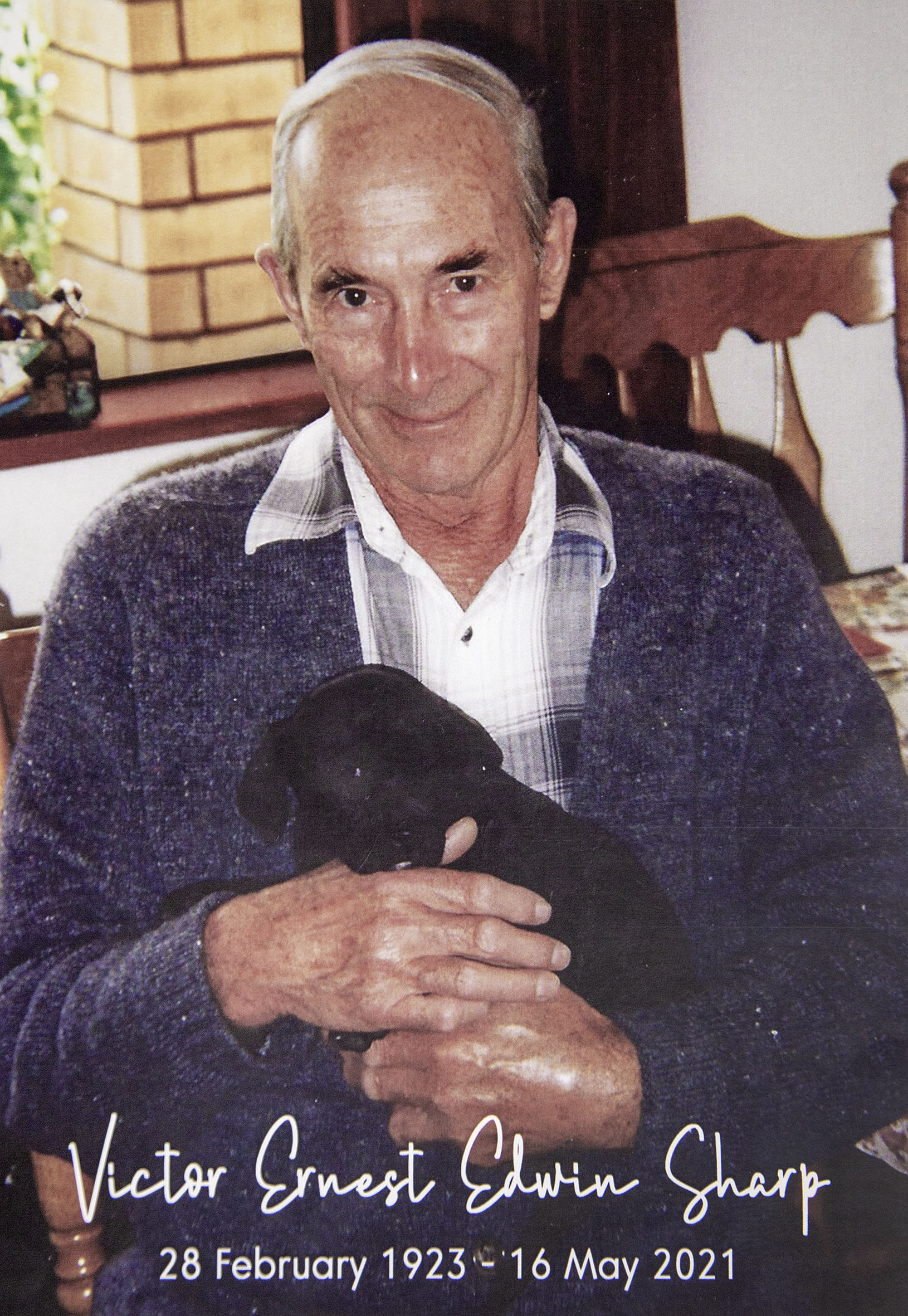

Staff Sergeant Victor Ernest Edwin Sharp’s entry with the Auckland War Museum online Cenotaph is scant in detail, a fitting reflection of his army service during World War 2. There is no photo attached.

The brief record indicates he was living with his parents at 31 Gayhurst Rd, Dallington, when he enlisted after working in civilian life as a radio serviceman.

Sharp, according to the Cenotaph record, joined the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force in 1944.

He was also listed as a signaller with Headquarters, 3rd New Zealand Divisional Signals, though New Zealand military historian Christopher Pugsley could not find Sharp recorded in the Headquarters and Communications history published by AH and AW Reed in 1947.

Later that day he interred at Avonhead Park Cemetery.

Sharp, service number 446826, died peacefully while surrounded by family members on May 16 at Ultimate Care Rose Court in Somerfield, Lower Cashmere.

His death notice in The Press provided the first indication Sharp was not a rank and file Staff Sergeant with its reference to "Z" Special Unit.

Victor’s youngest child Jonathan first told mourners his dad had been expecting to ship out to the Middle East in the winter of 1944.

“A suntanned, fit-looking captain arrived at Trentham and addressed all the men in groups, asking for volunteers in three categories: Radio operating/maintenance, navigation and diesel engine maintenance. Beyond this he wouldn’t elaborate.”

“It was all hush-hush. They spent time on Fraser Island and various places in Australia training in hand-to-hand combat, paddling in little canvas kayaks, learning explosives and the Malay language,” Jonathan Sharp said.

“This was his introduction to the Z-Special Unit.”

Predominately made up of Australians, the reconnaissance and sabotage unit carried out 81 covert operations in the south west Pacific theatre, including raids on Japanese shipping in Singapore.

One of these raids, Operation Rimau, resulted in the deaths of 23 commandos in either in action or by execution via beheading after capture.

Sharp's oldest son said his father rarely spoke of his time with the unit as one of 22 New Zealanders. Four were killed while on active service.

“Growing up I knew dad had been in a submarine and he used to sleep by torpedoes,” David Sharp explained.

“After WW2 those who were in it (the unit) were required to commit to secrecy for 30 years.

“It was only in later years that dad felt free to talk about it a bit more. Growing up I would have been both amazed and horrified at the types of things dad was trained to do.

“I knew he was good with boats and was very athletic. He tried to teach us how to vault over fences on the run. I now realise his training included many other things … the use of sabotage explosives, the various types of swift and silent combat.”

Victor Sharp would not dwell on his clandestine operations in the latter stages of WW2, though the submarine he was travelling in was attacked by Japanese pilots after an operation off the Sarawak coast was abandoned in January, 1945.

“The sea was so shallow, diving beneath the surface was no place to hide as the submarine was still visible from the air,” David Sharp said.

The contingent eventually transferred to an American submarine bound for Fremantle, a journey complicated by Sharp contracting yellow fever.

He was scheduled to go on another operation in August, 1945 but the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended hostilities.

England-born Sharp married Noeline, a former schoolmate at Linwood North School, in 1949. Their 67-year-old union ended when Noeline died five years ago.

Although Victor and Noeline enjoyed exploring New Zealand in later life, daughter Susanna said the family also visited Fraser Island, to see where dad honed his combat skills.

“It has been very fascinating learning more of this,” she said.

“I don’t remember dad talking much about his army life when he was young. He said he was in the army and had to be very fit.”

- Victor Sharp is survived by his sister Joy, four children, 14 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.