Villas can be found everywhere in New Zealand, large or small, grand or modest, single or double-storeyed, highly decorated or plain. Charmian Smith talks to architect Jeremy Salmond, one of the authors of a new book, Villa: From heritage to contemporary.

Villas aren't unique to New Zealand, but they certainly have their own flavour here, architect Jeremy Salmond says.

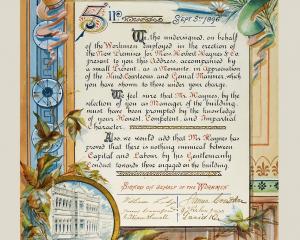

A grandson of Dunedin architect Louis Salmond (1868-1950), Mr Salmond grew up in a large villa in Gore, and now lives in one in Devonport, Auckland.

He specialises in the conservation of historic buildings and ways in which modern technology can assist in resolving conservation issues.

The style of house we call a villa came from overseas and was adapted to suit local conditions and needs.

Villas tend to vary in style around the country, he said.

They generally face the street with more formal rooms at the front and family rooms at the rear; rooms open off a corridor; numerous details such as bay windows, verandas, fireplace surrounds, archways, pillars, turrets, finials and gable ends, brackets under the eaves, embossed metal sheets, and other decorative features characterise them.

Many of these could be selected from timber companies' pattern books.

The Dunedin Iron and Woodware Company's catalogue offered a "cornucopia of choice - of mouldings, windows, doors, brackets, friezes, fireplaces, finials, balusters, newel posts, and the whole litany of the trade, right up to entire houses", he writes.

"Decoration is only elaboration of the basic form, and there's a fondness in the modern day to think you create lookalike villas by covering them with twiddly bits, but in fact the decoration was elaborating the right form.

Many of the decorative pieces actually had a purpose, such as boards or finials covering junctions to keep water out, or moulded architraves and fretted wood or cast-iron friezes to modulate the light.

Villas were often built of high-quality materials, especially timber, such as kauri, although it may have been painted or wallpapered over.

"If they are looked after properly, as one should any building, there's no reason they shouldn't endure indefinitely.

"I always say there are very few houses that are more than halfway through their useful life, by which I mean there are very few houses you couldn't actually fix up and keep going, especially wooden ones," he said.

However, although ceilings and floors can be insulated, there is usually a problem with insulating the walls satisfactorily without damaging the building, he said.

"The wonderful thing about the villa that has become a particular attraction for me is its capacity to change and adapt to have many different shapes."

Villas have a generosity of scale and space that most people can't afford to build today, and they are easy to adapt to modern ways of living.

They can be opened to the outside - his own villa has been opened out to verandas on three sides, he says - and modern amenities are easily built into them.

Many people rebuild the back part of the house, which was often a lean-to, into a more spacious family kitchen and living room, but it depends on the orientation to the sun and garden, and view, if any.

However, as an architect who specialises in conservation of old buildings, he finds it interesting that many other architects, when altering villas, put a completely different style of building on the back.

• Villa: From heritage to contemporary is a celebration of these 19th- and early 20th-century houses, lavishly illustrated with photographs by Patrick Reynolds, an essay by architect Jeremy Salmond, and stories of individual renovated and unrenovated villas by Jeremy Hansen (Godwit, hbk, $75).