As David Biddick battled brain cancer he made it known that the “fuss” of a funeral was unnecessary.

The money saved will instead upgrade the facilities at Christchurch’s Riccarton High School, where Biddick was sports co-ordinator and coached cricket for a quarter of a century.

James Biddick, one of hundreds of former Riccarton students coached by his dad, said he was sports-mad, but the appeal was deeper than results.

“He probably took more pride in the growth of the student off the field or outside of the sport than the performance,” James told the Herald.

“He’d always update me on how the team was going, but he’d just as often talk about how a former student is now going to medical school, or that someone’s just got married, or had kids, whatever it might be.

“Those were the bigger highlights, I think, for him.”

James said his father was a “huge people person”, whose job never felt like work. He based it around old-school values, including “If you’re going to do something right, then make sure you do it right.

“He could be hard on kids that needed to hear a hard message, knowing that it was going to benefit them in the long run.”

Cricket appealed for its encapsulation of some of those life lessons, James said: “Being part of something bigger, being a team member - not everybody can bowl at the same time, not everybody can bat at the same time. And, on some days, it’s not your day, either.”

His past students include Cole McConchie, a captain of the Canterbury cricket team and all-rounder who has played for New Zealand.

David retired as sports coordinator in 2018, and gave up coaching in the months following his diagnosis of Stage Four brain cancer in December last year.

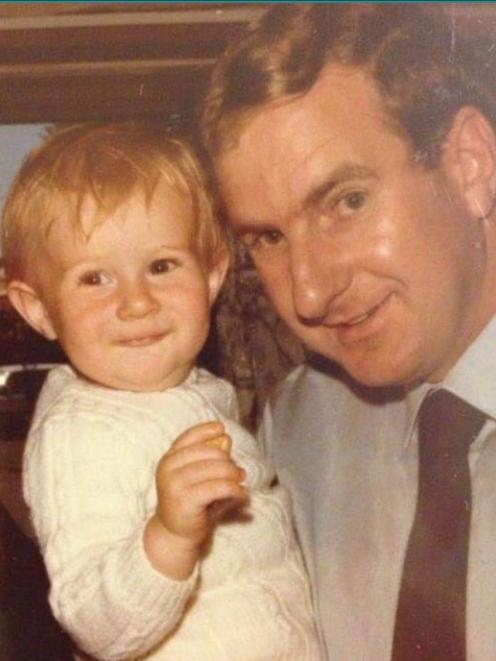

He died on November 30, aged 76.

He is survived by wife Elizabeth Biddick, son James and his wife Lara Brian, his daughter Anna Koster and her husband Dirk Koster, and their children Ava, 7, and Noah, 22 months.

David was clear that he didn’t want a funeral. James’ friends suggested raising money for his beloved Riccarton High School, a co-educational school lacking the resources of Christchurch’s more well-heeled state and private schools.

A Givealittle was established, aiming to raise $30,000 to upgrade the grass cricket pitch block, improve the playing field, and build a viewing area for players and spectators.

The Biddick family put in $7500. The total is currently over $12,000, and the messages accompanying donations have deeply moved the family.

“Mr Biddick was the heart of sport at Riccarton for many years. Our family thanks him for his support of all students,” one family wrote.

“An absolute legend and the backbone of RHS sport - an incredible man who will be greatly missed by so many of us who were fortunate enough to benefit from his kindness and passion for sport at our school,” a former student commented.

“His life lessons went far beyond the cricket pitch and will be forever lasting in the generations of cricketers that went through RHS,” commented another.

When the pitch and field are upgraded, an annual preseason cricket match will be held, with a team of old students taking on the First XI, in memory of David and as a way to connect different generations from the school.

“I’d best describe him as an absolute gentleman. Someone who gave so much, but didn’t ask for anything in return.”

Phil Holstein, who spent 19 years at Riccarton including as its principal, said the loss of his friend was hard to process.

The school’s motto is “learn that you may be of service”, and David epitomised that, Holstein said - from spending hours securing funding for sporting uniforms, to organising trips and helping coaches, all so his students got the most possible enjoyment.

“I was in awe at what he did, all for the good of others. He was a man of standards - he had very high expectations for himself, and he tried to grow that expectation in young people.”

James, 41, has lived in the United States for the past eight years. A trained lawyer, he works at the University of Notre Dame as a student athlete career development programme manager.

The role requires him to talk to athletes about their profession and possible paths after their sports careers end.

“It’s similar to what dad was doing. You don’t set out to follow your parents’ path, but their influence can push you in that direction.”

That connection grew when he was forced to return home about three months ago, while a new US visa is processed (he expects to return in the New Year).

He took a temporary learning assistant role at Riccarton High School, and stepped into his dad’s old position as coach of cricket teams, including the 1st XI.

“A few weeks before he died I said, jokingly, ‘Last game this Saturday for the First [XI] Dad, we’re playing at home. Would you like to come down and have a look?’

“He turned, and said ‘Yes.’ That was the first time he had said anything in about a month.

“There was no way we could take him down. But he still had that energy… it really connected with him.”

These holidays will be hard, James said.

“It’s Christmas, which is summertime, which is cricket time - watching it, going down to the nets. It’ll be weird, without dad around.”

By Nicholas Jones