Terrible conditions on the last dairy farm Brian* worked on did his head in.

Not the conditions of the animals; they were among the most well-treated he had seen. No, it was the way the workers were treated by the southern farmer that made him leave in disgust.

"We were turning up at the shed at 4am and not getting home until 7.30 or eight o’clock at night," Brian, speaking by phone from Christchurch, says.

"It was after calving. There was no real need for that sort of slave-driving.

"I heard stories of him having guys he had an issue with out there grubbing thistles with a head torch at four in the morning."

Although that farm was the worst, it is certainly not the only one with bad working conditions, Brian, who has worked on dairy farms for the past decade, says.

"Over the years, there’s been many occasions working without a contract, working on a salary, but well below minimum wage when hours are taken into account."

He has worked on farms in the North and South Islands and often encountered unfair treatment.

Especially bad, he says, is the treatment of migrant workers.

"Guys getting pushed around, yelled at, sworn at ..."

Brian has been trying to get employees from his last farm to speak up, but without success.

"The migrant workers are just terrified.

"They don’t want to ruffle any feathers because they are terrified they’ll lose their position in New Zealand."

The workers at that farm were given what looked like a good salary, often $55,000 or higher.

"But then he’d work the snot out of you.

"The other farmers in the area; you sit down at the pub and they all know. They all know it’s wrong, but no-one does anything, no-one says anything."

It is 30 years since the Employment Contracts Act turned New Zealand labour relations on their head.

In 1991, the Jim Bolger-led National Government, seeing the fourth Labour Government’s radical free market experiment had left it little to privatise and deregulate, completed the country’s neoliberal transformation with sweeping labour relations changes that massively swung the balance of power away from workers and trade unions in favour of employers and business interests.

The Otago official of the Amalgamated Workers Union, which covers industries including farm workers, Fisher recalls the pre-1991 days of the Agricultural Workers Act.

"Under that Act, we used to sit down with Federated Farmers and thrash out an agreement, with some degree of enforceability, for farm workers," Fisher says.

"So, when the Employment Contracts Act came along, that was the end of it for farmers, orchards, vineyards and shearers agreements.

"That’s what led, in our opinion, to the situation some of those industries got themselves into where it was the place not to work, so they started pushing for the need for foreign workers because they’d burned out the locals with breaches of wages, not paying holiday pay, not keeping hours of work ..."

That is only the agricultural sector. There was not a workplace or a waged employee throughout New Zealand that was not touched by the Employment Contracts Act (ECA).

Pushed through without consultation, the Act replaced the arbitration-based workplace relations system with one dominated by lawyers.

"Workers" were renamed "employees" who would contract directly and, largely, individually with employers.

Trade unions were stripped of independent legal status and union membership was made voluntary.

The ability to lawfully strike was severely limited.

"Voluntary unionism was ... not only a matter of principle but also a potent weapon for attacking the financial and organisational base of trade unions," Prof Anderson says.

Business interests had long been calling for more flexibility to help them compete in a global economy, Dr Stephen Blumfeld, a labour relations management academic at Victoria University, says.

"By ‘more flexibility’ they meant, ‘We need something that will keep wages down’," Dr Blumfeld says.

The ECA delivered.

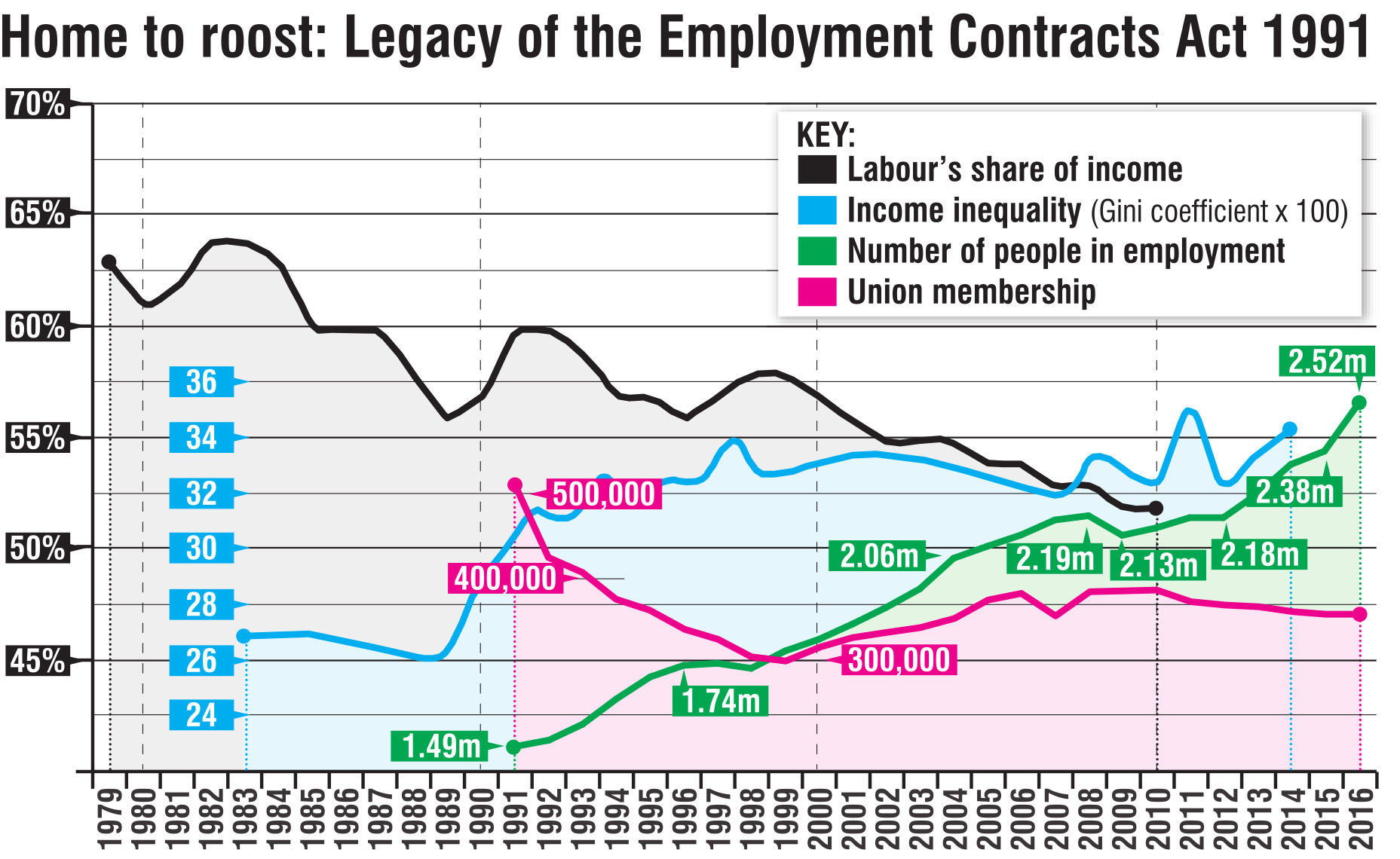

Union membership plummeted. During the 1990s, unemployment hit 12% and real wages declined by 25%. The labour income share, that is, the share of national income paid to workers compared with the share paid to the owners of capital, fell markedly. Inequality began to blossom.

Was a shake-up as radical as the ECA needed?

Dr Anderson says by the late-1960s New Zealand’s heavily protected economy, which supported the arbitration system, was coming under pressure from market changes overseas. Add to that the oil shocks of the 1970s and inflation ratcheting up prices and wages; the result was that the whole economy, including the labour market, was changing.

Compulsory union membership was also becoming increasingly unpopular, pushed along by a "Reds under the beds" union-knocking campaign by Prime Minister Robert Muldoon

Dr Blumfeld says even in labour movement circles people admit that by the 1980s some sort of change was needed.

"But none would say the ECA was the way to go," Dr Blumfeld adds.

There have been changes since the ECA. Most notable is the Employment Relations Act (ERA) 2000 and, four years later, amendments to it. The ERA and its amendments contained two important changes; the role of unions was partially reinstated and parties negotiating pay and conditions had to act in "good faith".

National then swung the pendulum back towards business by curtailing employee rights to rest and meal breaks and introducing "fire-at-will", 90-day trials for employees. National did, however, eventually ban zero-hour contracts. In 2018, Labour downsized the 90-day trials, limiting them to businesses with 19 or fewer employees, and restored rest and meal breaks.

Other changes to labour relations, work conditions and pay are being implemented or are in the pipeline. They include higher minimum wages (the next increase is on Thursday), more sick leave, "fair pay" agreements and domestic violence leave.

However, despite all the cutting and pasting of the past three decades, the basic framework of New Zealand’s labour relations is unchanged. The ECA is still at the heart of it all.

And the ECA has been a failure. Because it was an important component of an ideology that failed to do what it promised.

"That was the final step in the deregulation started by Labour in 1984," Prof Anderson says.

"It was based on the mysterious belief that, if you deregulated everything, the markets would provide.

"But that system, as we have seen, has led to a massive consolidation of wealth at the top end."

"New Zealand workers have never recovered from the introduction of Employment Contracts Act," the president of the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions says.

"The idea was that it would be good for business and that it would trickle down to workers. But that certainly didn’t happen. And business didn’t become more efficient or productive.

"I don’t see that it could have benefited the country if overall New Zealand’s productivity slumped and remains slumped and our democratic institutions were weakened.

"It did benefit big business. It did benefit a management culture based on a master-servant relationship."

Those sorts of unbalanced relationships have been notorious in several sectors including dairy farming, bus driving, security work and fast food.

Jamie (surname withheld) works for a Dunedin fast food outlet that is part of a national chain.

She gets $20.02 an hour and is proud her employer promises to keep pay $1.20 an hour above the minimum wage. She does not mention the living wage, a wage based on what is needed to provide the basic necessities of life, which is $22.10. Perhaps she does not know about it.

In her 20s, Jamie is studying and supplementing her student loan with the fast food work. Because zero-hour contracts were banned in 2016, she gets 11 hours of guaranteed work, split over two shifts, each week. She also has the opportunity to pick up extra shifts if they are available and she feels she has the time or needs the money.

The 11 hours puts about $260 a week in her pocket. More than enough for the $146 a week she pays in rent — rent for her bedroom in a six-bedroom flat, that is. It would be a different story is she was trying to pay rent on a house and feed and clothe children.

Fortunately for Jamie, she is studying towards a university degree. Fast food work is unlikely to be her future. Not so, for most of the country’s 11,000-plus, full-time, big brand, fast food outlet workers. The majority are taking home $510-$750 a week. When the median weekly rent in Dunedin is $421, and almost $500 nationwide, fast food workers and others in low-paid employment, whether they are getting $1.20 an hour above the minimum wage or not, are certainly not benefiting from the existing labour relations system, legacy of the ECA.

If New Zealand chose the wrong path 30 years ago, and is still paying the price, how will we fare with an even bigger employment upheaval; one that has already begun?

Technology, climate change, ageing populations — each will create their own disturbance that, combined, will likely make the revolution of the ECA look like a mere ripple.

"I suspect that in the long-term the change will be much bigger than from deregulation," Prof Anderson says.

"It’s going to be a massive problem ... a slow train wreck over time that will affect all of society."

The Productivity Commission’s assessment is that artificial intelligence has already brought its first tranche of change to workplaces and that the next round will kick off in the next 15 to 20 years, Prof Anderson says.

We need to rethink where we are going, he says.

"What laws are needed to cope with what has come and what is coming?

"We need to get away from the notion of employees ... and just think of workers as anyone who has to get off their butt and do work they are contracted to do.

"You have to rethink who is an employer too, of course."

The government, business and unions are jointly trying to figure out that future, through the tripartite Future of Work forum, Wagstaff says.

"There’s a real chance we will see large levels of displacement with the introduction of some technologies in many jobs in the decades ahead."

At the heart of managing that change needs to be a "just transition" for businesses and their workers, he says.

"It’s the sort of thing the ECA prevented because it didn’t allow workers to have a voice in the system."

Retraining , income maintenance and creating new jobs and opportunities all need to be in the mix.

Prof Anderson agrees. He says we need to be thinking about social insurance systems — the wage subsidies of the Covid lockdowns were an example — so that people have financial security even as more people start losing their jobs through no fault of their own.

If we don’t create a transition, people will resist change, Wagstaff predicts.

"And they’ll resist the logic, the reasons, for change. They’ll fight back. They’ll fight back against climate change and other things.

"So, we really need to support people in that change, so that the burden is even and isn’t just on those individuals."

That was not the way it was done in 1991.

"The change processes in the 1990s were brutal, workers were thrown on the scrap heap and the market didn’t care about them; it just looked for the cheapest product.

"That was the tragedy of those times."

There is no reason the same mistakes have to be repeated, Wagstaff says.

"We need to see it coming and act on it.

"That’s what successful businesses and economies do, they adapt. They don’t just go through a boom and bust process without concern for the consequences."

For Brian, that last dairying job was the final straw.

In his late 20s, he is now at university studying history and sociology.

His time on the farm, however, still angers him.

"We were all experienced workers. We all knew what we were doing.

"Why you would choose to rinse out a team like that, when really he could have just kicked back and given us all a little bit of quality of life ...?

"But he just couldn’t find it in him.

"It’s greed, you know."

Although Brian has left the industry for now, it might still count for something.

"After that experience, I’m kind of interested to see if we could reinvigorate unions."

*Not his real name.

Comments

A large amount of one-sided gibberish in here. What the ECA so successfully did was free up the labour market in a way that benefited both employers and employees. Many of the so-called 'low-wage' jobs wouldn't have existed in any form without the ECA. The old union-dominated system may have seemed good for those already in a job but it definitely wasn't so great for those who wanted one.

The income share and income inequality lines on the graph are disingenuous and misleading as they're based on gross income and ignore taxes and transfers such as Working for Families.

Working for families is a government business subsidy and wouldn't be needed if wages had kept pace with productivity etc. In fact if they had then our min wage would be around the living wage . Workers are effectively working longer and harder for less compared to 30 years ago . Not to mention the inflation calculation doesn't accurately reflect housing costs so the actual change is much worse and the workers share of the pie is still dropping.

The elephant in the room is mass immigration which has provided a large pool of (generally low paid) labour ... so the supply side labour availability has depressed workers' value to the economy. When we have people trapped overseas complaining that their work visa, obtained after some qualification from an independent training supplier, is not able to get them back into NZ for their job as a petrol station forecourt attendant we should see the problem.

The graph provided has some pretty lines - notable is that the Gini statistic seems to be rising steeply before the 1991 Act came into force.

With automation more is invested in capital,and less in labour ... but most NZ employment is in service industries. Production became automated from the late 1950s when local diary factories were replaced by whole milk collection. Freezing works followed in the 1970s-80s. With price depression farms became smarter, requiring less labour.

This article could have been so much more informative and useful.