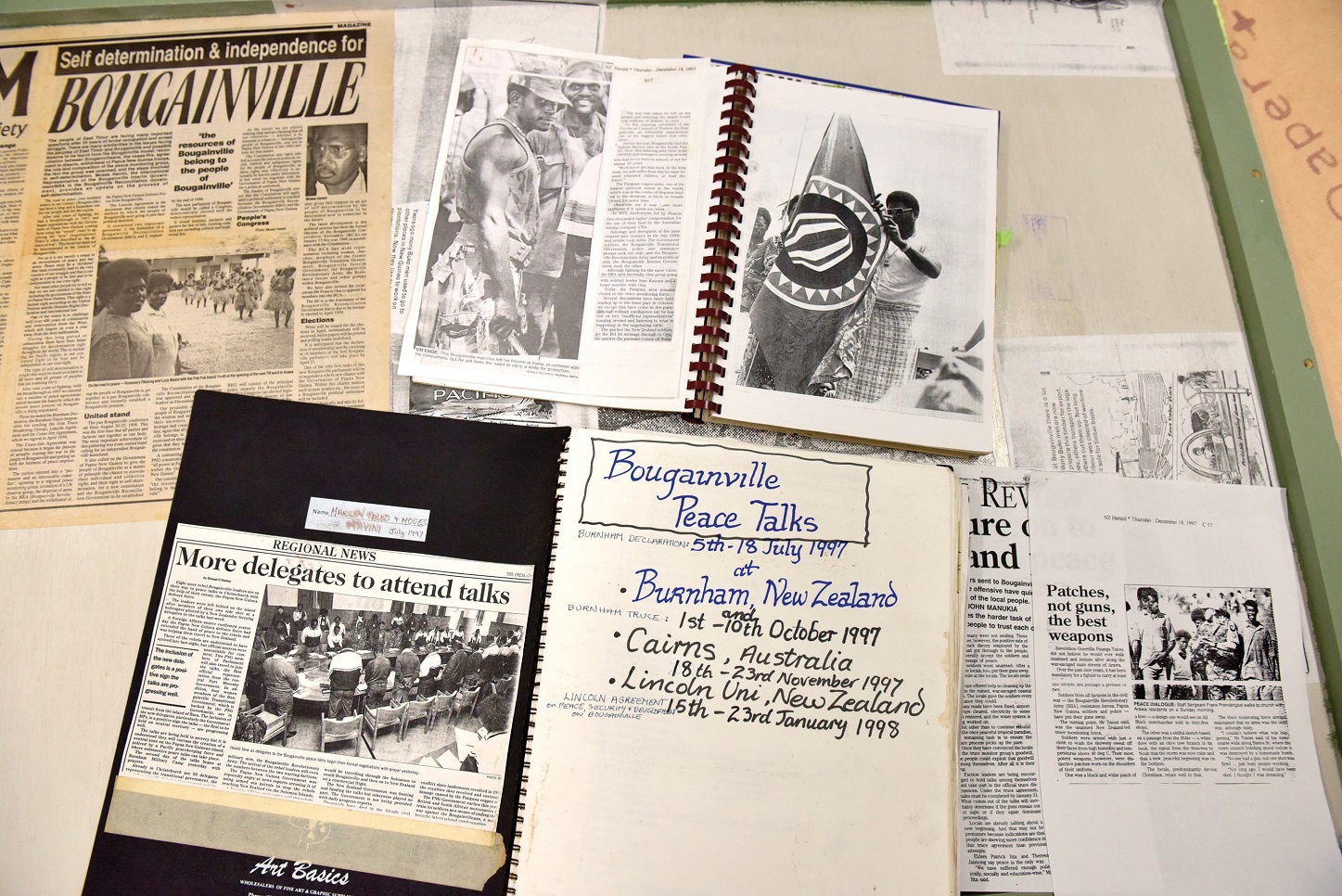

Her parents continued in their struggles for self-determination for Bougainville from afar. Then her father, who died in 2015, took part in ceasefire talks held at Burnham Military Camp, near Christchurch, in the late 1990s.

Those memories of her childhood and her parents’ struggles have stayed with Havini. So when she was invited to be Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s international visiting artist, it seemed the perfect time to explore her parents’ time in New Zealand as part of the peace processes and as part of Bougainville’s pro-secessionist movements in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as New Zealand’s strong links to her homeland.

"I wanted to explore that through an artistic and family lens. My father chose to work in law and activism [which] turned into government, and my mother is a teacher who worked tirelessly with women to support the aspirations of our people, and I chose to be an artist and yet here we are. We have all come together in this residency exhibition."

Working primarily in video installation, Havini asked her mother, who is also a painter, to take part in the project.

"We are drawing on both our practices and meeting in the middle — physically in the middle of the exhibition, reconciling all these old and current and recent history documents that talk about the context of Bougainville, about how instrumental families and communities were, not just governments, in achieving peace.

"Yet while we have achieved peace, a lot is unresolved environmentally, politically, seeking justice for wrongs, for human rights abuses."

She has titled her exhibition "Shared Aspirations" to reflect how the word "aspirations" has come up a lot in her research for the exhibition.

"It’s an interesting title. The women of Bougainville have aspired for so much more for their community; my father used it in the ’60s-’70s.

Havini and her parents’ experiences are reflected in the exhibition, which features a constant loop of video footage she found that she, her father, and other family members had filmed over the years. There is also footage from friends who filmed witness accounts of the injustices that occurred during those times.

"Bougainville is known for its human rights abuses."

She has chosen to show the footage on an old television reminiscent of the one she used to watch in the 1990s at her grandmother’s home. The exhibition space is also painted a similar salmon-pink colour to her grandmother’s house.

"It’s amazing they had one [a TV] that old here."

A large table, based on the one seen in photographs from the Burnham peace talks, sits in the exhibition covered in press releases, documents, tapes and photos of events that took place around it.

Nearby in the corner is a little table, which represents the side events that take place around major negotiations, which might be as equally important but often do not get recognised.

In this case it reflects a story her mother told her of two women, one from each side — they had been forced to choose the side of the rebels or PNG — having a birthday on the same day and making a birthday cake.

"The Bougainville crisis did split families and relationships. I find when I talk to activists or people fighting for a cause, the side events are ... equally of importance — this is a homage for those events that are not in media, especially the women in Bougainville.

"It is a way to honour my parents’ generation. Sadly, like my father, a lot of people have passed."

While Havini has exhibited in New Zealand before, she has not shown this material previously. It is important to do so now, she says, as the island, whose citizens have voted for independence, continues its bid to secede from Papua New Guinea.

She fears that as the world seeks more precious minerals and deep-sea mining becomes tougher, there will be pressure to reopen Panguna copper mine. It was one of the world’s largest open-cut mines before it closed in 1989 after concerns about exploitation and environmental damage led landowners to sabotage mine operations.

"It’s timely to be asking questions, to have it put back on the table. Even though we had so-called successful negotiations, our aspirations have not been fulfilled."

As her mother is now in her 70s, Havini also felt it was time to revisit some of her stories of the past. She and her mother travelled Bougainville from Buka to Arawa, where Havini was born and which was home to her parents from the 1970s.

They photographed significant sites of degradation and unresolved issues along the way for her mother to paint — such as Arawa Bay, where local women pulled out a survey peg in one of the first protests against mining in the 1960s, and the site of the mine itself.

Working with her mother on the exhibition has been "beautiful", she says.

"She’s a living treasure. She designed the Bougainville flag, [and] has painted the island as landscape painter."

When Havini first visited Dunedin, she asked a curator at the Hocken Collections to see if she could look out anything to do with Bougainville. She found a colouring-in book her mother had designed in the 1970s for a cultural centre.

"I was like ‘Wow, my mum’s in the Hocken Library’ — there has been all these wonderful circles. Scratching beneath the surface has been wonderful."

Another discovery was that where she was staying in Dunedin was near the Corso building, which her father visited when he was seeking support for the independence cause from local Māori and Pasifika communities.

"It was a beautiful surprise. That made sense to me. I was a teenager at the time watching the hard work of my parents trying to receive humanitarian support for communities in Bougainville during the military blockade.

"It was a beautiful surprise to hear of the sacrifices of people like my father and the whole community here."

She acknowledges the hard work of Māori and Pasifika people in Dunedin who came to meet him to see what they could do.

Her family were able to go back to Bougainville in 1999 after the peace talks were successful. It was a long process that involved transitional agreements, ceasefires and unarmed peace monitors going to the island, something that had not been done before.

"I left as a child and came back as a woman."

Watching her parents’ struggle influenced Havini. As a teenager looking at what she wanted to with her life, she realised whatever she chose, it had to be something of value.

"They supported my decision to become an artist very much."

She had always known she wanted to be an artist, and attended art school in Canberra.

While her mother loves painting, Havini took to sculpting initially before she discovered a fascination with images and photo media.

As the first image-makers were white men, she thought as an indigenous woman she should be an image-maker who created new stories from her position.

"Why not be an author of that history of image-making?"

Doing the research had brought her closer again to her late father, who had always brought her back to her family, community and clan.

"He reminded me we come from a matrilineal society and as a woman I inherit the land and that it’s actually my responsibility as landowner to safeguard that.

"So lots of my practice is taking, head-on, extraction, and resisting the need to extract for money, and instead [aiming] to live off the land, which we do but it has always been threatened."

Earlier work talked about the poisonous tailings copper and gold mining spilled into Bougainville’s waterways and from there into the ocean, affecting not only the marine life but that of her people.

"Showing what is hidden is very important part of that work."

Another part of her practice is working with Bougainville’s cultural heritage, especially material culture held in overseas museums. Havini is working as a facilitator, finding out what material is held where and reporting back to the island.

"This has become quite important, especially since Europe began talking about repatriation. So it’s an important role I can do."

She hopes to learn from the efforts of Māori in having ancestral material returned to not just museums, but to iwi.

"That is so inspiring for our people."

These days Havini lives between Brisbane and Bougainville, and travels the world for her work.

"Mum is an artist and dad a cultural man — so art and culture, it feels, is my reason to live."

TO SEE

"Shared Aspirations", Taloi Havini: An International Visiting Artist Project, opens on Saturday, at 3pm. Havini will talk about her exhibition and research.