- Read book extract: Inside the dateline

Neville Peat is not the first writer in his family.

Among those to have picked up a pen earlier was one of the first of his line to set foot in New Zealand.

Sailing into Otakou in the 1850s the 11-year-old Scottish immigrant - one of a family of 10 children - was struck by the scene and recorded it many years later.

"He wrote, ‘we all thought the harbour very beautiful, bush came down to the harbour edge on both sides’," Peat recalls from memory.

As it has a tendency to do, or at least suggest the possibility, history appears to repeat in Peat’s new book, Home Is An Island, when he describes his own first impressions of a new land following a first sea voyage. In his case, it’s Stewart Island Rakiura.

"... in every direction the landscape is clothed in native forest, such a contrast for a lad who hails from the Taieri Plain’s summer heat and dryness. Stewart Island is New Zealand’s Emerald Isle, surely," he records in a book he describes as the closest thing to a memoir he’s likely to write.

That’s early on in the book, Peat recounting a trip in 1969 aboard the Heather George with the globetrotting MacLeod family, who were newly returned to New Zealand from seafaring adventures far and wide.

The mix of salt and shore proved formative for the "freshfaced young journalist".

"That really opened my eyes to all kinds of possibilities about islands," Peat says.

"That trip I made, within about a week, with the Heather George and the McLeod family, was really a launch pad for me to go and explore overseas, and go to all kinds of islands."

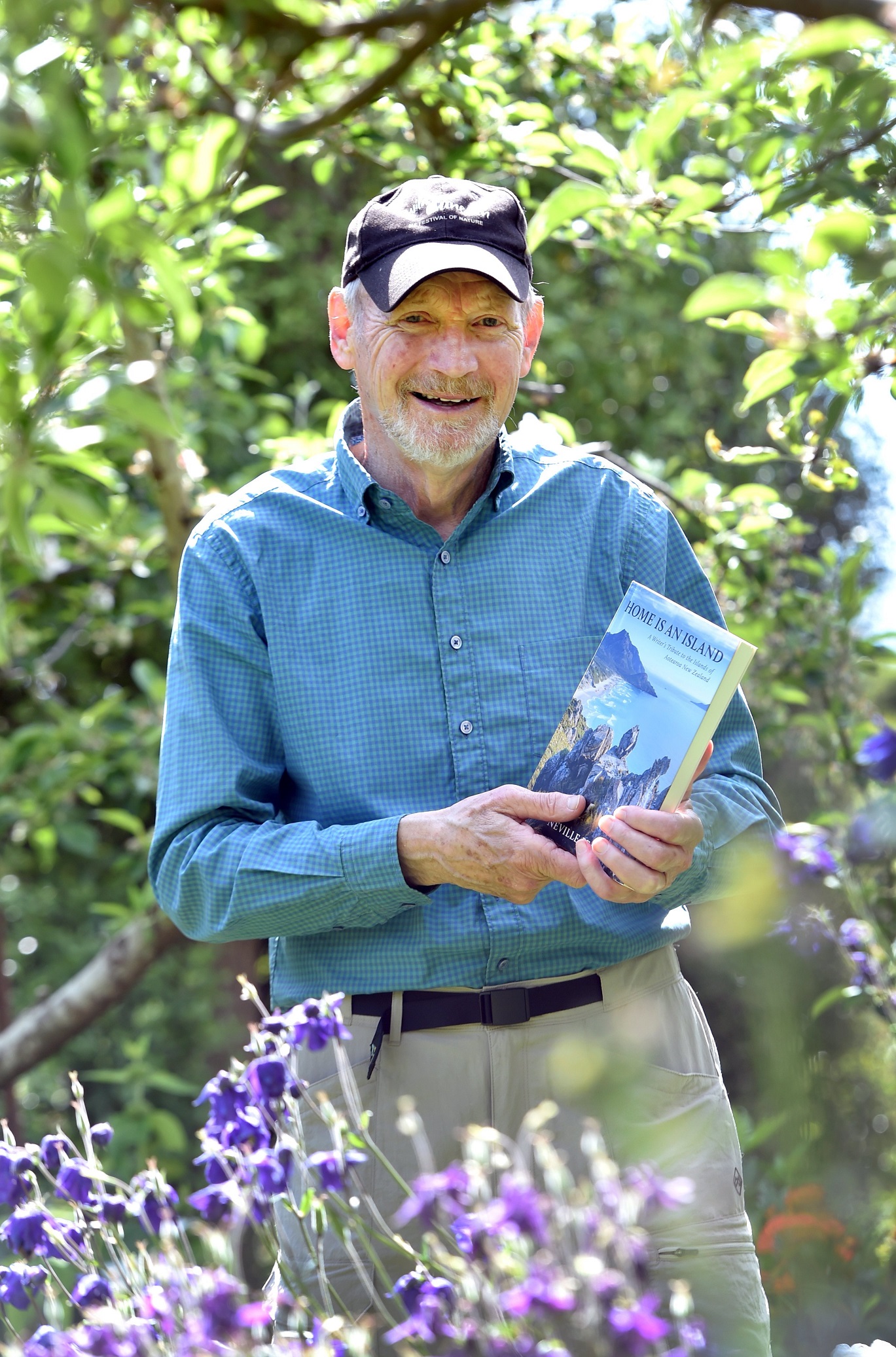

Home Is An Island doesn’t cover all the subsequent roving that Neville Peat, MNZM, the Broad Bay writer and photographer undertook. But it covers some territory and in doing so attempts to draw out an understanding or two about place, and our place in it.

"Well, I am over 70 now, so I don’t know how many more books are left in me," Peat says by way of preamble, sitting in the home office in which some of his more than 40 books have been written. "But for probably the last five years I have been thinking about writing something you could say was a memoir."

An all-inclusive wander through his busy life would have included many more waypoints but for cohesion’s sake, he says, he decided to keep it to just New Zealand’s islands.

"I thought I would just make it the New Zealand islands and pay tribute to them for the contribution, I suppose, they make to the identity of New Zealand, its nature, its wildness, its loneliness sometimes."

All the same, that gave Peat license to include the Tokelau atolls in the north - still New Zealand dependencies - then stretch his gaze south across 9000km of land and ocean to Ross Island in the Antarctic, making various diversions to take in the likes of the Chathams.

"In a way it expresses my interest in contrast and how islands can be so different in their nature and their formation, their flora and fauna and their human populations."

In the process, it recasts New Zealand as an archipelago, he says.

"As an archipelago in the Southwest Pacific, New Zealand has 11,000km of coastline open to the sea, with no shortage of islands. More than 600 are offshore or continental shelf islands, larger than one hectare and within 50km of the mainland," he writes in the book.

The stories that made the cut focus on both the geography and the people, and in all cases seem to hold up a mirror to the rest of us. Peat doesn’t do this in a heavy-handed way but at every turn the observations he makes provide a challenge.

The wildness was what attracted him to these places at first, he says, the apparently unspoilt bush of Stewart Island, for example, then the potential these pockets of land had preserved.

In the book he puts its this way: "As social and economic microcosms, islands invite us to view the global challenges of our age in new ways, with new insights."

In person he adds: "As I worked my way through the stories I thought, ‘they are telling us something here’. It is on a theme of sustainability, that so terribly overworked word. It is what we need to know to survive as humans."

That extends to the challenge of climate change, he says.

So, the stories aren’t just about the places, they’re very much about the people too.

His visit north to Tokelau - a dependent territory of New Zealand halfway to Hawaii - is a case in point.

"I think we have to adopt almost different language to get ourselves in a mindset to protect nature. Instead of looking at the natural resources as commodities we should be looking at it as communities, I suppose," he says.

"I think islands will teach us ways of achieving that kind of balance with nature.

"I am thinking particularly here of Tokelau, it’s three atolls, where there are traditional ways of sharing food and resources on the islands. It is a traditional method called ‘inati’. That and the more practical way of working there co-operatively when, say for example, a supply ship comes in from Apia and they have to have people off-loading."

Peat observed this co-operative effort in action in 1981, as part of his role as the publicist for New Zealand’s Official Development Assistance programme.

"In a striking example of community co-operation, practically all the able-bodied men were there to help," he writes in the book.

In those ways the relatively thin resources of the atolls are stretched to meet the community’s needs and the environment preserved.

The second half of Home Is An Island describes places that are now treasured as sanctuaries, Tiritiri Matangi, Kapiti Island, Anchor, Enderby.

"They are all a kind of network, those four anyway, that have appealed to me over the years for what they can do to remind us of what we have lost in terms of wildness and what we could preserve, especially in the bird world."

The story he tells about Hauraki Gulf sanctuary Tiritiri Matangi is some way distant as the albatross flies from Tokelau but not miles away in terms of community.

The opening section is subtitled "Lighting up a cause" and tells of former lighthouse keeper Ray Walter’s tireless work to transform the 3km-long island into an offshore sanctuary.

People flocked to the cause.

"Sceptics reckoned the project would get volunteers the first year and maybe the second but the novelty would soon wear off. Not so, said Walter," Peat writes in the book. "The third planting season attracted 1885 volunteers - a 60% increase -and 300 more worked in the nursery or on tracks."

Peat has some hands on experience closer to home with this sort of thing, as one of the movers behind the Orokonui Ecosanctuary above Blueskin Bay.

And Peat is involved in another close-to-home restoration project, on the almost island of Otago Peninsula, at Hereweka, Harbour Cone, where Lala Frazer and her Stop team are recloaking the volcanic cone in bush.

It has a very good chance of success, given the possum trapping the peninsula has seen in recent years.

"We have a couple of traps but the chew cards show no signs of possums," Peat says of his own backyard.

The uptick in birdsong has been notable.

His 11-year-old Scottish ancestor would probably approve.

Peat has a couplet from Robert Burns to close the distance between them further: "Gie me ae spark o' Nature's fire, that's a' the learning I desire."