There have been many gifts of knowledge over the history of humankind which has forever positively altered the future.

It likely started with fire and the wheel. The printing press brought literacy and education to Europe in the 1400s. The internal combustion engine became commercial with the four-stroke engine 400 years later.

Antibiotics are up there as is the telephone, compass, internet and artificial intelligence, but few compare with what has been once described as the noblest triumph of them all.

It is an achievement that would rarely make the top 100 choices of human endeavour, yet has inadvertently done more for the wellbeing of humankind, yet is under threat as never before. We call it a property right.

It is a concept or a gift of law rather than a tangible entity. It gave a right to hold your assets against a king, a government or those who have acquired a fleeting authority over the ordinary person.

Governments in the Western world recognise a property right as a foundational value of our law. Without credit nor debit to one another, a property right, especially ownership in oneself is indisputable yet in too many parts of the world this vital concept is still subservient to political powers, either reclaimed or never given.

A mere 30% of the world has registered rights to their land and homes. Unsurprisingly, this 30% of citizens are from the most civil and wealthiest of countries in the world today due to the ability to own and trade property. It has allowed us all to enhance the wellbeing of an individual or family and in a free society, to find a way out of poverty.

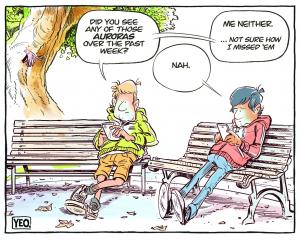

The right to hold property against all others is however becoming scarce, as populations are being constantly groomed into believing only governments and councils can deliver the nebulous concept of equality through forced distribution of private property.

A property right should never be accepted as something that can be reclaimed once given, yet today as never before, governments appears to believe they and only they hold the only key to prosperity through redistribution of property — in all its forms.

However, that which governments give, government can take away. The act of reciprocity is practised more and more as governments increase their ability to redistribute other people’s property.

Votes for a political party is often the trade-off for what is known in economic terms as a "taking" from others, yet to adhere to this concept is to revert to a cargo cult mentality, a false belief that somebody else should or will always provide. Incentives offered by governments are always offered to someone at something else’s expense.

History does offer some advice. If (in the eyes of some) property rights don’t matter, perhaps we should ask iwi how they view such matters. A rather rich irony permeates this issue as the property right of Maori to their land and property has been returned in some significant measure lately by successive governments as they take turns to restore that which was once wrongly taken.

The opposite is now occurring: the private property right of all others is subject to fleeting consideration by government and local authorities.

Some years ago, a director general of Conservation put it rather well at a public forum. Yes, he did agree that individual property rights were important. The problem is that we (Doc) haven’t decided which ones we should leave you with.

It is therefore increasingly clear that your home is not your castle if groupings can convince authorities that the need of the collective is greater than the actual owners individual property right.

Curiously, the advocates for the retention of heritage values of historical or even just old buildings, regardless of ownership, don’t seem to appreciate that civilisation is primarily based on the Western world’s liberal cultural heritage of the law.

Preservers of heritage are too often actively engaged in dismantling the heritage of our democracy, possibly without realising it.

If a company or a person wished to demolish or refurbish a house of some debatable heritage value, they required council’s permission. The owner must not demolish a house unless the protectors of our building heritage say you can.

No financial interest in the property by others is necessary . Even if the house is cold and uninsulated, interest groups believe they have a vested interest and therefore an equal right to a property.

Surely, it’s not what you demolish that matters but rather what you rebuild or refurbish. It cost the owners of a heritage building near Alexandra $640,000 for permission to weathertighten their asset. Councils pay no price for their wrong decisions.

It must also be said that some stunning work in Dunedin’s heritage precinct (the Exchange area) has been achieved, with buildings such as the old Donald Reid wool store becoming a delight to behold. Much of this area has wonderfully developed by private owners / developers where the heritage aspect is valued by the owner along with a complete need to change from the original use.

Should the heritage society and council wish to retain cold, uninsulated private homes buy the property, or at least the development rights to such property. It’s called a principled approach.

— Gerrard Eckhoff is a former Otago regional councillor and Act New Zealand MP.