RAF Pilot Officer W. H. (Bill) Hodgson (DFC), of Dunedin, was hailed as a hero for his wartime flying skills. Tony Eyre tells his story.

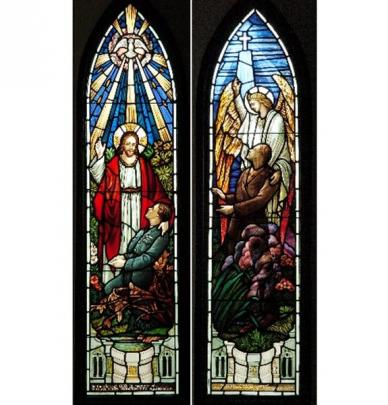

St Peter's Anglican Church in Caversham features some beautiful stained-glass windows, but two in particular catch the eye.

One of them depicts a Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot in blue uniform, with head raised, kneeling before the figure of a beckoning Christ whose hand gently rests on his shoulder. The pilot was 19-year-old Bill Hodgson, from Macandrew Rd, Dunedin.

As a child growing up in Auckland in the 1960s, I quite clearly remember Hodgson's framed photograph sitting on top of the piano in my grandmother's sitting room. His presence was always there, this formal portrait of my second cousin, in RAF uniform, smiling proudly back at me.

I was too young to know who he was, but looking back now, this picture among the ornaments on the piano was like a shrine, an image imbedded in the memories of my childhood.

Educated at Macandrew Rd School and King Edward Technical College, Hodgson worked as a radio technician at 4YA radio station before setting his sights on an air force career.

After some initial flying experience with the Otago Aero Club at Taieri Aerodrome and basic training at RNZAF Wigram, Hodgson left New Zealand in February 1940 to serve in Britain with the RAF.

Among those at the Dunedin Railway Station to farewell Hodgson was Betty Brough (nee Brown), a friend who was to keep in letter contact with him for much of his time overseas. Now 87 and living in Owaka, South Otago, she recalls two mementos sent to her by Hodgson - a gold lapel badge of air force wings and a cannon shell fragment, a souvenir from one of his many aerial escapades.

After receiving further flying instruction at the RAF stations based at Meir and Sutton Bridge, Hodgson was finally posted to RAF No 85 Squadron at Debden in Essex in May 1940.

This squadron of Hawker Hurricanes had suffered heavy casualties during the Battle of France and Hodgson was one of a number of replacement pilots brought into service in preparation for what was to become the Battle of Britain.

His squadron leader, Peter Townsend - who, in postwar Britain was to become royal equerry to King George VI and romantically attached to Princess Margaret - was soon to have good reason to nickname his young pilot officer "Ace" Hodgson.

As German raids over the English Channel continued to escalate, Bill Hodgson saw action for the first time on August 18th, 1940, while stationed at Debden. His No 85 Squadron was scrambled to attack a formation of about 200 Messerschmitts and Dornier 17s.

In the fierce frenzy of combat, Hodgson was credited with shooting down two enemy aircraft and damaging another. Of that skirmish, he recorded in his flying log, "Ruddy huns won't stay and scrap. Out of ammo, chased home by thirty Me.110s. My little heart went pitter-pat."

During the morning of August 31, the Luftwaffe launched a number of successful raids against airfields in the south of England. In the afternoon, attacks were made against airfields at Biggin Hill, Hornchurch and at Croydon, where 85 Squadron was now based.

Hodgson's Hurricane was one of 10 from No 85 Squadron doing interception control over the south coast when they were ordered to intercept an enemy formation of 30 bombers and 100 Messerschmitt fighters heading for the Thames estuary.

Despite being hugely outnumbered, the 10 Hurricanes dived to attack the German contingent and Hodgson was soon in the thickest of the fighting. He was soon to destroy a Messerschmitt 109 fighter and damage a Dornier 215 bomber in a head-on attack.

Earlier in the day, his squadron leader, Peter Townsend, had been shot down but was able to bail out with severe injuries to his left foot. Now it was Hodgson's turn. His Hurricane was hit at close range by an explosive cannon shell which blew up his oil lines and glycol tank.

At 20,000ft he unstrapped and prepared to bail out, but changed his mind when he saw to his horror the risk of his plane crashing into oil tanks at Thameshaven or the surrounding populated area.

Switching off his engine and keeping the flames away from the fuselage by a series of right sidesteps, he eventually got the flames under control even though glycol fumes and black smoke were pouring into the cockpit.

With great skill, Hodgson managed to avoid anti-invasion obstacles and make a wheels-up landing in an empty field near the Wickford village of Shotgate. An eyewitness to the crash-landing was a Mrs Billinge, who was watching the dogfights from her back garden and was able to offer the uninjured Hodgson a cup of tea.

According to her, Hodgson said "he was having a 'whale of a time' and couldn't wait to get up in the air and have another go at the so-and-so Germans".

For this feat Hodgson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). His flying log describes the reception he got later that day after walking away relatively unharmed from his damaged aircraft: "A major of the 2nd Glasgow Highlanders got me tanked. Boy, they treated me well."

Two days later, Hodgson was back in the air in a replacement Hurricane. The previous day, September 1, the relentless onslaught of the German Luftwaffe over the south coast of England had taken its toll on his squadron.

His flying log entry counts the cost of the carnage: "F/O Woods-Scawen `went west'; Sgt Ellis `went west', P/O Gowers bailed out, in hospital burnt; P/O Worrell bailed out, in hospital full of shrapnel; P/O Lewis crashed on aerodrome".

The death or wounding of seven of his squadron members on that day showed the grim reality facing the "few" of Fighter Command in their struggle to defend the skies over England against overwhelming odds.

With its pilot numbers severely depleted, 85 Squadron was given a much needed rest from the aerial battle. Despite his youth, Hodgson was now very much a veteran of the squadron and was involved in training new pilots in preparation for a new specialised role of night flying.

Late in 1940, Hodgson was taken off flying duties for medical reasons - his eyesight was probably affected by glycol fumes from his earlier crash-landing. Stationed back at Debden in February, 1941, the squadron had taken delivery of the first of the new night flyers, the twin-engined Douglas Havocs.

While on control tower duty one night, Hodgson was involved in a bizarre on-the-ground drama. After midnight, a bomber landed and taxied in front of the control tower. Hodgson came out to meet the disembarking pilots, one of whom put his arm on Hodgson's shoulder and addressed him in an unfamiliar language.

It was at that point Hodgson realised the pilot was German and the aircraft a Heinkel 111. The German pilots, suddenly aware of their navigation mistake, made a hurried exit to their aircraft, its engines still turning. While the Heinkel's rear gunner held Hodgson firmly in his sights, the aircraft taxied back to the runway and made a hasty retreat.

Ten days later, an excitement of a different kind saw Hodgson off to Buckingham Palace to be presented with the DFC by King George VI. Also receiving decorations that day were two other Otago airmen, Squadron Leader Trevor Freeman from Dunedin and Flight Lieutenant J. N. McKenzie from Balclutha.

Accompanying Hodgson to the investiture was Section Officer Rosemary Hollyer (nee Ross), a WAAF he had recently met at an air force dance. She was based at the clandestine code-breaking establishment, Bletchley Park.

Also from Dunedin, Ross had family connections to the well-known Dunedin woollen manufacturing company, Ross and Glendining Ltd. She now lives in Nelson, aged 95. In letters home to her parents in 1941, Ross recalled Hodgson's trepidation about the ceremony.

"He is simply terrified of going and has got out of it twice already. This time the CO says he's going even if he had to take him himself."

She reported the event to her parents in great detail, including the invitation to meet the New Zealand High Commissioner, Mr W. J. Jordon at New Zealand House: "He sent his official car for us and we sailed merrily along with the NZ flag flying from our radiator.

After photographing and a lot of fuss being made of us, Mr and Mrs Jordon took us to lunch at the NZ Services Club where we had a very happy NZ time."

It was back at RAF Debden in March, 1941 that Hodgson was due to attend a medical board to see if he was fit to resume flying duties.

Grabbing an opportunity to visit another WAAF he had met while stationed at Martlesham Heath, Hodgson hitched a plane ride with his good friend Flight Lieutenant Sammy Allard and another pilot, Sergeant Frank Walker-Smith, to pick up a new Havoc night-fighter.

Shortly after circling Debden Airfield, the plane was seen to stall, and then plummet to the ground, bursting into flames. Official reports confirmed that an inspection panel on top of the fuselage had become detached and flicked on to the tail fin, causing uncontrollable instability. All three fighter pilots were killed instantly.

Throughout the Battle of Britain, the young New Zealand pilot had defied death on many occasions - he had flown close to 150 operational sorties and it now seemed tragically unfair that his life should end in a flying accident as a last-minute passenger.

But war is never fair and the reality was that the odds of survival were severely stacked against Hodgson and the more than 2900 pilots who defended the skies over England in that summer of 1940. About 130 New Zealand pilots took part in the Battle of Britain. Of those, 13 were killed in that campaign, and by the time war ended in 1945, a total of 40 of those 130 New Zealand pilots had failed to return home.

Hodgson's exploits during the Battle of Britain were often reported in wartime editions of the Otago Daily Times. However, possibly because of official military censoring of wartime personnel movements, the Press Association releases that were fed into the local media were not always accurate.

One myth that was repeatedly published about Hodgson was that he had been shot down over Belgium and spent 12 days reaching the coast disguised as a peasant. Another myth concerned a much circulated picture, supposedly of Hodgson, standing beside his Hurricane which bore a painted crest depicting a number of bad-luck charms and the slogan "What the Hell" beneath it. Both reportings were cases of mistaken identity.

From the mixture of fiction and historical fact that has shaped Bill Hodgson's story, it is not surprising that this Battle of Britain pilot from Dunedin acquired a sort of hometown hero status, akin to a character out of Boy's Own Annual.

Even when the media accounts of his thrilling adventures were cut short by his fatal flying accident, the memory of his place among the few continued to be preserved after his death. One of the more unusual tributes was a 1941 song, Out of the Blue, composed by a Hanover St song publisher, Bert de Crewe, and according to its cover sheet, first performed by the South Dunedin Community Sing.

In June 1986, 45 years after Hodgson's death, a lone Hawker Hurricane fighter banked in towards the Essex village of Shotgate before roaring low over Wickford. The occasion was the unveiling of a commemorative plaque and the naming of a road - Hodgson Way - as a tribute to the young pilot who crash-landed his burning Hurricane near the site during the Battle of Britain.

Among the more than 100 civic guests and armed forces VIPs present was Hodgson's old squadron leader, Group Captain Peter Townsend, flown in from Paris to unveil the plaque to his wartime comrade.

Hodgson was buried in Saffron Walden military cemetery in Essex, many thousands of miles from his hometown Dunedin. His parents never did get to visit his grave. But his final resting place is not left untended.

In a remarkable act of solidarity and empathy, two residents of Shotgate, where Hodgson crash-landed during the Battle of Britain, have, since the 1970s, regularly made the trip to Saffron Waldron to place a wreath on his grave.

Back home, the two stained-glass images in St Peter's Church, Caversham are a moving reminder of the tragic consequences of war and its horrific impact on the lives of family members left behind to mourn the loss of their loved ones.

The second stained-glass window to catch the eye is one in memory of Bill Hodgson's brother Jim, a second lieutenant in the New Zealand Army. He was hit and killed by an army truck on a bridge near Balclutha in 1943. For Harry and Leonora Hodgson, the loss of their only two sons was indeed the ultimate sacrifice.

Remember them:

• A service to commemorate the Battle of Britain will be held at the cenotaph in Queens Gardens, Dunedin next Sunday, September 20, at 11am.